Creative Arts Workshop | Visual Arts | Arts, Culture & Community

| Lucy McClure: "When somebody is fleeing their country because of crime and because of genocide, sanctuary seems like a human right." Lucy Gellman Photo. |

New Haven isn't officially a sanctuary city yet. But a group of artists is joining longtime immigrant rights organizers in hopes of helping it become one.

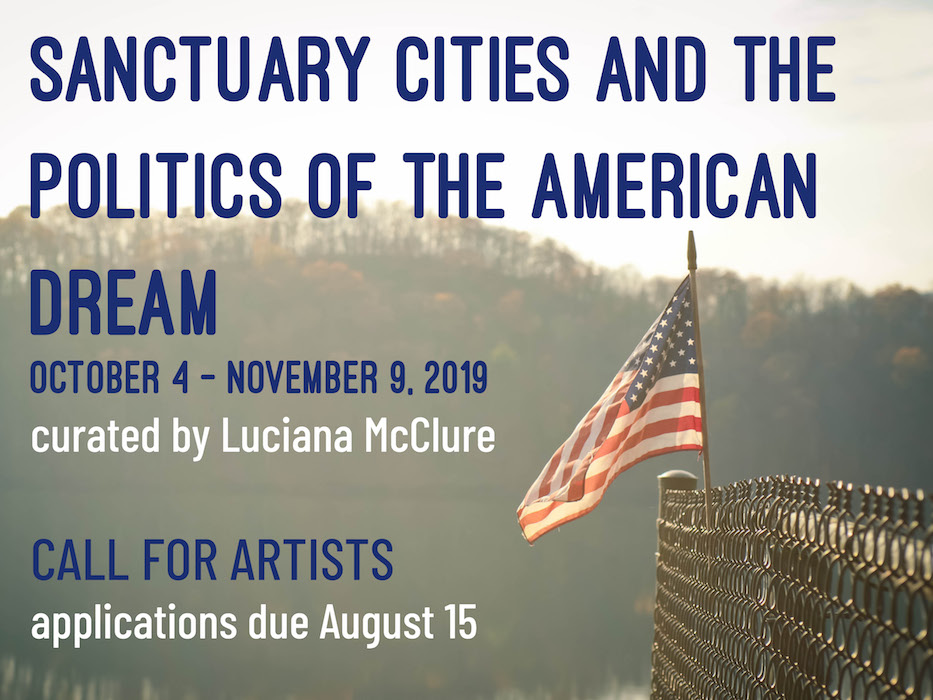

That’s the overarching goal—one of many—for Sanctuary Cities and the Politics of the American Dream, an upcoming exhibition at Creative Arts Workshop (CAW) that recently launched a nationwide open call for artwork exploring migration and immigration, citizenship status, sanctuary, land sovereignty and citizenship.

Submissions are accepted through August 15; the show opens October 4 and runs through Nov. 9, following the city's Nov. 5 mayoral election.

The exhibition, which is partially funded by a $20,000 grant from the International Association of New Haven, is being curated by Nasty Women Connecticut Co-Founder Luciana McClure, herself an artist and Brazilian immigrant who arrived in the United States in 1999. She said she was moved to apply for the role because “when somebody is fleeing their country because of crime and because of genocide, sanctuary seems like a human right.“

In addition to inviting national and international names like JR, a French artist who has installed a huge photo of a toddler at a border fence in Tecate, Mexico, McClure said she is working with local artists-activists Vanesa Suarez, who is at Unidad Latina en Acción and Ana María Rivera Forastieri, who is at the Connecticut Bail Fund, to build momentum around official sanctuary legislation from the city’s mayor and Board of Alders. She is also hoping that the exhibition will bring more attention to Nelson Pinos, an immigrant who has been seeking sanctuary from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement officials at First & Summerfield Church for almost two years.

She said that while she’s leading as a curator, she is largely taking cues from leaders in the immigrant community, who have been rallying around the issue for years. That includes Fatima Rojas, a founding member of ULA and one of the most vocal proponents of official sanctuary legislation in the city.

