Screenshots via Zoom.

LaToya Howard still remembers the first time she read “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou. And the second. And the third. The poem made her feel confident in her Blackness, enough to come back to it over and over again. Decades later, she’s watching a program do the same thing for students—and parents—at her daughter’s school.

Howard is president of the Family Teacher Organization at Elm City Montessori School (ECMS), where her daughter Corinne is in the second grade. Wednesday evening, she joined two dozen parents, organizers, and educators for a presentation on One Book, One School, a program that ECMS has launched as part of its mission to build a learning environment centered around Anti-Bias and Anti-Racism (ABAR) work.

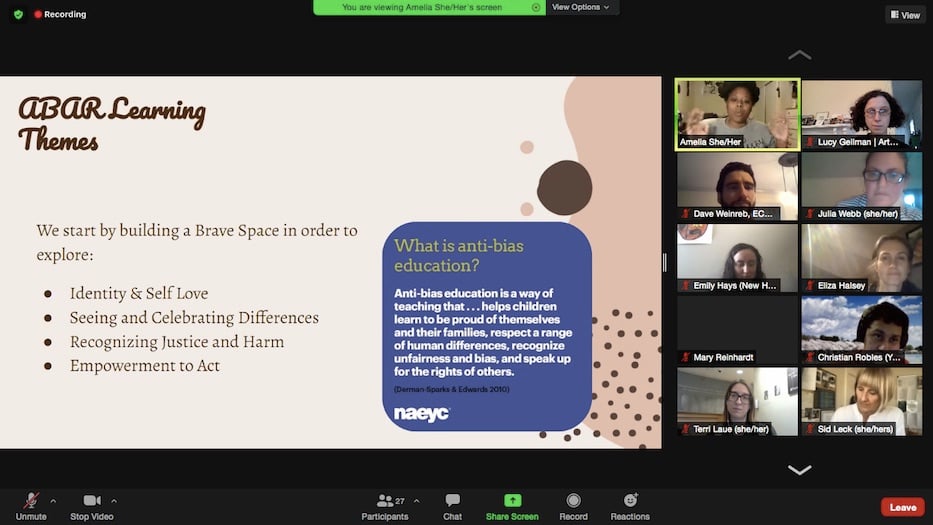

The program was led by ECMS Anti-Bias, Anti-Racism Director Amelia Allen Sherwood and school Principal Julia Webb. Their hope, they said, was to give fellow parents, guardians, and educators a template to bring into their own schools and learning spaces. Currently, the One Book, One School curriculum does not exist within the New Haven Public Schools more broadly.

Sherwood (left) reads last summer at a Juneteenth teach-in in East Rock Park. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

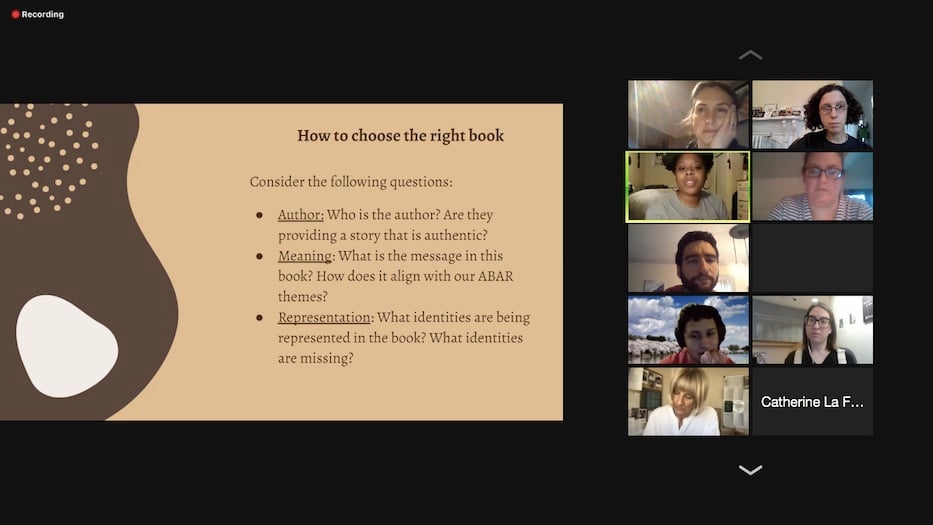

“This sets the stage for deep conversation around identity, differences, injustice and activism,” said Sherwood, who is the only in-school, full time ABAR educator in the district. “At the end of the day—Britt Hawthorne says this too—we’re not going to give you a book list. It’s just more of like, you have to create a book list that affirms your specific classroom, your specific school, your specific community.”

