Bridgeport | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | City Lights Gallery

| Detail, The Explorations of Professor Bitz. The piece is included in artist Scott Schuldt's The Re-Education of Smedley Butler and Other Stories, running at Bridgeport’s City Lights Gallery through April 6. Lucy Gellman Photos, all work by Scott Schuldt. |

At first glance, we can’t tell that it’s the arctic circle on the anorak. Tiny blue beads spread out around the shoulders, right at that spot where one’s neck melts into the collarbone. There are pink circles and strips rimmed with red, jagged at the sides. A fringe of green pops in and out, with more pink spreading at the shoulder caps.

Then the arctic topography becomes familiar, and a terrible clarity sets in. This resource is melting even as we look. On the anorak, animals tumble from the circle, sailing towards a tangle of flames below. In our world, even the gallery seems to heat up a little bit.

| Detail, The Explorations of Professor Bitz. |

That gnawing sense of precarity underscores Scott Schuldt’s The Re-Education of Smedley Butler and Other Stories, running at Bridgeport’s City Lights Gallery through April 6. A collection of Schuldt’s drawing and intricate beadwork, the show takes a striking and often reverent look at the world around us, reminding viewers exactly how much is at stake if we keep chugging manically forward at the same speed.

The Re-Education of Smedley Butler begins and ends with the two same things: Schuldt’s hands, which have guided him out of a career in engineering and into one in drafting and beadwork. Born and raised in Minnesota, Schuldt worked as an engineer for Boeing for 20 years, his hands speaking systems and mechanics until the summer of 2005. During that time he was based in Seattle, learning about the area’s rich natural resources and Native history when he wasn’t working.

Even before he left Boeing, Schuldt started teaching himself beadwork by looking at Native American art. When he left his job in 2005, he dedicated himself to the craft full time, holding exhibitions and residencies on both coasts before moving to Milford with his wife in 2012. While the work is meticulous, he said it comes together intuitively—he doesn’t always know the next step until he’s finished a first or second phase of the project.

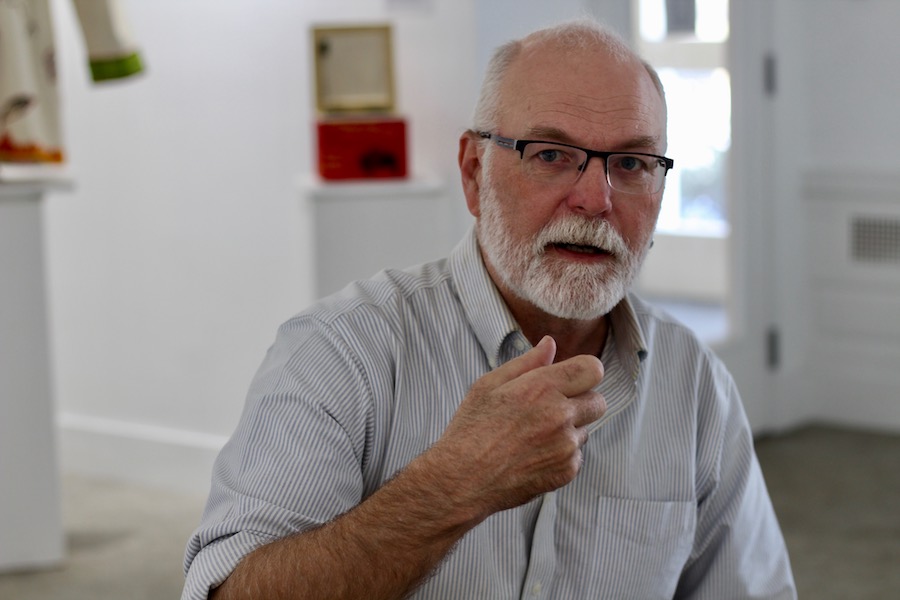

| Artist Scott Schuldt: “I’m trying to do work that makes people think about the issues. I just want them to think.” |

“This is about telling stories,” he said on a recent tour of the exhibition. “I’m trying to do work that makes people think about the issues. I just want them to think.”

In the exhibition, his attachment to both the form and to the world around him comes across immediately. On one of the first walls, Notes From Smoke Farm (2012) springs to life as not just a beaded self-portrait, but a document of Washington’s fraught history with natural resources. In the piece, based on Schuldt’s year as the first artist in residence at Smoke Farm, the artist leans on a stick, looking out at the viewer.

