Fair Haven | Arts & Culture | Movimiento Cultural Afro-Continental | COVID-19

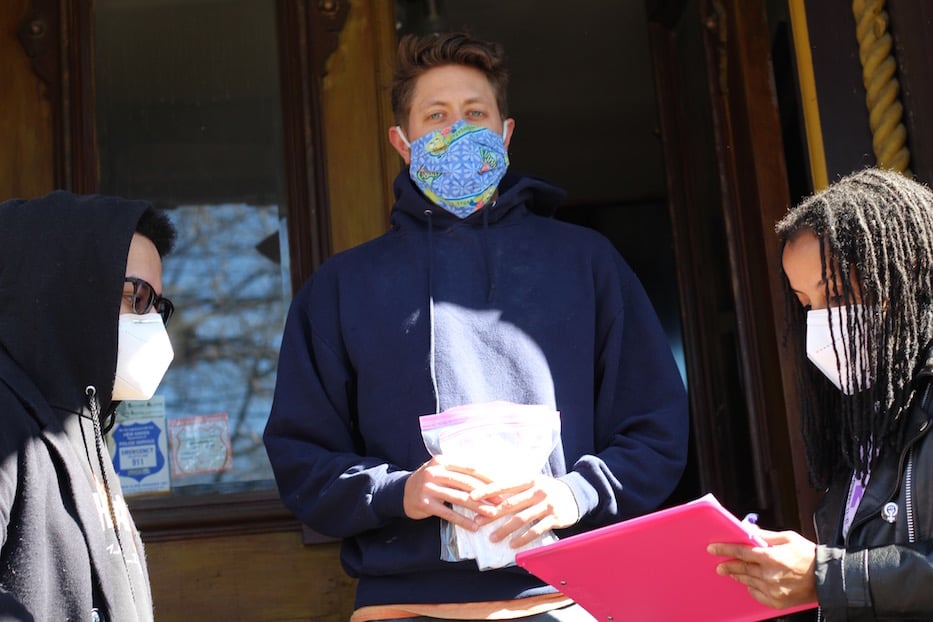

Henry Fernandez, Jr., Kica Matos, Tanya and William Redd. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When Tanya Redd heard her neighbors from down the street knocking outside, she came to the door. When they had information on how to get her 83-year-old mother-in-law vaccinated, she opened her door a little wider.

Redd lives in Fair Haven, one of the neighborhoods that has been hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic in both the city and the state. Saturday, her house became part of Vaccinate/Vacúnate Fair Haven!, a new grassroots campaign that pairs old-school canvassing with public health outreach to get the neighborhood vaccinated.

The campaign is a collaboration among Fair Haveners Kica Matos, David Weinreb, and Karen DuBois-Walton and Fair Haven Community Health Care (FHCHC), with community partners that include Clifford Beers, Unidad Latina en Acción, and the Fair Haven Community Management Team among many others. In two weeks, organizers have built a roster of almost 300 volunteers, who hit the pavement starting Saturday afternoon. The campaign, which encompasses 5,648 homes over a 70 block radius, is scheduled to continue through the spring.

As of Saturday evening, volunteers had scheduled 59 new vaccination appointments for interested and eligible neighborhood residents. They'd spoken with an additional 29 residents who were hesitant or unsure about the vaccine, 64 residents who had already been vaccinated, and 51 residents who are interested but not yet eligible to get vaccinated.

Matos said that the goal is to vaccinate all 17,141 residents of the Fair Haven, 83 percent of whom are people of color, many of whom are undocumented, and many of whom are essential workers. While she and FHCHC Chief Executive Officer Dr. Suzanne Lagarde spent the week asking the Lamont Administration to lift their age-based vaccination formula for a neighborhood pilot program, they have not yet had any luck.

