Citizen Contributions | Dance | Downtown | Arts & Culture | Yale Schwarzman Center

Candace Michelle Franklin teaching Dunham Jazz. Lotta Studio Photo Courtesy of the Yale Schwarzman Center.

On a recent weekend, a generationally diverse crowd came together for DanceHaven, a program of senior Gabrielle Niederhoffer and the Yale Schwarzman Center. It was a festival of free master classes and a culminating performance celebrating Black artists and the respective vernacular dance forms they practice, preach, and breathe.

DanceHaven was the final product of Niederhoffer’s undergraduate thesis project, created in collaboration with the “Queen of Tap,” Dormeshia. Prior to DanceHaven, Niederhoffer spearheaded Speaking Dance, the culmination of 33 oral histories conducted by the New Haven Dance History Project. It received support from the Yale Dance Lab, of which Niederhoffer is an associate producer and lead researcher.

Throughout the DanceHaven weekend, there were several master classes offered in a variety of vernacular dance forms including African Diasporic Movement, Chicago Footwork, Lindy Hop, Dunham Jazz, Commercial Dance, and Tap, all taught by leaders in the field who were specifically invited by Dormeshia and Niederhoffer. Niederhoffer, who took every single class, said she enjoyed the live music that accompanied the African Diasporic Movement and Dunham Jazz classes, as well as the sense of community that was created within each class.

Kara Mack teaching African Diasporic Movement. Lotta Studio Photo Courtesy of the Yale Schwarzman Center.

DanceHaven culminated in a Main Stage performance by all of the invited teaching artists, their respective dance collaborators and musicians, and the Winard Harper Collective. Just about every chair in the audience was filled with someone eager to see the performance

Harper began the show with a drum solo that led musicians in his band—piano, bass, and sax—into an upbeat, jazz-inflected tune by themselves. Moments later, the audience was listening to vocalist Phillip Hamilton, who sat down by himself center stage with a music stand and a small drum called a doumbek. Hamilton sang, hummed, and drummed until eventually a recording of his own voice became layered with his live self.

His vocals carried the audience into the world of Dunham jazz that Candice Michelle Franklin began to perform. In a flower-patterned dress with yellow bottom fringe, Franklin moved with joy, dynamic rhythm, and intensity. Franklin is certified in Katherine Dunham technique, which combines the legendary choreographer’s approach to Haitian, West African, jazz, and modern dance movement vocabularies.

