Ely Center of Contemporary Art | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

Grayce Howe Photos.

On the first floor of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art (ECoCA), a dozen asymmetrical, scoop-shaped cast metal fragments face the ceiling, their edges curling upwards. Tracks cut across the surface, surprisingly neat for the chaos they often suggest. The surfaces glint beneath the gallery’s lighting.

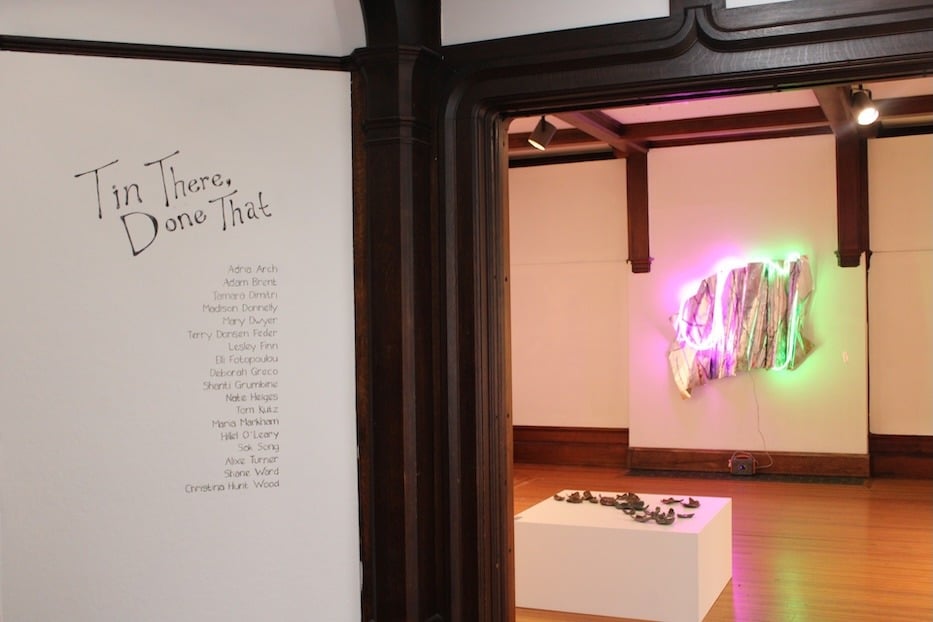

Across the room, a network of wires weaves in and out of green and purple neon lights, the color bright and eye-catching in this gray-toned room. One room over, several stacked, repurposed plastic milk jugs wait to make their mark. From a certain angle, they look as though they are melting into each other.

Welcome to Tin There, Done That, now up at ECoCA through April 20. Curated in honor of the organization’s 10th anniversary, the show showcases and celebrates tin and aluminum—metals traditionally given 10 years into a marriage or partnership—showing how diverse the materials can be. Artworks range from crushed cans, dried up mud, and delicate metal sculpture to paintings and three-dimensional prints. As of this month, they also feature tin can luminaries and tiles from workshops held in late March.

The show features artists Adria Arch, Adam Brent, Tamara Dimitri, Madison Donnelly, Mary Dwyer, Terry Donsen Feder, Lesley Finn, Elli Fotopoulou, Deborah Greco, Shanti Grumbine, Nate Heiges, Tom Kutz, Maria Markham, Hillel O’Leary, Sok Song, Alixe Turner, Shane Ward, and Christina Hunt Wood. This month, the show joins a celebratory 10th anniversary gala on April 26 at 5 p.m. at CitySeed’s 162 James St. building.

In Tin There, Done That, some artists make use of the material directly. In Mary Dwyer’s mixed media Grace Ely, 2018, for instance, an acrylic painting imagines Grace Taylor Ely holding a badminton racket made from tin. Ely, rendered as a petite woman in a long green skirt, tips to her right (the viewer’s left), popping from a field of pink-orange color.

Neat yellow lines criss-cross the blocks of pink, as if they could be a window frame or a badminton net seen from above. As Ely lifts the racket into the air, the figure seems to jump slightly, potentially engaging in a match. Because the work is a painting, it flattens life into two dimensions, giving it an illustration-like quality.

Adam Brent, Milk Jugs, 2025, Printed Plastic, Aluminum, Resin, Acrylic Paint.

“A few years back I did some research on Grace Ely,” Dwyer writes in an accompanying label. “I found that Grace loved music and nature. She opened her home to children afflicted with fluency disorder and encouraged them to sing. She brought musicians to the local hospital to play music. Grace was known to walk her two dogs Happy and Major in this Trumbull Street neighborhood. She played tennis and badminton and practiced calisthenics. I would have liked to have met her.”

Other artists use a much more abstract and broad use of aluminum—casting dried up mud, making neon light designs, and paintings on aluminum surfaces. Take Tamara Dimitri’s Imprints, 2025, a collection of cast bronze and aluminum imprints that—at least from afar—look as if they could be dried mud. The different patterns range from heart shapes to tire tracks; the jagged, uneven sides of each sculpture make each little piece its own.

In an accompanying label, Dimitri explains that the work is both old and new: she completed it two decades ago, when she lived in Arizona, but has not shown it until now.

“I spent time in the desert on foot and on my bike and markings in the desert soil often remain for months due to limited rainfall. The more time I spent in the desert, the more careful my steps became in an effort to avoid disturbing the fragile ecosystem,” she writes.

In Unfolding Currents - Neon Flux, 2025, a sculpture by Sok Song, a large piece of folded metal acts as the foundation of the piece. Surrounding the metal in every direction are thin pieces of wire, intertwined with one another at points, and encircling the piece of metal on every side. Alongside them, a set of coils adds a bright glow in neon green and purple. The lights contrast the rest of the sculpture, highlighting the chaos it encompasses.

“This piece extends an ongoing exploration of materiality, transformation, and identity through the act of folding,” the artist writes. “Aluminum, a material both rigid and pliable, serves as a structural and conceptual foundation. By folding, creasing, and manipulating its surface, the piece resists fixed form, embodying movement, redirection, and tension. The painted and marked lines follow these folds, shifting as they catch the light—interrupted, bent, and redefined by each crease.”

The show joins plans for an April 26 benefit gala that celebrates the building’s long history on Trumbull Street. After the passing of her husband John Slade Ely in 1906, Grace Taylor Ely took ownership of the mansion that the Ely Center now resides in. She passed away in 1960, but stipulated in her will that she wished for the property to remain in the arts.

For years, it has. While 51 Trumbull St.has gone through several curatorial and creative transitions in the past years, it has remained a rotating door through which many of the city’s artists have passed. During that time, it has also braved choppy financial waters (the house went up for sale in 2016, and again in 2022) and had a reckoning with many in the city’s arts community that still feels like a work in progress.

“It’s a really special space and it’s fun to have an unconventional gallery space,” said Ely Center gallery director Aimée Burg, who has worked there for about a year.

It’s easy to see the charm. The floorboards creak when moving from room to room, and the doorways form a welcoming entrance to each part of the gallery. On the first floor, there’s a front desk stationed in front of the grand staircase where a portrait of the late John Slade Ely hangs. In one room of the gallery there’s a fireplace, as well as a bay window. The history of the home seeps into every corner and crevice, palpable as a person walks through.

“The non-profit was officially a non-profit about 10 years ago since we’re turning 10,” Burg added.

Grayce Howe was the Arts Paper's 2024 New Haven Academy spring intern and is now in her senior year. The New Haven Academy internship is a program for NHA juniors that pairs them with a professional in a field that is interesting to them. Grayce plans to continue writing for the Arts Paper throughout her senior year, so keep an eye out for her byline in these pages!