Music | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

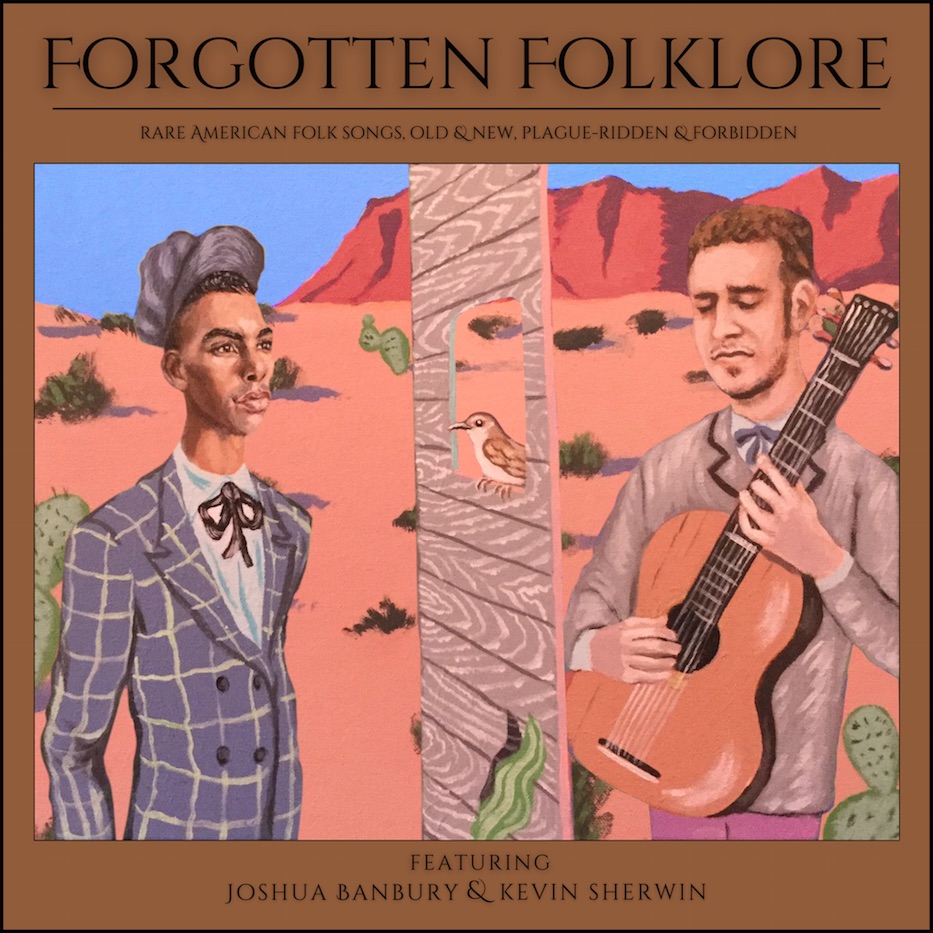

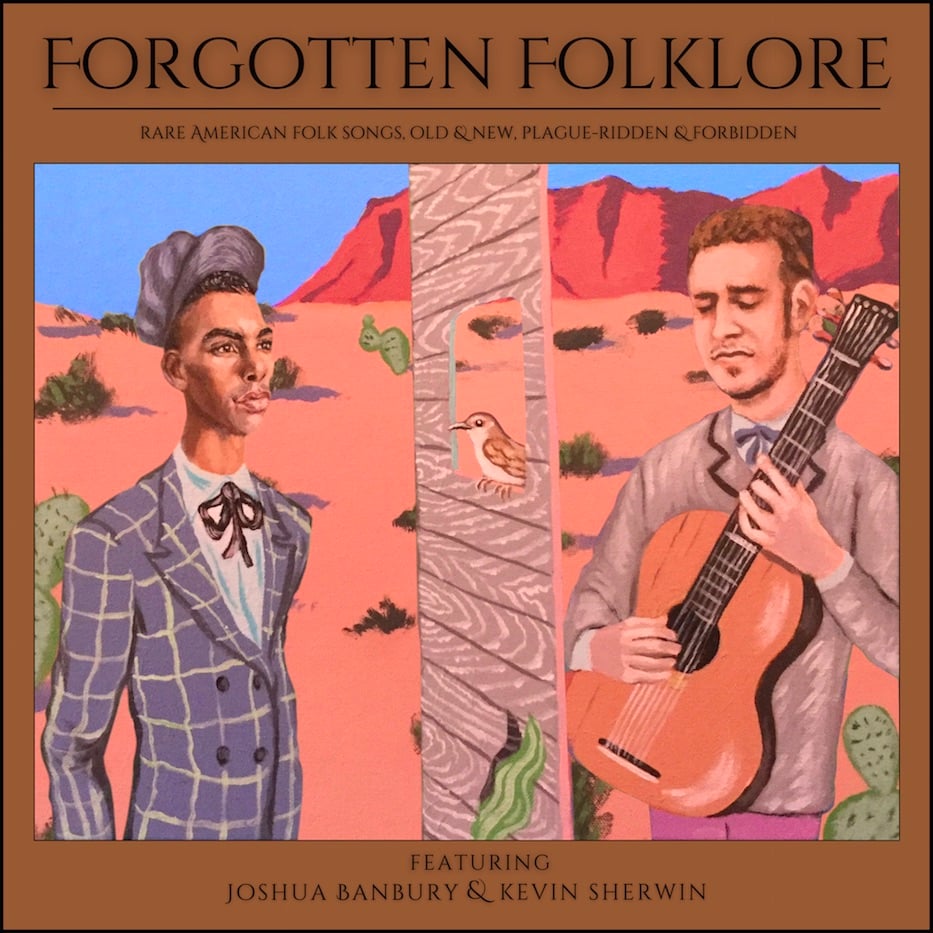

Cover art by Bruno Leydet. Forgotten Folklore Photo.

Static crackles over the track, pulling the listener back in time. Joshua's Banbury's voice is lush but somehow also spare, holding the weight of each word as the verses dip and chirrup. He slides into his role as storyteller, giving the song wings as it escapes from somewhere between his throat and his ribcage.

"The cuckoo, she's a pretty bird," he sings, his voice undulating. "She sings as she flies/She brings us glad tidings/And tells us no lies."

"The Cuckoo" comes off of Forgotten Folklore, a new album from New Haven-based musician Kevin Sherwin and Austin, Tex.-based Banbury. A product of the pandemic, the eight-track compilation seeks to celebrate and amplify folk music that may or may not be forgotten, depending on who a listener asks. It is available through Spotify and YouTube.

The project is supported by the YoungArts Foundation, through which the two met several years ago in New York, and the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings. It received production help from London-based producer Fraser McKnight and cover art from Canadian artist Bruno Leydet.

"Music has a lot of cultural significance," Sherwin said in a recent interview on Zoom. "And it's multilayered, and complicated, and beautiful because of that. Josh and I kind of dove headfirst into all that meant, from a history side to a personal side."

While the two started working on the project during the pandemic, both have nursed an interest in American folk music, and particularly historical sound recordings, for much longer. Born and raised in Austin, Banbury fell down the folk rabbit hole five years ago, when he was recovering from a “really dramatic” breakup and living alone in Baltimore. It made him feel closer to his home state of Texas.