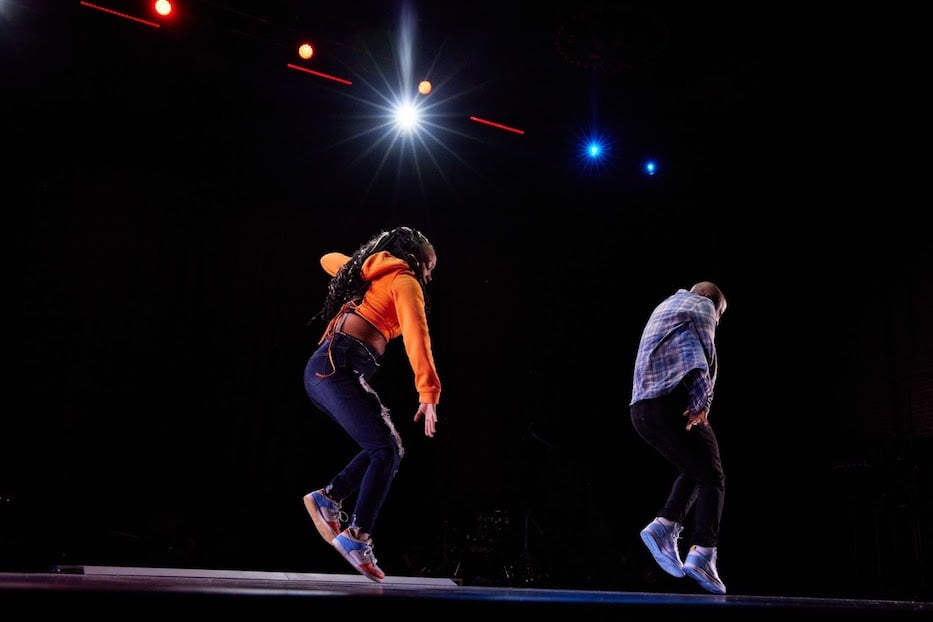

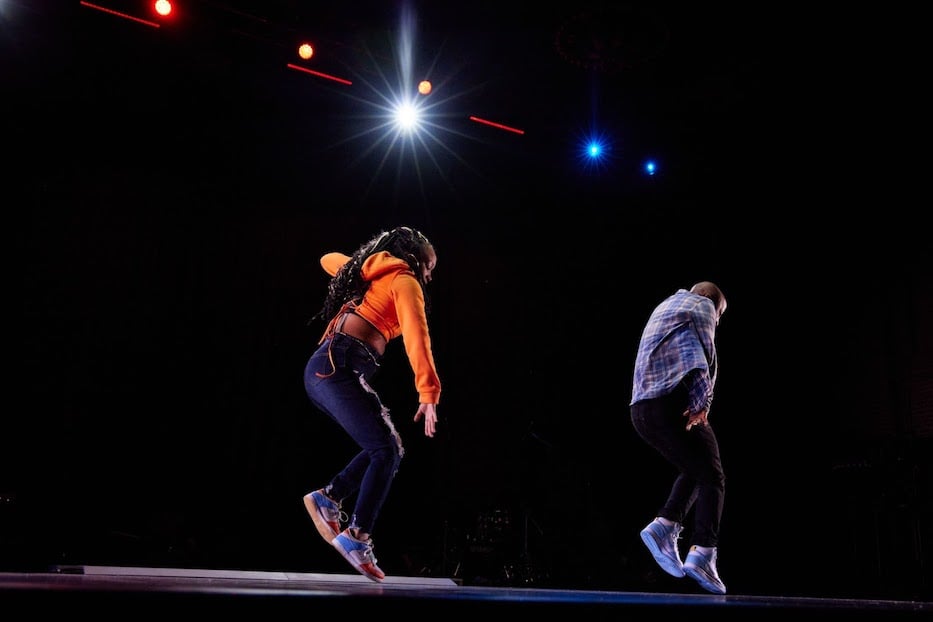

The show then switched gears and transported the audience to the streets of Chicago for a lesson in the complexities of Chicago Footwork. Donnetta “LilBit” Jackson and her collaborator Mike D Chicago entered the stage as characters who had never met, and started to bump into each other for an extremely high energy battle. A playful version of the Pink Panther theme floated over the scene, at one point transformed into an uptempo remix of the song by another Chicago footworker, DJ Corey.

Jackson and Chicago’s footwork was incredibly fast and clean with sharp, dynamic changes in levels. They each had their distinct personal voices in the genre while also highlighting some unison movement that had the audience loudly cheering. This was their lives’ work, and they left it all on the floor.

Donnetta “LilBit” Jackson and Mike D Chicago. Lotta Studio Photo Courtesy of the Yale Schwarzman Center.

As the roaring crowd died down, the energy in the Commons shifted drastically again, this time to an eerily calm silence. A square of light, about 10 by 10 feet, appeared center stage, followed by Lacina Coulibaly in the upstage right corner of the square. Dressed in a black vest and red skirt, the current Yale faculty member acknowledged and thanked the space, then proceeded to walk forwards slowly and deliberately with his hands on his stomach.

He swung, scooched, lifted, folded, and repeated again and again. Covering the perimeter of the square twice fully, he asked the audience to inhale with him as he paused, and exhale as he moved again.

This combination of West African and contemporary movement eventually moved Coulibaly on the diagonal and the square of light left, only for the entire stage to be fully lit. Music began, but his movement was so captivating it was easy to forget it had been silent. He placed his hand on his head, then his heart in swooping, quick gestures.

