Creative Arts Workshop | Painting | Photography | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

David Borawski's You Can't Put The Past Behind You. Plastic chain and flag pole ornament with metal bracket. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Black and white plastic flags descend from a hook on the high ceiling, a pink line faintly visible on the outside. Most travel inward while a few stick out of the long, hanging column. Approximately three feet from the ground the flags stop. At the same time, bright white chains become more visible, leading to a string trailing away from the piece.

This piece is one of several in Proximity, curated by artist and teacher Steven DiGiovanni and running at Creative Arts Workshop through June 6.The show features artists David Borawski, John Keefer, Nathan Lewis and Joan Fitzsimmons, all of whom are working across different media. Across two floors, the exhibition challenges viewers to look more closely and find new perspectives in both the artwork and their own reflections on it. The show is also timely: DiGiovanni has used it as a launchpad to talk about the war in Ukraine.

A teacher at Creative Arts Workshop himself, DiGiovanni had been thinking about this particular show since the fall. Originally, he said he considered calling the show Witness, a reference to individual and collective perceptions of the world. Then the war in Ukraine began, bringing with it reports of daily violence and bloodshed. Even though the country was physically far away, DiGiovanni was interested in how close it sometimes seemed.

Top: On the second floor of the gallery, work from all four artists continues. Pictured from left to right are John Keefer's Sanchi #1, David Borawski's The Time Is Right for a Palace Revolution, John Keefer's Burning Container, and Borawski's Two Blows to the Back of Your HeThe word that sprang to his mind was proximity—meant to convey closeness. Although there is no artwork specifically about the Ukraine war, some of the artists are tapped into it, and chose work relating specifically to destruction, nationalism, violence, death, and a surveillance state. Bottom: Detail, John Keefer's Sanchi #1.

Top: On the second floor of the gallery, work from all four artists continues. Pictured from left to right are John Keefer's Sanchi #1, David Borawski's The Time Is Right for a Palace Revolution, John Keefer's Burning Container, and Borawski's Two Blows to the Back of Your HeThe word that sprang to his mind was proximity—meant to convey closeness. Although there is no artwork specifically about the Ukraine war, some of the artists are tapped into it, and chose work relating specifically to destruction, nationalism, violence, death, and a surveillance state. Bottom: Detail, John Keefer's Sanchi #1.

For him, it was important to have each art piece in its own space, so that the viewer could enjoy the work individually and figure out each artworks relationship towards one another. DiGiovanni said that his curatorial style is intensely collaborative, like “making a painting with other people's artwork.”

Across the gallery’s two floors, artists have brought the show to life. On the first floor, John Keefer’s painting Sanchi #2 reveals a faded grid with a boat the color of rust and melted chocolate in the center. Waves crash along the side of the boat, gray in some spaces. Above, a pink-and-white sunrise stretches across the top of the canvas. Thick green, blue, and purple squiggles fill one corner. Reading the title, a viewer connects it to the Sanchi oil tanker collision, which took place in 2018 in the East China Sea. The collision, which spilled hundreds of thousands of tons of oil, was an environmental disaster.

The painting throws a viewer off-kilter, making them second-guess the vision and color palette they see before their eyes. At the bottom left of the canvas, a cloudy, dark brown mixes with a creamy white. A layer of blue enters the mix, as if the sky is trying to peek through. One can see the overlayering of paint where the blue peeks out from behind the dirt-colored paint.

It’s frantic, giving a viewer the sense that the artist kept piling layers aggressively one on top of the other. The longer a person looks, the more details reveal themselves.

Keefer has painted multiple canvases that depict the Sanchi collision, including one upstairs that explodes into bright, busy and cacophonous color. Sanchi #1 is filled with 20 or more layered colors, plumes of dark smoke spilling across the top half of the image. The rest of the skyline is covered with unsettling shades of cream and butter yellow. On the bottom, there is smeared white and pink where the pristine blue of the ocean should be.

Both Sanchi #2 and Sanchi #1 trust a viewer to process the image, and create an outcome of what may be happening in the painting. Both use grids and layering to indicate all the steps it took to create these paintings, and convey a real sense of depth and violence. Both seem like they shouldn’t be part of the natural world, raising questions around how humans perceive, get close to, and turn off the news of violent destruction.

Elsewhere in the gallery, Nathan Lewis' artwork places mixes poetry, narrative panels, collage and skeletal forms, a nod to his ongoing interest in mortality. Beside the first-floor entrance to the gallery, there is the image of two skulls—one photographed or photocollaged, and the other a layered illustration. In front of one skull is a marbled, crescent-shaped dish, its top half facing upwards. The longer one looks, the more rough and broken it appears, like a pottery shard or jawbone that has been exhumed after years in the ground.