“These workers have helped lead us through this pandemic,” Matos said Saturday, switching between English and Spanish as she spoke during a kickoff at FHCHC’s Grand Avenue headquarters. “As grocery employees, as people who clean our buildings, work in our factories, and tend to our disabled brothers and sisters. Just yesterday, Governor Lamont admitted that the state has failed Black and Brown communities miserably when it comes to Covid vaccinations. We have a plan to fix that, and that is why we are here.”

“With love, and with determination, let us dedicate ourselves to the task at hand," Matos said.

“With love, and with determination, let us dedicate ourselves to the task at hand," she continued. "Let us get our neighbors vaccinated. Let this beautiful coalition—look around you!—let this beautiful coalition of residents, allies, public officials, community leaders, and generous volunteers come together to wrap our arms around our beloved community and to drive this horrible virus out of our neighborhood.”

All of them come at the campaign from a different background, united by a fierce love of the neighborhood they call home. Matos is a longtime community organizer and champion of immigrant rights. Weinreb, whose introduction to the neighborhood was teaching English to newcomers at the Fair Haven School, is on the board of the Fair Haven Community Management Team, and lives not far from FHCHC on Perkins Street. DuBois-Walton is a longtime Fair Havener and head of Elm City Communities, the city’s housing authority.

Launching The Campaign

David Weinreb, one of the organizers of the campaign.

For two weeks, organizers have been working closely with Fair Haven Community Health Care to streamline canvassing efforts and recruit volunteers both within and beyond Fair Haven. The technology that the campaign is using is relatively simple: volunteers knock on doors, help residents sign up on the spot, and leave literature in English and Spanish if people aren’t home.

Volunteers also find out whether people need transportation to Wilbur Cross High School, where FHCHC runs a large-scale vaccination clinic. Prior to Saturday’s kickoff, Weinreb and Matos coordinated a series of bilingual volunteer orientations on Zoom, to walk volunteers through canvassing and dispel common misconceptions around the vaccine.

“If one of our neighbors decides not to vaccinate, we do not want it to be for a lack of access or information,” Weinreb said. “We will not let it be for a lack of access or information. Today, together, we will provide access to all of Fair Haven.”

Top: Marlene Edelstein signs volunteers in. Bottom: Magalys Perez and Matthew Weinreb.

Saturday, the center’s Grand Avenue headquarters bustled with activity. Volunteers cycled through tables stacked with clipboards and Vaccinate Fair Haven flyers, colorful t-shirts, individually bagged surgical masks and doll-sized bottles of hand sanitizer. Magalys Perez, a nurse who works at Fair Haven Community Health Center, arrived with her two children ready to pound the pavement.

As a healthcare provider who works in the community every day, she said she feels like she has a stake in the ease and access with which Fair Haveners are able to get vaccinated. Her kids, Sophie and Eli Green-Perez, came to experience and participate in the action.

“We wanted to be a part of this,” she said. “We’re trying to get the word out to the community.”

Rachel Schwartz fills up on extra masks and hand sanitizer to distribute.

Others came to support the community because it is their personal or professional home. Sophie Tworkowski, who lives in Hamden, has taught English as a Second Language (ESL) courses at JUNTA for Progressive Action for a decade. She heard about the campaign through Weinreb, who helped her move her classes to Zoom classes at the beginning of the pandemic.

Her daughter Rachel Schwartz, who works as a nurse in New York City, came up for the day to canvass. Schwartz also speaks Spanish, and thought her skills might come in handy. She said she was excited to spend the day not only doing public health outreach, but also hanging out with her mom.

Speaking in a mix of English and Spanish, Fair Havener Norma DeLeon said that she had signed up after seeing a notice on social media. While she is not yet eligible for the vaccine, she said she’s excited to get the word out—because she sees a vaccinated Fair Haven as a safer place for her family. As a mom of five, she said she sees it as a way to take care of her kids and herself.

Top: Norma DeLeon. Bottom: Stephanie Quainoo.

Top: Norma DeLeon. Bottom: Stephanie Quainoo.