As submissions begin to flow in, The Arts Paper sat down with McClure to discuss the role of artists as activists and instigators, the difference between symbolic and legal sanctuary status, and how New Haveners can get involved in both the city’s fight for sanctuary and a humanitarian crisis unfolding at the U.S.-Mexico border. That interview is below.

So let’s just get into it. All of it. And let’s start with what’s happening right now.

I just feel like I can’t sometimes. I have a really hard time reading the news, I have a hard time seeing the stories, the faces. Reading about the situation [that’s happening right now at the border] … it’s not that far for me. I feel connected as an immigrant, and also as a mother.

Even though my immigrant story and experience is different from others, we all came here because we wanted a better life. Whether it was for a career, whether it was for a fellowship, whether it was for asylum, for whatever reason—it was because of that promise of the “American Dream.” Of a better life, of this first world nation.

In this country, we have vast amounts of land. We have jobs that are not being utilized. Maybe we need to think about the way that we are building our community. The way we’re providing jobs. There’s so much that we could be doing. To throw somebody away because you think that that’s the law is like ... it's the same thing as saying “well, religion says.” People are using words because they don’t want to be associated.

When we turn away, it’s on all of us. It’s on all of us. I’m angry and surprised that more people aren’t angry.

In what ways have you experienced that in your own life?

Well, when I moved here, I didn’t speak any English. I had many people treating me poorly because I couldn’t speak the language. You know, people speaking loud to me. People asking all sorts of absurd questions about Brazil. Like, if we had T.V., if we had cars.

And to me, it was just like, what? How much do we even really know and understand of other countries, other nations, other races, other religions? I think, like, there isn’t enough of an understanding, but there is a lot of assumptions and a lot of stereotypes.

Right now, I think about my own family. We moved here because my parents wanted a better life for me and my sisters. They could have had much better careers if they’d stayed in Brazil. And I think, for every immigrant that is coming here, they have that idea.

But the way we came, there’s also a sense of privilege. And I think I am privileged in many ways, compared to some of my immigrant brothers and sisters. Because the truth is, I am seen a lot more often as white than Latinx. And how do I use that to support them as I come to terms with my own immigrant experience and my own sense of self and identity?

Can we back up for a second? You mentioned the number of people who assume you are white, and not Latinx. What is that doing to you, internally?

Yes! It makes me wonder about myself, and ask how honest I’ve been with my own identity. Because I definitely pushed away that part of myself for years. Moving into the United States, you’re trying to assimilate into this new country, and you’re already struggling with your own sense of self.

When I first moved, people had a hard time saying my first name, and my last name [Quagliato]. For my entire high school and college experience, I was called Lucy Q only. So I was completely reduced. And that made it easier.

You’re trying to fit in, and you’re trying to remove a certain part of yourself, and then all of a sudden everything becomes a lot easier because you’re not claiming so much of your heritage. And it’s a problem. I didn’t realize how hard it was to claim this part of myself until I became a parent, and realized that it was so important for me to raise them bilingual, to have passports, to go to Brazil. When we deny parts of what we are, we can’t deny it forever.

It also makes me want to elevate the voices in the true immigrants in our community, that are at the forefront of the immigrant fight.

Tell me more about how you're implementing that approach. I know you mentioned working with Vanesa and the folks at ULA.

To me, I just feel that if I’m going to do a call about Sanctuary Cities and the Politics of the American Dream, I can’t be true to that, to the actual goal, unless I directly work with people that are on the forefront of these issues. That really understand what’s going on. They can educate me, and they can talk to me, and they can say, “this is how you can help.”

I think that’s what it means, being an ally. It’s understanding that you don’t have the answers. That you want to help, but you need to be able to learn. You need to be able to listen. You need to be able to let them guide you and tell you how you can best serve as an ally.

What have those discussions been like? I know it’s still very early!

I had one or two of them, and it was very emotional. It involved me talking about myself as an immigrant, which I haven’t talked about at all, and realizing how difficult that is. But also finding that it is one of the reasons why I have this opportunity in the community to curate this show.

I feel very happy that CAW understands that they can’t have an exhibition about that without having an immigrant curate. Without having someone that actually experienced that.

I want to talk about both immediate and long-term vision for this show. What are you hoping for as you and CAW open this call for artists?

