Best Video Film & Cultural Center | Arts & Culture | Film & Video

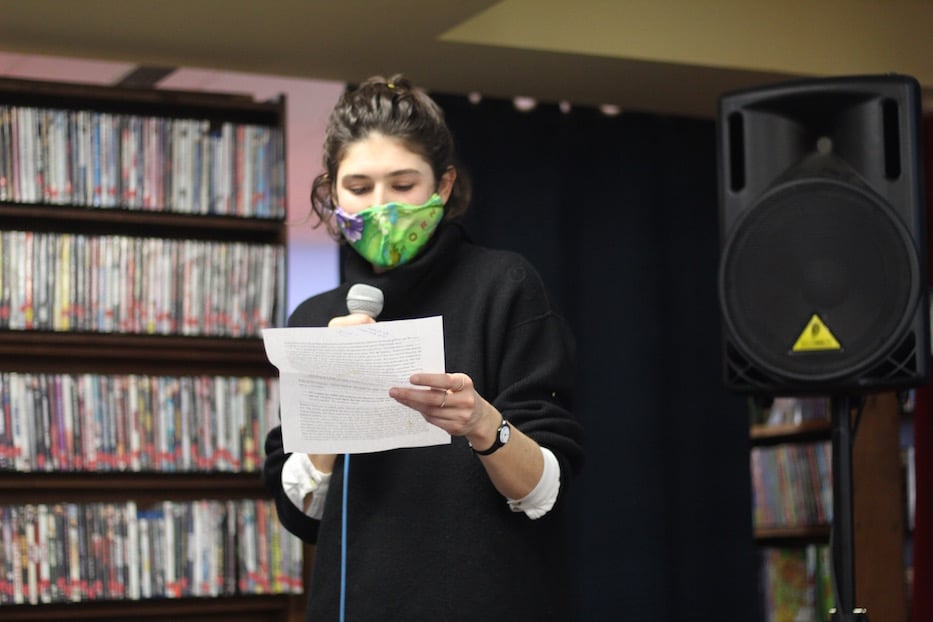

Raizine (Rai) Bruton and Jules Larson. “Portrait of a Cinema on Fire: Feminist Filmmakers” continues March 15 with Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Marianne and Héloïse are watching, their eyes fixed on the mattress. There, Sophie lies flat on her back, her eyes to the ceiling. In front of her, a midwife takes a salve—pennyroyal, or meadow rue, or maybe something else entirely—and packs it beneath her nightgown and between her legs. The camera comes in close, intimate on Sophie’s grimacing face. That’s when a viewer sees it: the infant looking at Sophie, playing absentmindedly with her long, tensed fingers. A fire, crackling in the background, is the loudest voice in the room.

They are all looking: at each other, at themselves, at their multiple futures and their past lives. They are looking even when they are not looking at all.

Céline Sciamma’s Portrait Of A Lady on Fire (Portrait de la jeune fille en feu) transported a small audience Tuesday night, as it arrived at Best Video Film and Cultural Center as the first installment in “Portrait of a Cinema on Fire: Feminist Filmmakers.” The festival, which marks a first for the nonprofit, is organized by employees Jules Larson and Raizine Bruton. Larson is a multimedia artist and writer; Bruton is an aspiring filmmaker and self-described cinephile.

The festival continues March 15 with Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground and returns March 22 with Bette Gordon’s Variety. In April, Best Video will follow it with a multi-week screening series on music. It is supported by a grant from CT Humanities; all screenings take place at Best Video's 1842 Whitney Ave. home in Hamden.

“A lot of these movies that people have never even heard of are movies that we’ve had on the shelves for forever, and this is a time that we can screen them,” Larson said before the film. “It’s not just milquetoast, feminist, like, ‘We’re gonna talk about gender for two hours.’ This is real content, real feelings, and what happens when a woman is not only directing, but writing and storifying something that really needs to be said in a cinematic way.”

The festival started with a mutual love for movies and for Best Video, where DVDs fill the wall-to-wall bookshelves in neatly labeled sections. Months ago, Larson and Bruton noticed that films they thought of as feminist canon—Cheryl Dunye’s 1997 Watermelon Woman, for instance, or Claire Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum—received little more than a passing nod from patrons.