“As the maker i'm not in control of those things,” the artist Nathan Lewis said. “I am a viewer just as much as you are.”

In the background of the image is a deserted bird’s nest. Between the two skulls, collaged strips of words read if i can, while words to the left of the outer paper read a fashion a thing. Across the bottom right side, text reads almost to man. The words come from Wallace Stevens’ 1937 poem “The Man with the Blue Guitar.”

It's about the relationship of the public to the artist and the gaps in between, Lewis said in a phone conversation with the Arts Paper. The artist chose these words because he wanted to create a rhyme that worked within the piece.

Lewis, who has many prints and drawings in the show, brings in the question of individual perception and the violence that lurks just beneath the surface of a given image. Upstairs, he has created a piece where, depending on your view, you may see an elm tree or a face. In another, a skeletal form appears to have wings. In a third, a group of people wade into a river, moving quickly. It’s unclear whether or what they’re being pursued by.

“Some of the things you discover along the way is way better than what you set up to do,” he said in a recent phone interview with the Arts Paper. His methods include using a brayer roller to make patterns, cutting up books (he clarified that they are still very dear to him) and making meaning with multiple media in one place. The longer a viewer looks at a salon-style hanging of his prints and drawings upstairs, the more macabre details reveal themselves, more Brothers Grimm than fairytale.

“As the maker i'm not in control of those things,” he said. “I am a viewer just as much as you are.”

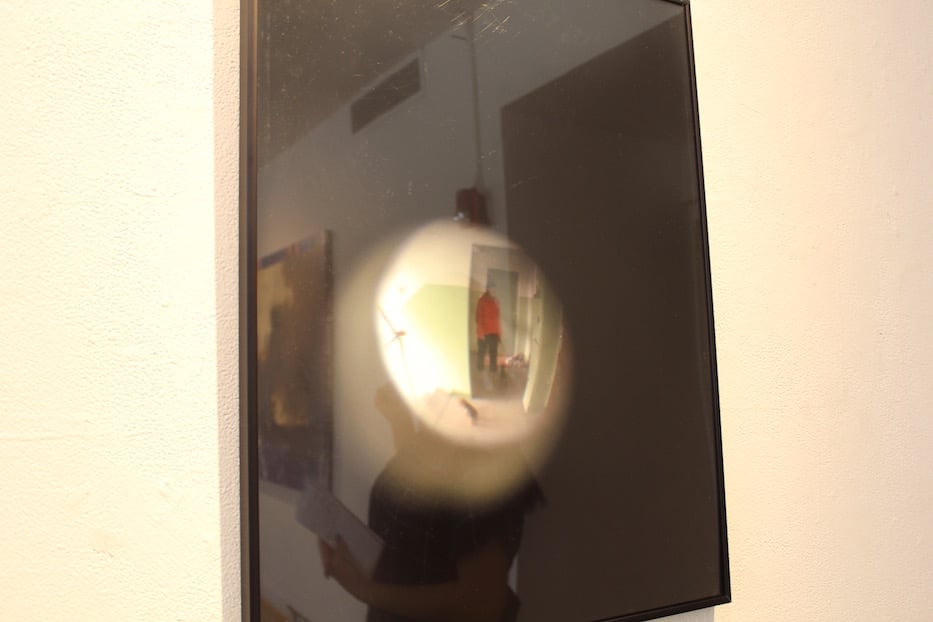

Scenes fromJoan Fitzsimmons' 2007 Surveillance: Warsaw series.

That theme—that one’s original perception may not be what it at first seems—also runs through Joan Fitzsimmons’ photography, scenes from her 2007 Surveillance: Warsaw series installed on both the first and second floor. In 2007, the artist rented a room in Warsaw, Poland from a colleague’s mother after an artistic exchange program brought the two together. The building “belonged to a series of structures referred to as ‘Communist Buildings,’ constructed in that era between World War II and the end of Soviet control of Poland in 1989.”

Staying in the building, “I became my own novella,” she writes i an accompanying text. She would spy on—and photograph—her neighbors and surroundings through her peephole, giving photographs a fuzzy, strange quality of being from a high-security surveillance state.

That’s visible in one such photograph, where a viewer can see half of a green and white hallway and a person looking down. In a red sweater, they stand beside a tall green vertical structure and a brown door. Another piece is, taken perhaps from a lower perspective, shows a smaller version of the peephole. Inside the image, there are stairs that lead to a green and white hallway. A cat strides close to the person standing in it.

Seeing the pieces 15 years later, a viewer might relate to their time during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic—at home, observing the world through a different lens.

Learn more about Creative Arts Workshop here. Juliette Lao is a junior at New Haven Academy. This piece grew out of her three-week internship at the Arts Paper. Read more about NHA's junior internship program here.