Everything escalated at once: the speed of movement, the drums in the music, the brightness of the stage. A sense of tension released and joy entered, with large direction changes and luscious lunges that took up the entire stage. Just when Coulibaly had the audience at the edge of its seats, the square of light returned, as did the beginning movement. He tapped the floor seven times with two fingers, walked to the center and bowed. It felt like a celebration of water, land, and life.

Sammy and Candy and the Winard Harper Collective. Lotta Studio Photo Courtesy of the Yale Schwarzman Center.

The Winard Harper Collective returned, but this time with a vocalist. Harper led his band into “It Don’t Mean a Thing if it Ain’t Got That Swing,” and Lindy Hop partners Sammy and Candy entered right after. Dressed in matching blue, silver, and black outfits, and sporting huge smiles, they swung with upbeat energy right off the bat. The dynamic dance duo comprises Samuel Coleman and Candice Michelle Franklin, who met years ago as students at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center.

This was a true lesson in the social dancing that is Black American Lindy Hop. Heads bopped as the two busted out classic moves such as the Susie Q and Charleston, as well as extensive partnering that included cartwheels, backflips, and high split jumps.

Their energy was infectious, and it felt like being at a speakeasy. Sammy jumped over Candy’s head and landed in a split and briefly fooled the audience into thinking he was injured, only to jump right back into partnering with Candy like it never happened. They each took mini solos and then finished with a dramatic layout into a dip.

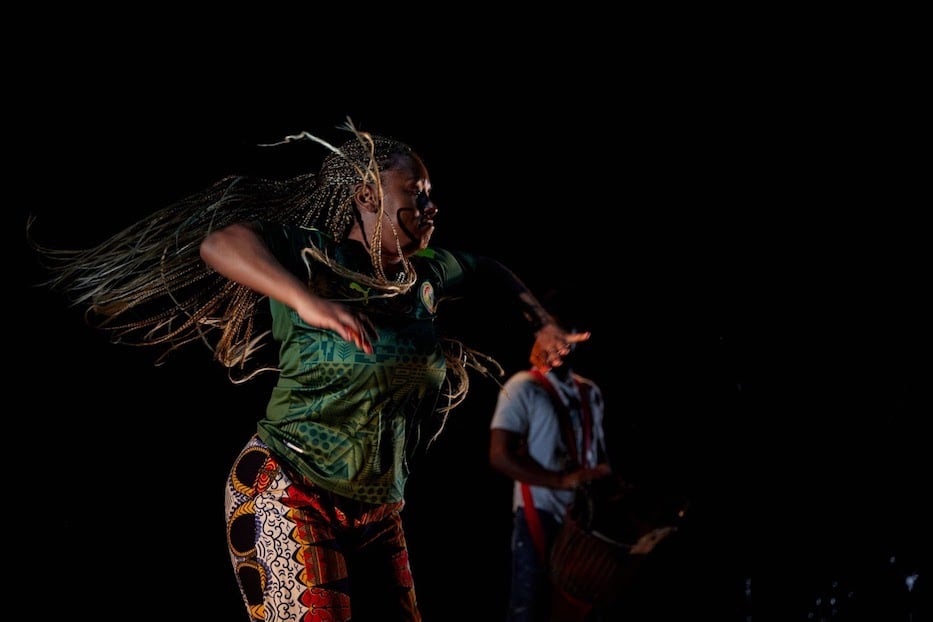

Kara Mack and Sanu Basu. Lotta Studio Photo Courtesy of the Yale Schwarzman Center.

Then, the audience was plunged into silence again. A recorded voice began to speak in the dark. What the naysayers have in common is fear of light…you are made to dance your journey…djembe, conga, kalimba…so you dance and dance ever forward.

Kara Mack’s voice faded, and wave sounds entered, only to soon be interrupted by Sanu Basu loudly playing the djembe while slowly entering from upstage left. Basu established a clear groove full of dynamics and accents. He strayed from the groove to playfully explore other rhythms, only to return the audience back home to the initial groove.

