Beinecke Library | Black History Month | New Haven Museum | Yale

"Shining Light on Truth" at the New Haven Museum. Photos Kapp Singer.

"Shining Light on Truth" at the New Haven Museum. Photos Kapp Singer.

Merging onto I-95 heading south, you pass over the northwest corner of East Street and Water Street. Today, it’s a fenced-off, overgrown embankment spilling off the side of the highway. But in 1831, it was to be the site of the nation’s first Black college—that is, until New Haven’s then-mayor called a fateful town meeting where the city’s property-owning Whites voted down the school plan by a margin of 700 to four.

The story of Simeon Jocelyn, William Lloyd Garrison, and Arthur Tappan’s historic attempt to build the college—and why it failed—was told on Saturday in a film screened at the New Haven Museum. The 24-minute short by Tubyez Cropper, entitled What Could Have Been: America’s First HBCU, was shown as part of the opening event for the exhibition “Shining Light on Truth,” which examines the “essential role of enslaved and free Black people in New Haven and at Yale.”

The exhibition—presented by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and Yale University Library in partnership with the New Haven Museum—was curated by the Beinecke’s Director of Community Engagement Michael J. Morand with Charles E. Warner, Jr., and designed by David Jon Walker. It runs Feb. 16 through summer 2024 and includes findings from David W. Blight and the Yale and Slavery History Project’s new book Yale and Slavery: A History, which is available online for free. Admission to the museum is also free for the duration of the exhibition, underwritten by Yale.

“These are stories of Black history, which is just another way of saying they are stories of New Haven history, of Yale history, of Connecticut history, of American history,” Morand said.

“Official institutional history tends towards hagiography,” Morand added, explaining that Yale has often ignored past research into the university’s connections with slavery—namely, a 2001 report by Yale doctoral students published by the Amistad Committee.

“Let us declare, the days of obfuscation are done,” Morand said.

Tubyez Cropper (top) and Michael Morand (bottom) speak at the exhibition opening.

Tubyez Cropper (top) and Michael Morand (bottom) speak at the exhibition opening.

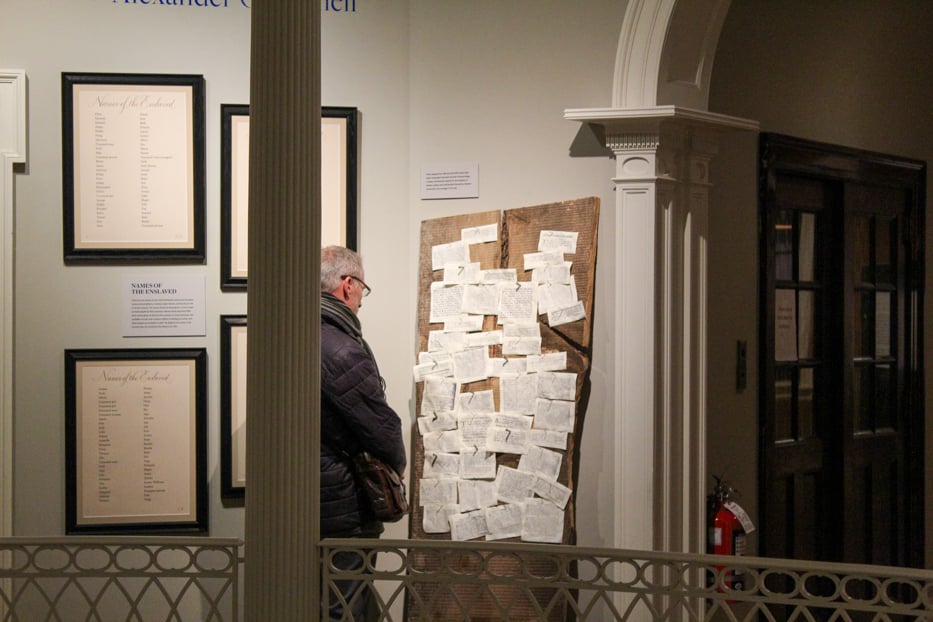

The exhibition winds clockwise around the rotunda on the museum’s second floor, beginning with the story of how slavery affected New Haven’s economy and the early history of Yale.

Featuring 18th and early 19th century clippings from New Haven newspapers which document the sale of enslaved people and advertise rewards for the capture of those who attempted to free themselves, the show’s opening section lays bare the magnitude and recency of slavery in the Elm City. The clippings sit beside a list of the names of over 200 people who were enslaved by Yale affiliates—university presidents, professors, major donors, and others. In several entries, the list simply identifies people as “Unnamed man” or “Unnamed woman.” “The absence of a name in the records does not constitute the absence of a life,” reads a plaque.

“They’ll make you weep,” Blight said of the list of names, expressing his admiration for the “sheer depth” of the research showcased in the exhibit.

“I don’t know what else to say. It’s amazing,” he added.

Newspaper clippings (right) and the list of names (left).

Newspaper clippings (right) and the list of names (left).

As much as the exhibition foregrounds the dehumanizing violence of slavery, it also offers stories of Black resistance, community, and success in the city. Wall text chronicles the work of Jupiter Hamilton, “the first published Black American poet” who wrote hopeful verses on abolition, and recounts the work of William Grimes, who “published the first autobiography written by a formerly enslaved American” in 1825. Viewers can also read about the establishment of the city’s Black churches in the early 19th century, which still serve as important spaces for education and organizing.

This counternarrative comes to its apex in what exhibition organizers call the “1831 room.” The space, two-thirds of the way around the rotunda, draws attention to the Black college proposal killed by the city’s leaders and also celebrates the successes of early Black students at Yale. Over 200 portraits of these students—from physicist Edward Bouchet to abolitionist James W.C. Pennington—adorn the walls, and bookshelves feature texts by and about them.

Charles Warner speaks to visitors in the "1831 room."

Charles Warner speaks to visitors in the "1831 room."

“When you hit that room—for me, it was like that ancestor spirituality flowed straight through me,” Dee Marshall said. “That 1831 room should be a permanent exhibit.”

“To see those beautiful people up there…”

Among the photographs hangs a large seal for the HBCU that never came to be, which the curatorial team created to honor the proposal. In bold white text on a black background, “1831 COLLEGE” arcs across the top of the banner, and “KNOWLEDGE IS POWER” across the bottom. Beneath the seal sits an empty bookshelf which, as a sign indicates, “bears witness to the books not written by the students who did not go to the Black college not built in New Haven.”

The "1831 room."

The "1831 room."

“Consider what was lost and what could have been. And think about what could be,” the sign prompts.

For Denise Manning Keyes Page, the exhibition was personal. She had always known her maternal grandfather, Edward William Manning, attended Yale’s School of Fine Arts (now the Yale School of Art) from 1913 to 1915, and that his ancestors were enslaved. But beyond this, her family history was unclear—her mother was orphaned at age seven and never learned about her lineage.

“I had always asked my mother, ‘So how did your family come here?,” Page said.

While preparing for the exhibition, however, researchers uncovered further information about how Manning’s grandfather had bought his freedom in North Carolina and moved to New Haven during the Civil War, and that Manning’s uncles, Henry Edward Manning and John Wesley Manning, both graduated from Yale (that history is detailed in an “Interlude” between chapters 9 and 10 in Yale and Slavery). For Page, this discovery was unexpected—she did not think that the project, which focused on slavery at Yale and in New Haven, would concern members of her family, who arrived in the city already free.

“It really is serendipitous that the connection was even made,” Page said.