As a classically trained musician who is also Black and gay, he felt like his world was opening up in front of him as he listened. He became especially interested in sisters Jean and Edna Richie, who became an aural gateway to Appalachian, Texan, and contemporary folk. He started listening to artists Jessica Pratt and Adrianne Lenker. He thought about what it looked—and sounded—like to reclaim that history after years of singing French, German and Italian classical music.

"I didn't have to stand in front of a piano, I didn't have to introduce a song and stand in a certain way and wear costumes that my people never would have worn," he said. "I felt more and more connected to my ancestors by discovering this music, and discovering that enslaved people sang more than spirituals.”

He and Sherwin, who had met a few years before, were still in frequent contact. When Banbury began writing a play about folk music in 2018, Sherwin made the trip from New Haven to New York for a reading of his work. In the play, a Black Ivy league student travels to Kentucky to study banjo and dulcimer, both of which connect American folk to much older musical traditions in West Africa and the Middle East. Then he “gets stranded” living with a family of Donald Trump supporters, Banbury said.

“I came into folk music the same year that Trump was elected into office,” Banbury said. “And it was very interesting, the paradigm of being someone who was Black and queer, but also interested in something that most people associate with poor white people in West Virginia or Kentucky. With everything politically that was going on, sometimes I wondered, like, ‘Does this connect me with Trump supporters in any way?”

It gave the artist a chance to poke at some of the questions he was asking himself, including who got to lay claim to and perform folk music, whether white people were ready to talk about its non-Western roots, and if he was enabling Trumpism in some way by performing the music.