With her striking braids, Mack entered and immediately took up space, bouncing and smiling.The two shared a call and response between her voice and his drum, which sparked large and fast West African diasporic movement from her body.

She contemplated her next move while handing her hair elastic to Sanu, then grabbed the mic, calling “What’s up my people?” She explained her top half, a soccer jersey, was contemporary, and her bottom half, patterned West African pants, was tradition.

“The djembe instrument came with my ancestors to this country in the 1500s. In 1740 the instrument was illegal, forcing the resilience of my people that is still alive, and forcing us to find new ways to keep percussion alive.”

Within moments, she was engaging the audience. House left was responsible for clapping the downbeat, house right clapped “baba” on “and one, and three,” and house center shouted “HUH” on the one. “You gotta keep me dancin’” Mack said to the audience, and then proceed to move while singing a song her grandmother taught her.

Come along my friends, and get aboard and ride this train, nothing on this train to lose, everything to gain, she sang. Footwork ensued as she continued to dance, sing, and slowly exit upstage with Basu.

The Winard Harper Collective returned for the last time, and the Queen of Tap (pictured at left by Lotta Studio) took the stage. Only the wooden platform specifically designed and miced for tap dance was lit, and Dormeshia, wearing her signature gold shoes, broke out into a hard a capella groove.

The Winard Harper Collective returned for the last time, and the Queen of Tap (pictured at left by Lotta Studio) took the stage. Only the wooden platform specifically designed and miced for tap dance was lit, and Dormeshia, wearing her signature gold shoes, broke out into a hard a capella groove.

She opened into a three-and-a-break with seven flaps and a heel, allowing room for the vocalist to begin, and then shifted into a flurry of crisp and clear 32nd notes. Dormeshia skillfully alternated between 16th notes, 32nd notes, and triplets, then back to grooving. She was singing with her feet, seemingly effortlessly, the audience gripped onto every note.

The rest of the instrumentalists from the band entered, and Dormeshia began swinging hard, eventually finding herself in an exploration of stunning accents throughout paddle and roll. She traded bars with the drummer, Harper, and they had a lively conversation. The two percussionists were so clear and in tune with each other, that you could close your eyes and have no idea whether you were hearing two tap dancers, or two drummers. The piece ended with a nerve tap (hitting extremely quickly) on the ball of her foot. It was absolute perfection, and the audience knew it.

Dormeshia grabbed the mic and all of the performing artists came onto the stage for a big finale jam session. Thelonius Monk’s “Rhythm-A-Ning” rang over the audience. As they played, Jackson donned her tap shoes this time for a brilliant tap solo.

Phillip Hamilton took a magnificent scatting solo and then invited the vocalist of the Winard Harper Collective to solo as well. By Dormeshia’s invitation, everyone in the band soloed, ending with Harper himself. His final drum solo sent the audience into a united standing ovation.

Lotta Studio Photo Courtesy of the Yale Schwarzman Center.

During a post-show talkback, moderator Amanda Reid noted that vernacular dance can mean different things to different dancers.

“Vernacular means it comes from a culture,” said Franklin. “Research to stage methodology, it is culture on stage.”

“If you start from the seed instead of the tree, then you’re good to go,” added Mack, “Digging deep is what creates new things, vernacular is the source.”

An audience member then asked the artists how artists approach preservation versus innovation.

Dormeshia said she maintains integrity by staying rooted in tradition. While some of her grooves are contemporary, everything is based on that foundation. “Innovation scares me, I don’t wanna go so far from home as I might not find my way back,” she said.

Elka Samuels Smith of Divine Rhythm Productions aided in this production and the artist management. She said it has been an honor to be involved in Dormeshia’s residency at YSC and collaborating in bringing Black art to Yale “which is clearly needed, and we hope to do more of it.”

We hope to see more of it, too.

Alexis Robbins is a tap dancer and educator in New Haven and Hamden.