Stephanie Quainoo, a second-year medical student at Quinnipiac University, came out “because I’m part of the community, and it’s part of my job to provide vaccine equity.” As a healthcare provider in training, she said that she’s constantly aware of the way the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated wide gaps in the healthcare system that existed long before the virus arrived in the United States a year ago.

“We need to be proactive and bring information to the community,” she said.

Lagarde, who buzzed around the space to field questions, give interviews, and prepare volunteers, said that she is energized by the campaign but frustrated at the state’s age-based vaccination formula, which does not currently make exceptions for essential, frontline workers and those who are immunosuppressed.

Earlier this week, a federal complaint from Connecticut Legal Services, Inc., the New Haven Legal Assistance Association and Greater Hartford Legal Aid alleged that the current plan is inherently discriminatory. The state has not yet made any changes to the rollout.

If it does not do so, “we’re going to have to do this many times,” Lagarde said.

“Where Morality And Science Come Together”

In a press conference before volunteers set off, a mix of grassroots organizers, elected officials and artists-activists pumped up the crowd, leaving them dancing in the parking lot before hitting the streets. Almost all who spoke reflected on the one-year anniversary of the pandemic, which has killed over 500,000 Americans, left millions of Americans unemployed and without health insurance, and driven almost 3 million women out of the American workforce.

All of those figures are amplified in Fair Haven, where the virus has ravaged a community of essential workers, undocumented immigrants, and close-knit families, where multiple generations may live under one roof.

John Lugo: We're suffering.

John Lugo, co-founder and director of Unidad Latina en Acción, said he would be knocking in honor of Nora Garcia, a Fair Haven resident who died of Covid-19 last month. Garcia was an essential worker, tasked with cleaning at Yale New Haven Hospital. Because she worked on contract through a company, Lugo said she was unable to get a vaccine.

“And we feel that’s a crime,” he said. “And I feel that’s a crime, that when the governor is refusing to provide the vaccine for essential workers—and we are essential workers! And we’re suffering. Our people are essential workers. We work in construction. We work cleaning. We work on the farms. And we still, we’re not getting what we deserve.”

“I talk often of the grief gap. Not the statistics, but the grief gap in our communities. And that’s real.”

Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, associate dean for health equity and research and an associate professor at the Yale School of Medicine who was tapped as the chair of the White House’s Covid-19 health equity task force earlier this year, praised the campaign for its effort to make Connecticut’s rollout more equitable for all of the state’s residents.

“I know that we’ve had a year of deep sorrow and grief and suffering that has been disproportionate,” she said. “I talk often of the grief gap. Not the statistics, but the grief gap in our communities. And that’s real.”

She reminded volunteers that there are currently three approved vaccines. She spoke about President Joe Biden’s promise, delivered earlier this week, that all Americans would be eligible for vaccines on May 1. Then she gave volunteers their marching orders.

“Vaccination is absolutely going to be vital for everyone,” she said. “And this is where morality and science come together well. We need every community to be able to connect with vaccines. It needs to be easy, it needs to be convenient, and free. And that’s what you’re doing today. It is equity in action, and I thank you so much for that.”

Before Movimiento Cultural Afro-Continental got volunteers moving with Puerto Rican bomba, DuBois-Walton sent the group off with one final push. As she looked around at a sea of almost 300 volunteers, she vowed that “we are going to do this together.” She added that she does not just want to see the effort stop at Fair Haven: she envisions it expanding across the city.

“This is what equity looks like,” she said. “Equity looks like seeing a challenge where there was a community that was underserved, and thinking creatively about how we were going to not sit back and just say, ‘too bad that we can’t get our residents vaccinated.’ But we’re gonna come up with plans that are gonna do that, that are going to make it accessible to every household, because we are committed to knocking on every single door.

"We are committed to making sure that there is vaccine for every single household. And we are committed to making sure that transportation will not be a barrier to that.”