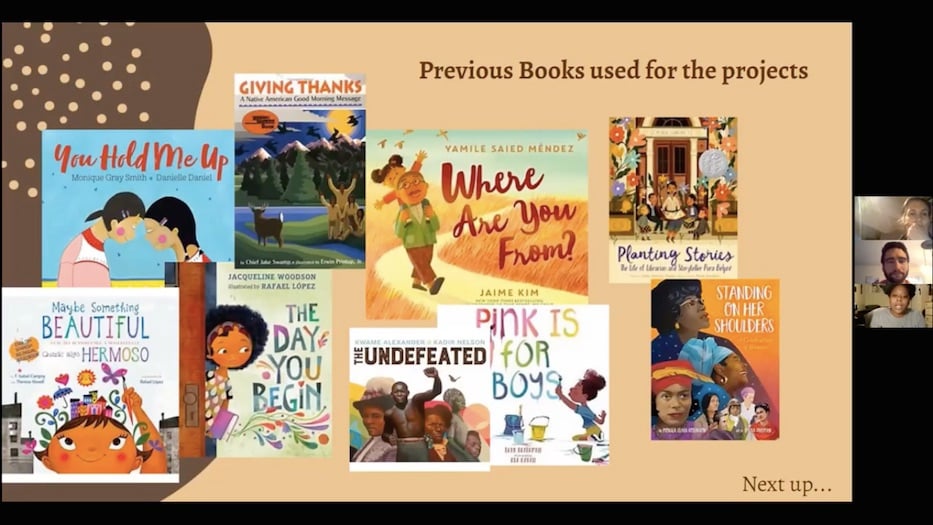

The format of the program is straightforward by design. Each month, ECMS students from pre-kindergarten through sixth grade read and discuss the same book with their teachers, in a process that often goes beyond their classrooms and translates to discussions among peers, siblings, and families. In addition to the books themselves, the school devised a teaching template so that educators can share resources and hold discussions around the book. Often, books also fit in with the time of year in which they are taught.

In November, for instance, students read Giving Thanks by Chief Jake Swamp and illustrated by Erwin Printup. This month, which coincides with the start of Ramadan, students will be reading The Proudest Blue, written by Olympic medalist Ibtihaj Muhammad. In 2016, Muhammad made history as the first Muslim athlete to compete—and win—in a hijab. The book follows a young Muslim girl as she selects a brilliant blue hijab and wears it to school, learning to both address and leave behind the racism, scrutiny, and ignorance of peers that she finds at school.

In selecting the books, educators focus on the same principles of self-love, intersectionality, and a family- and student-led educational space that are part of the school’s mission. In addition to centering authors of color, particularly Black and Indigenous voices, teachers and staff make sure to avoid books that reinforce harmful stereotypes or internalized racism, ableism, and patriarchy. For example, Sherwood said, teachers found that the book Chocolate Me wasn’t a good fit for the school, despite the fact that it’s written by a Black author.

In the story, written by the actor Taye Diggs, white students tease a young Black protagonist about his dark skin, wide nose, and curly black hair. When he goes home dejected, his mother teaches him about the beauty in his Blackness, using chocolate as an analogy. The next day, he wins fellow students over by making them chocolate cupcakes. Sherwood explained that the book leaves Black students with the harmful message that it’s on them to break the cycle of bullying.

She added that One Book, One School is part of creating what she calls a “brave space,” which moves into a conversation where students—and often, their parents and educators—may find themselves dealing with new, unfamiliar material that challenges their perceptions of the world. When students read Robb Pearlman and Eda Kaban’s Pink Is For Boys earlier this year, teachers used it as a chance for their classes to identify, discuss, and dismantle harmful stereotypes. For instance, the age-old one that girls wear pink, and boys wear blue. When a few families called the school with questions and concerns about the book, Sherwood and Webb were ready to talk about them.

“When you’re talking about something so toxic around racism, when you’re talking about bias and thinking about this safe space, it’s not going to feel safe for you emotionally,” Sherwood said. “When we say safe space, we’re not allowing compassionate accountability to live in truth-telling and conversations that are really important to us right now.”

Throughout Wednesday’s presentation, she encouraged attendees to think about books that they’d found affirming in their own childhoods. For Jamila Mapp, a teacher at Bala House Montessori School in Philadelphia, that book was Eloise Greenfield’s Honey, I Love, which “made me feel love and see what Black love felt like as a family.” Howard said that Angelou’s poetry marked the first time “I felt empowered ... and I needed to feel empowered in my Blackness.”

Terri Laue unmuted herself in praise of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s 1908 Anne of Green Gables. Over 100 years later, the book still affirms Laue’s lived experience as a member of the LGBTQ+ community. She said that while it isn't specifically a queer book, she related to Anne's struggles of not fitting in, and navigating her own way in the world.

“Anne of Green Gables, really made me feel seen as a queer child,” she said. “Just, it was very affirming in a way that I didn’t have the words to understand. It was great, because my very conservative grandfather and I could read Anne of Green Gables together.”

As a public charter school, ECMS is the only school in the district with a dedicated anti-bias, anti-racism director, and the only one to formally roll out a program like One Book, One School. The New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) district recently announced Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR), designed to give high school students and staff members with whom they work a platform for anti-racism and equity work in their schools.

Webb added that One Book, One School has opened up discussions that dovetail with other parts of the curriculum, from repatriation and Indigenous land to Black History Month projects. Both she and Sherwood cautioned educators to choose books that reflect their students’ lived experiences, and undo the racism and bias that is so often taught—even if unintentionally—in schools.

“We think that this One Book, One School project is beautiful, and we don’t want people to think ‘hey, if I just read a few picture books, then I’ve done all the work," Webb said. "Cause there’s a ton of work that we gotta do before, and it also is in concert with a whole experience of what it means to be a student, a teacher, a human, a family member, all of those things.”