He is dwarfed by the environment around him, a fact that he doesn't seem to mind at all. His face looks out from a thick brown sunhat, a mix of red and white flannel below. Around him are the towering ghosts of trees—redwoods that have been chopped for lumber, and the second growth cedars that are coming back. The longer we look, the more we see in this habitat: lush greens and thick forestry that Schuldt spent much of his time navigating. The “forest matriarchs,” as he refers to them in an accompanying note.

| Detail, Notes From Smoke Farm (2012). The piece, which documents Schuldt's year as the first artist-in-residence at Smoke Farm in Washington state, is 30 x 53 inches of hand-sewn bead work. |

Along sides of the canvas in delicate white beading, Schuldt has woven something called the timber cruising formula, a way to create a kind of forest inventory. But it is crossed out, taking a backseat to a map of the Stillaguamish River that runs through the forest. Here—they are his notes, if we are to glean anything from the title—he stakes his claim: taking a resource’s inventory is a foolish thing to do, because it doesn’t have a quantifiable value. Not one on which anybody can put a price, at least.

There’s nothing gimmicky in this reverence for natural systems, which winds through the show not unlike the rivers, canoe trips, and hikes that have inspired the artist. In Salmon/Cedar Forest Overview Plan (2014), Schuldt has included careful nods to the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest, integrating Raven and Dzunuḵ̓wa into the work as he depicts the interconnectedness of the migrating fish, the water in which they swim, and the surrounding forest.

It’s clear that he’s aware he—and all of us—are on land that was never ours, and he wants us to chew on it for a while. Standing by the work on a recent Wednesday, Schuldt recalled that in his lifetime, the moon landing remains one of the most mind-boggling things that he’s ever seen. At the time, he was 10, and amazed that NASA had figured out a system safe and resilient enough to get humans to the moon and back. Then he got into hiking and experienced phenomena like hair ice.

| Detail, Imprecision Instrument (2003). The work comprises an intricately beaded box with a working compass inside. On the compass are seven languages that Lewis & Clark's expedition team would have heard through a mix of indigenous languages and translators. |

“That system [that got to the moon] is complete baby stuff compared to nature,” he said.

Indeed several pieces are steeped in science, but sobering in their humanity. There is his 2010 The Explorations of Professor Bitz, a beaded anorak that he completed with University of Washington professor and climate scientist Cecilia Bitz. Designed to fit Bitz—”when she was wearing it, she was really wearing her science on her sleeve,” Schuldt said—the anorak shows animals falling from the arctic circle as global warming takes its toll.

At its base, Schuldt has embroidered orange and yellow flames. In the thick of them, a series of black letters and numbers represent a stock ticker for coal and oil companies. There is XOM for ExxonMobil, RDS for Royal Dutch Shell and so on. Beside it, Schuldt's Imprecision Instrument (2003), is a smart and moving curatorial fit—it employs the seven languages Lewis & Clark's team would have heard on its expedition, while seeming to probe the reasonable limits of discovery.

"Jefferson was careful to make sure that Lewis knew he was going into fully populated country," Schuldt said. The piece, he added, is a reminder that the expedition team "couldn't go ten steps" without the help of different tribes that populated the area.

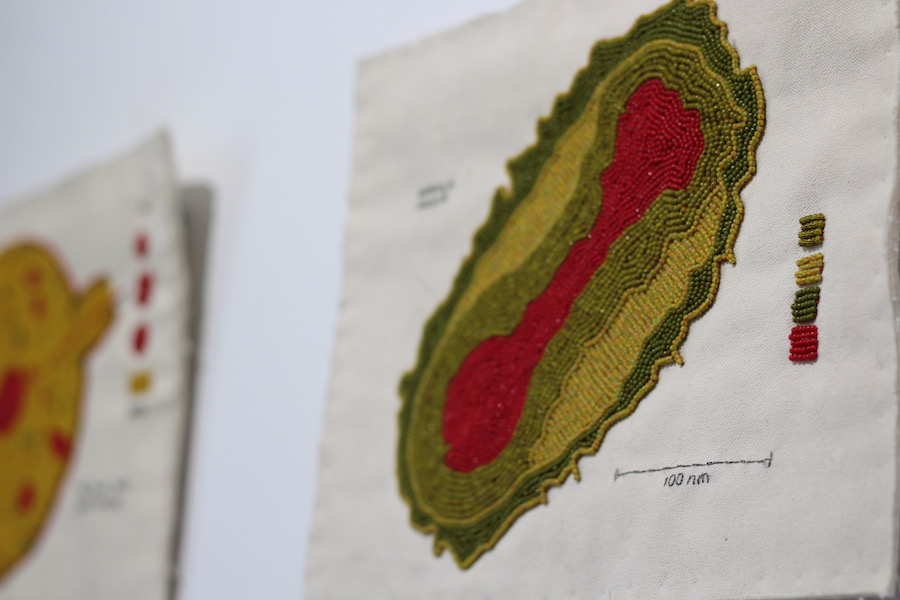

| Detail of the Smallpox virus from Cause and Effect, 2006. |

Or the 2006 Cause and Effect, a glittering triptych with floor plans to two long-abandoned Mandan/Hidatsa lodges, and the smallpox virus that is thought to have ripped through them in the first half of the eighteenth century, as trade opened up on the Missouri river. The virus pulses there, full with an evil it doesn’t even recognize.