Sherwin “was incredibly supportive of the project,” Banbury said. He started sending Banbury sheet music transcriptions and sound recordings from Yale's Music Library, where he had once worked as a student and fallen in love with its collection of 280,000 historical recordings.

It opened Sherwin’s world, too: the more research he did, the more he fell in love with the recordings of ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, and work of Huddie William "Lead Belly" Ledbetter, Lightnin' Hopkins, Dock Boggs, Muddy Waters and others. Those musicians aren’t forgotten within folk and traditional communities, he acknowledged—but they’re also not widely celebrated in the mainstream.

He became entranced with “that very thin membrane” that lives between folk, country and blues, aware that musicians were passing styles on to each other across genres. The longer the two talked, the more it seemed like they should be collaborating on a project. Then, in March of last year, the pandemic hit.

Banbury moved back to Austin to be closer to his family. He found that folk songs once again became a source of comfort in an increasingly dark time. While "folk music is certainly communal," he practiced works that channeled the same isolation he was feeling. They were songs filled with tradition and heart that he could also listen to while doing the dishes and watching the world shut down.

"I think folk music really saved me in that way this past year," he said. "To sing a full song, I didn't need a pianist. I didn't need an arranger. I didn't need anything but my voice and the room that I was in."

With performances largely postponed and cancelled, "I just felt it was a perfect time to regurgitate everything I had been consuming," he added. After he and Sherwin secured funding from YoungArts, they began work on the project in the fall of last year. Because they were over 1,800 miles apart, Banbury would record, and then send tracks to Sherwin. Sherwin, who played the banjo for the first time on the album, recorded his own tracks, and then mixed everything.

"Once Josh and I started working on the music, we kind of got into our own worlds," Sherwin said. "Like, what are our ideas, what melodies are we coming up with? What's the harmonic soundscape of this going to be like? So we kind of worked intuitively after that."

The result is an album that makes their reverence for the tradition clear—and at its best, makes it their own. Sometimes, tracks are remarkably clean and sharp-edged, which is exactly what one might expect from two classical musicians who decided to make a folk album and studied the music rigorously before they were satisfied with it. The banjo, which Sherwin learned for the album, is heavy on his training in classical guitar, but also gets the style down after hours of practice.

Banbury is an emotional performer, and he shines most when he gives himself over to the music (he also did some of the writing on the album, making it a true meeting on past and present). In “Boll Weevil,” he channels Vera Ward Hall’s recording of the song, but lets his voice become bendable and exuberant at the edges. His take on The Stanley Brothers’ “Come All Ye Tender Hearted” is stripped down and makes the narrative interludes feel more like a spoken word piece.

By “Wild Bill Jones,” a listener can tell he has relaxed enough to have fun. As Sherwin plays beneath him, there’s laughter in his voice. Sherwin has mixed in the clatter of dishware and ambient conversation, and it makes the work track feel alive, as ready for 2021 as it was for Eva Davis in 1924 and Boggs in the 1960s. When Banbury asks after Jones’ fate at the end of the song, his sheer delight comes right through the album.

He said that the experience was ultimately communal “in a very 2020 sense”—the album includes two musicians working across almost 2,000 miles, and a creative team spread between the U.S., England and Canada. During the time that they were producing it, they couldn’t have easily visited each other even if they wanted to.

"It's just such a great time capsule," he said. "When we look back at this 10 years from now, I'm gonna have memories of like, the plague, and making music, and Donald Trump, and everything that fueled this project. I think that when we revisit it, it's gonna be—"

"Quite a little treasure chest of memories," Sherwin finished.

Going forward, the two hope to turn Forgotten Folklore into an educational opportunity. As the world continues to reopen, they see bringing the project to museums, classrooms, universities and the occasional classical music festival that will have them.

This fall, Banbury plans to move back to New York City because Austin has become too expensive for him as an artist. He said he sees a disappearance of the culture he so loved as a young performer just coming into himself.

He's also hoping to make folk easier and more accessible for other artists who look like him—a path that Rhiannon Giddens, Leyla McCalla, Justin Robinson and many others have been paving for years. When Banbury was studying and performing classical music, he often got pushback if he brought up folk music for a recital. If he insisted on an Appalachian ballad, he said, faculty pushed him toward spirituals instead. He wants to change that for future generations of classical musicians.

"Black people were singing all kinds of music around the time that they were enslaved," he said. "Not just spirituals. It's important for me to pay respect to the people that have paved the way for me to sing today, and to continue the legacy of making music in that way."

Forgotten Folklore is available on YouTube and Spotify. Listen to the full album here.