The exhibition—I felt like it was a calling. I had stepped into this path, which was not planned, with Nasty Women. I was just an artist, I had never curated exhibitions, I had never been embedded in the community. This is a continuation on that path.

It won’t be about just seeing things and being comfortable, but how the arts really do have a duty to be political and create discourse. I want people to explore themes of identity, belonging, home, dislocation, human rights and morality.

I am currently reaching out to specific immigrant artists, because I am interested in having the immigrant voice be a big part of this. As it is a national call, I’m hoping to be in touch with artists in California, in Arizona, in New York—hoping that it will spark something in those other states as well.

But also, there are artists that are not immigrants, or maybe they’re immigrants from many layers. Maybe they’re first generation. Maybe their parents have stories. Maybe they grapple with their own identity because they are first generation. I want people to explore their ideas with this, and see how they are translating it through their writing, through film, through music.

And hopefully, the goal by the end of the exhibition is to bring enough national focus into New Haven that we can really, truly be a real sanctuary city.

That’s the other part of it that I wanted to ask. This legislative piece.

I think we need more conversations around what a sanctuary city is and why it is important. Why are we not a true sanctuary in New Haven? If we currently have somebody that cannot walk out of a church, we’re not a true sanctuary. If it [the city] was, Nelson would be free to walk away. How, as a community, are we protecting people that are here, that are not criminals?

This person [Nelson] is a father. Who came here, who worked hard for that dream, who sought a better life. Who just wants people to open his case and truly take a look. The fact that we’re not even willing to give him a chance—I think that’s wrong. Everything he’s done in his life, it’s like everything never happened if he gets sent back.

That’s what I think about when we talk about morality, when we talk about community, about what we can do.

Who is the “we”?

Artists! There are many artists already grappling with the immigrant crisis, but I want to see more of them in our community. I want to see people coming together as they really dissect this theme, and think about sanctuary cities and the American dream. They are more intertwined and they are more similar as an ideology than a reality.

I think it’s safe to say that Creative Arts Workshop has historically been a very white space.

Yes.

And so is part of this not just engaging white people in dialogue, but also asking white artists to step up by making space for other people?

That’s the work! Liberals, we have all bought into the movement already. I know that the entire Nasty Women Connecticut community, I know they’ll all be submitting. I know all the allies, all the organizations I’ve been working with, I’m not worried about them.

But it’s like, how are we engaging those that are not aware of all this? How are we getting the white community to all of a sudden realize that … to think about what it means to be a community member?

It’s also about asking: Where are you putting your money? Who are you supporting? We’ve been talking recently about the Wayfair workers (who walked out after learning that the company was supplying beds to migrant detention camps) … do your homework. Understand where your money is going.

Nobody is telling you to give thousands and thousands. If you can, wonderful. Do it. But also think about the Connecticut Bail Fund. Think about ULA. Think about JUNTA. Think about CIRA (the Connecticut Immigrant Rights Alliance). Think about organizations that are on the forefront, doing everything in their power—not because it is a commodity, but because there is no other option.

What are some of the bigger picture messages you want to get out into the community with this project?

Well, I’ve seen people looking around and saying: “What can I do? What can I do?” Well, start in your community! You cannot expect to change the world if you’re letting the community around you fall apart. We have immigrants here. So start here.

There is always some sort of violence that’s happening toward a certain group of people. Historically, that has always existed. And so I feel that’s a part of our human condition to feel desensitized or to feel that it’s part of history—that this is how it goes. Until it’s about your own group, I think many people don’t see that it is about them. That it feels close.

The fact that people are like “yeah! We’re totally a sanctuary city!” We are not. We are not! Or Nelson wouldn’t be in church. There are people that don’t even know Nelson’s in sanctuary! And for me, it’s like—how is it that we don’t know?

How are we protecting our neighbors? How am I supposed to feel safe, how are you supposed to feel safe, when our own neighbors don’t have our own back as people? But you know what? If they’re not coming after you or me, they’re going to come after somebody that you know! And we’re all related to somebody that is being affected by this.

As a woman, as an immigrant, as a mother, I cannot fathom not doing anything about that. So if that means changing legislation in my community, I’m gonna do it.

For more information on Sanctuary Cities and the Politics of the American Dream, click here.