“Pre-contact, Mandan/Hitsa villages extended down the Missouri River into Nebraska,” explains an accompanying label. “By 1805, the first village was halfway up through North Dakota.”

Maybe these works gut and anger the viewer, but maybe they move them to action too. On a long wall, the show’s title work winks out with a boy’s young, dimpled face, asking us to come in for a closer look. When we do, we see that the boy is there twice: once smiling in the upper lefthand corner, once smiling under an army helmet at the lower right. He takes a minute to place—the bright-eyed boy from a fruit company ad from the early twentieth century. Around him, the piece takes its inspiration from Smedley Butler, a decorated veteran of the Banana Wars who became a critic of military involvement later in his life.

Even if we don’t need this factoid to get the gist—war is bad, especially war for a country’s natural resources—it adds context. Butler’s soft, laughing face cuts right though an American flag, as does a long black strip, discernible as the stretch of land comprising Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. The same land that was occupied and pillaged, at incredible human cost, for the benefit of U.S. corporations at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Butler, rendered in tight, gleaming beadwork, is surrounded by reasons to oppose it still. In one beaded piece nearby, a soldier poses with a gun at eye level, ready to shoot. In another, Schuldt has embroidered a version of Eddie Adams’ iconic photo from the Tet Offensive, the moment of Nguyen Van Lem’s execution springing back to life. We are transported to the moment: it is hot and dusty and horrible, the smell of sweat and blood in the street, and all we want to do is rewind the fame and undo Vietnam.

On a recent walk through of the show, Schuldt said he doesn’t consider himself an explicitly political artist, so much as an artist whose themes happen to intersect with politics. But the politics are there—a series of recent drawings takes on the Trump administration's fascinations with border walls and sloppy, overblown language (like the president's Tweet that "I love hispanics!"), and lampoons it in exacting detail. Another beadwork warns, with biting humor, about the dangers of technology.

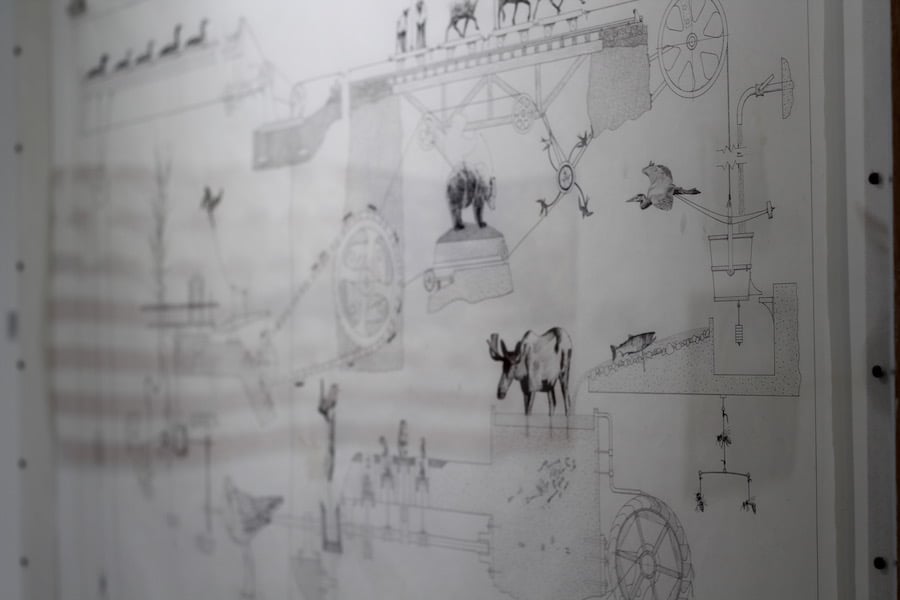

He sees it himself, he said, in pieces like his 2013 Contingency Plan, a drawing that imagines a man made system “to replicate the intricacies of nature after we have destroyed it.”

| Detail, Contingency Plan (2013). |

In the drawing, a set of levers, pulleys and assembly lines gives rise to animals—or at least, machinery that is shaped like animals. Elk trot along an assembly line; birds and big mosquitoes keep equipment running above and below. A huge moose stands in something that looks like a pressurized water tank, with a fish swimming upstream behind him.

As he worked on the piece in his home studio, a bird flew inside and pooped right in the middle of the piece, a big white blob spreading on the vellum. Schuldt recalled being mad for “about two minutes." Then he realized the symbolism was kind of perfect.

“I mean, the problem is, everything is political,” he said.

City Lights Gallery is open Wednesday through Friday, 11:30 a.m. through 5 p.m. and Saturday 12-4 p.m. or by appointment. More information, including an overview of exhibition-related programming, is available at its website.