Pounding The Pavement

Back at their kitchen table on East Pearl Street, Matos and her son Henry Fernandez, Jr. strategized before hitting the sun-soaked block. The two set up a system with papers stacked neatly on one clipboard, and a blank, gridded sheet for data on the other. Fernandez, a sophomore at Engineering and Science University Magnet School, said that he had decided at the last minute to join his mom because he cares about the Fair Haven community.

The block is also close to Matos’ heart: she and her husband, LEAP Director Henry Fernandez, moved in two years before their son was born. DuBois-Walton lives just down the street, in the house where she and her husband raised their two sons. As they double checked supplies—extra masks, hand sanitizer, little cards from FHCHC—their dog Logan padded over and nuzzled, as if to give a non-verbal nod of approval for their work.

Top: No dice, in which case volunteers leave literature. Bottom: Allison Ostriker.

Back out on the sidewalk, the first few doors went unanswered. After the first neighbor to respond gave her a hard no, Matos seemed crestfallen. Then Allison Ostriker swung her door open, a handle turning dramatically against its heavy blue frame. A toddler tiptoed behind her, switching from leg to leg as she looked out at the new people on the porch.

Matos began with a simple introduction: she and Henry were the neighbors from down the street, in the light blue house. Was Ostriker interested in vaccination? When Ostriker answered with a yes, Matos started taking down her information. She later said she is excited to get vaccinated because she has a doctorate in pharmacology, and trusts the science. At 41, she’s still waiting to become eligible.

Ostriker turned out to be the first of many neighbors, almost all of whom must wait because they are not yet eligible for vaccination. One neighbor, speaking in Spanish, said she would love to find out more about the vaccine and was grateful for the extra masks. When neighbor Louie Krak opened the door, he did a little jump for joy and invited the two into his foyer. As Matos scribbled down information, he spoke animatedly through a mask festooned with characters from the Spongebob Squarepants cartoon.

Louie Krak: Ready.

As a graduate student and teaching assistant in environmental studies at Southern Connecticut State University, “I was told I was on some list,” and then found out he was not yet eligible for a vaccine. He said he also worries about his girlfriend, who works in the service industry and interacts face-to-face with people as part of her job.

A few houses in, Fernandez had turned into a canvassing natural, often the first to bound up the steps, locate the doorbell, and add a knock for good measure. At one house, he paused after spotting a black scarf tied around the doorknob, flapping in the wind beside a tiny Puerto Rican flag. At another, a neighbor came to the door, breaking into a huge grin with the news that he’d already been vaccinated, but loved what the two were doing.

Other neighbors were more skeptical, but took Matos up on the offer to continue the conversation, or sign up family members who were eligible.

Redd, who lives with her husband William, her daughter, and her mother-in-law, said she isn’t planning on getting a Covid-19 vaccine. She wants to get one for her 83-year-old mother in law, who has difficulties getting around and is living with the family for the moment. William chose to get vaccinated a few weeks ago.

“I believe in God,” Redd said when asked why she doesn’t plan on getting the vaccine. “I believe he protects and keeps his people. I wear masks, because you're not on this earth by yourself. But I haven’t had it—thank you Jesus.”

Just down the street, Housatonic Community College professor Jennifer Jensen welcomed the campaign, noting that she can’t wait to be vaccinated. Jensen is what’s known as a Covid-19 “long hauler:” she had the virus a full 12 months ago and is still experiencing symptoms.

Jennifer Jensen is still experiencing symptoms a year after first battling Covid-19.

Leaning on her railing for support, she detailed a litany of including tremors, fatigue, headaches, a sense of smell that “comes and goes,” and difficulty remaining vertical for extended periods of time.

Listening intently, Matos wrote down her information, and then pointed to her house at the end of the street. She was there if Jensen needed to check in, she said.

“It’s amazing,” she said as she and Fernandez continued on to the next house. “I’ve gotten to know neighbors I didn’t know before.”

To get vaccinated at the Wilbur Cross site, people who are eligible can make an appointment by calling 203-871-4179 or by emailing info@fhchc.org with their name, date of birth, address, and phone number. The process is free and open to people regardless of insurance or documentation status.