Both started thinking about curating a small collection of movies as a sort of primer, similar to the Criterion Collection’s virtual shelf of women filmmakers. The two share a love for films directed, written and acted by women. Bruton can wax poetic on the role director Chantal Akerman has played in her own life. Larson can jump from Norma Shearer’s work in 20th century Hollywood to why Zora Neale Hurston has been overlooked in both film and literature. A small festival, with a longer one somewhere down the line, felt right.

“We’ve been thinking and trying to find films and doing all that” for close to a year, said Bruton Tuesday. When the two started mapping out a short festival, she helped Larson narrow her list from “like 400 movies I [Larson] wanted to screen” to just three. The choices from Sciamma, Collins and Gordon are meant to represent a jumping off point, rather than a conclusive chapter in feminist film history.

Leana Hirschfeld-Kroen introduces the film.

Written and directed by Sciamma in 2019, Portrait Of A Lady on Fire follows Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter poised to inherit her father’s portrait business, as she travels to a remote part of Brittany, France on commission to paint Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) for her wedding portrait. The year is 1770—just 19 years before the French Revolution, when France’s own ripe-breasted, flag-wielding heroine of the same name was popularized by a man.

When she arrives, Marianne learns from Héloïse’s mother (Valeria Golino) and the family’s servant Sophie (Luàna Bajrami) that her task may not be as straightforward as she once thought. Héloïse cannot know, at least at first, that she is being painted. She’s already run off one artist, who left without completing her face. Marianne will pose as her companion and chaperone, stealing glances at her when she can. What ensues is a kind of adult cache-cache that is as mental as it is literal, as much about silence as it is about what is spoken.

Sciamma is closely attuned to the nonverbal communication between them; she reminds her viewers that looking can be a fully sensory act, and also one devoid of tenderness and feeling. The film made history when it became the first film directed by a woman to win the Queer Palm at the Cannes Film Festval, where it also took best screenplay.

"I think French films and women filmmakers were two of the first ways I understood how I could self-construct around seriously engaging with film,” said Leana Hirschfeld-Kroen, a lecturer in film studies at Yale who introduced the film, in a conversation with Larson and Bruton beforehand. "I really love how much the films you've chosen are not only films by women filmmakers, but are about gendered labor more broadly, feature artists as leads.”

Tuesday—International Women’s Day, although Larson said the date was a happy coincidence—a small audience gathered inside the Whitney Avenue space as the temperature continued to plummet outside. Standing before the projection screen, Hirschfeld-Kroen encouraged attendees to watch carefully for Sciamma’s sharp eye—itself a looking glass that is never explicitly mentioned, but through which everything is filtered. She pointed to edits that move, with equal parts economy and grace, from one type of work to another—like when a hand grasping charcoal becomes one that is doing embroidery, or chopping vegetables at a long, shared table.

As the lights went down, viewers sank into the filmmaker’s rich portrait of two (and sometimes three) women unmoored and yet perfectly centered, their own eyes wide so as not to miss a single detail. They watched as Marianne stole glances at Héloïse, her face partially covered as the salty tide came crashing in. They watched as Sciamma, through a trick of the eye, turned flesh, hair, and fingers into familiar and foreign territory. They listened as silence thrummed and pounded through whole sections of the work, stunned when voices punctured it with an incantation that seemed other worldly.

In an interview after the film, both Larson and Bruton stressed the significance of screening films that can act as both windows and mirrors, opening viewers’ worlds while also reflecting something of them back to them. Born and raised in New Haven, Bruton grew up “in a household where it was mostly women,” including her mother, her grandmother, and her sister.

Her favorite parts of the film follow Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie as they grow closer in the absence of domineering matriarch, blurring the lines between sisters-in-spirit, lovers, and simply each other’s to protect in whatever way they can. There are references, for instance, to menstrual cramps and unplanned pregnancies—still sometimes a filmic taboo hundreds of years later. In the end, the three make viewers question what they know of their own freedom, and that of the women around them.

Larson said that’s part of the hope behind the festival. The first time she saw Portrait in early 2020, she let the credits run and then immediately started the film from the beginning again. There were worlds to unpack, she said; there always are at the end. She’s seen it five or six times since, and always finds something newly revelatory.

"Understanding the content is fine, from like No Country for Old Men or something like that, but then like, feeling the content and feeling yourself like, seen in another film—it's so disorienting when you don't have that as an immediate valve,” Larson said. “You have to look for that, you find it, and it's so relieving."

“Portrait of a Cinema on Fire: Feminist Filmmakers” continues March 15 with Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground. For more information, visit Best Video Film and Cultural Center’s website.