Downtown | Education & Youth | Lotta Studios | Photography | Arts & Culture | Westville | Indigenous rights | Arts & Anti-racism | Westville Renaissance Arts (WRVA)

Top: Laura Fuller-Weston and Kim Weston outside of the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, performing a smudging ceremony. Bottom: Weston's photography installed on the second floor. Artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez helped with installation. Lucy Gellman Photos.

It’s the child’s gaze that pulls a viewer in, that look of sweet, intense concentration that is far beyond his years. Brows furrow. Eyes swivel forward. His little chin is so square and serious beneath that still-baby-face. His long curls blow in the wind, and he looks right at home. When his left hand reaches up to hold two fingers of his mother’s hand, a viewer can feel their whole heart squeeze in their chest.

The image is one of over a dozen that anchors Prayer Ties, a new, permanent installation from artist Kim Weston about what it means to be Black and Native at the Arts Council of Greater New Haven on Audubon Street. For the artist—a photographer, educator, and mother of six who is Black and Mohawk—it caps off a year of personal and professional growth across the city.

In the past 12 months, Weston has launched and taught her first Focus Fellowship program in photography, installed work at the Arts Council and at BLOOM, and continued to build out Wábi Arts (formerly Wábi Gallery), a collaborative and educational home for artists in the heart of downtown. In particular, she is dedicating time, space and resources to practitioners who have been and are still historically silenced, overlooked, and underrepresented.

“This work needed to happen,” she said in a recent interview at the Arts Council’s offices at 70 Audubon St. “I needed to not just talk about the Native side. I needed to bring in the Black side of who I am and talk about that part. Because we’re [Black Natives] not necessarily seen. We’re on the Pow Wow circuits. People see us, but there’s not many stories about us. I needed to show a visual of it.”

Both Prayer Ties and Wábi’s inaugural Focus Fellowship program—which feel tethered to each other—have been decades in the making. Growing up between Philadelphia, New York City and South Carolina (read more about that here), Weston didn’t often talk about her Native ancestry with her family; only her grandfather ever mentioned it. Then in her twenties, while studying photography, she went on a vision quest. She discovered that her power animals were twin hawks, which still appear to her frequently.

“Why am I called to this?” she remembered asking herself at the time. It was the 1990s, and she found herself reading up on Indigenous customs as she worked in photography, picked up painting, and ultimately made the move back to Philadelphia after a divorce. It was an open question mark, there as she deepened her craft.

That changed when she met her wife, Laura Fuller-Weston, at a candy shop in Philadelphia in the late 1990s. As the two began attending powwows together, Fuller-Weston—who is Seminole, and grew up learning to be proud of her heritage—urged her now-wife to claim both of her identities. For Weston, who was already on the journey to taking the light-filled, long exposures of Native dancers that have become her trademark, something began to click into place.

Detail, work in Kim Weston's Prayer Ties.

“For a long time, it's been challenging for me to claim my Native identity—to really claim it inside my spirit,” she said. “I've always known. My people never really talked about it, but it's always been there.”

That was the first sign of what would later become the work behind Prayer Ties. Then several years ago, her phone rang. It was her older brother, who identifies proudly as Native. As a child, he learned to make moccasins and use herbs as medicine from his maternal grandmother. When Weston picked up, he urged her to claim both her Blackness and her Indigeneity.

Weston could hear his wife, her sister-in-law, in the background, echoing everything he said. She could hardly keep her hands still on the receiver as she began to cry.

“The tears started rolling down my eyes,” she said. “I started writing down the names and the history and where we were from. It just made me feel so proud that this work that has been called through my spirit made me feel like I could really hold it and claim it.”

Detail, Kim Weston's work in Prayer Ties.

In Prayer Ties, that identity sprawls before the viewer, the images telling a story in layers of vivid color, black-and-white photographs, bright wallpaper and garnet red prayer bundles carrying tobacco. As viewers enter the space they stand face to face with large-scale photographs from her series Layers Of The Soul. The images, which use long exposure photography to document dancers, make the space feel sacred and propulsive all at once.

In turn, it transforms the second floor of Audubon Street into something much more transcendent than an art gallery alone. A couch and chairs sit around a low coffee table, inviting a viewer to come, lay down their burdens and stay a while. Beneath the furniture, a rug dips into the legend of the “Three Sisters,” a story that points to the use and importance of corn, beans and squash in Indigenous foodways.

Between two elevators on which viewers enter, a vinyl label reads LAND BACK in clean black lettering. It’s a clear, crystalline reminder that the Arts Council, and indeed what is now recognized as Audubon Street, as downtown, and as New Haven, is all on unceded Quinnipiac land. That, in other words, the common land acknowledgement that has become rote at most arts organizations is a start, but no longer enough.

Down a hallway, Weston has installed intimate color and grayscale images of her family, making clear the universes that exist within her one body. Some stop a viewer in their tracks, demanding a closer look as generations stare back. Others are more documentary, chronicling the meeting of old and new, sacred and pedestrian baked into a centuries-long history of displacement. In one, she has captured a sign that reads “Pow Wow with Cheesecake,” freezing the moment in time.

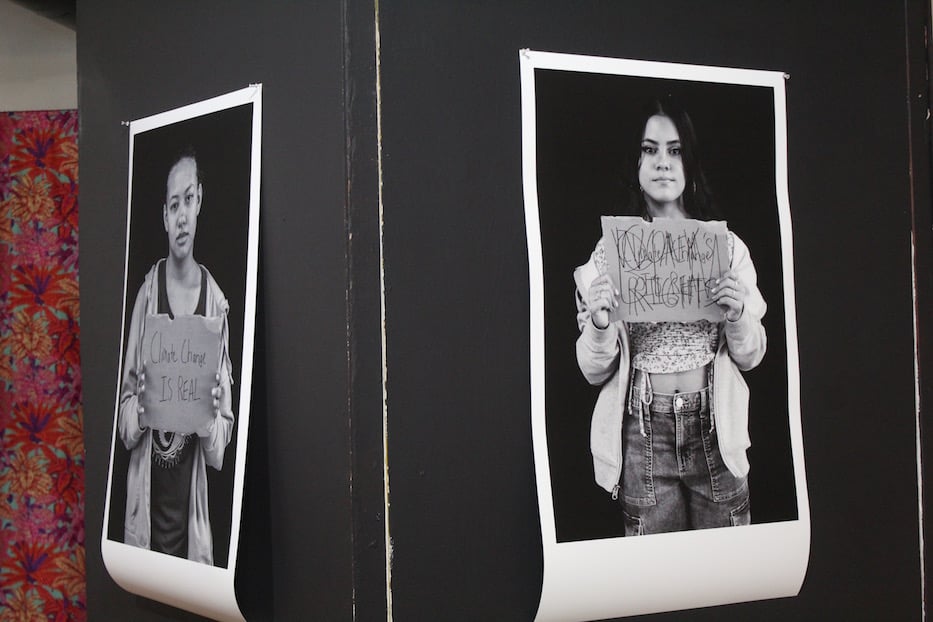

Laila Smith's photography installed at Lotta Studio.

That work dovetails with the Focus Fellowship, through which Weston mentored five young photographers in high school and college from October 2021 through this June. Last fall, she kicked off the fellowship program virtually as the first initiative of Wábi Art, the physical space for which is still under construction on Court Street. For months, students attended weekly meetings, completing assignments as they learned about the history of American photography.

Initially, Weston said, there were ten students in the program. As some of them realized the weekly commitment, that number shrank to five. Those who completed the program received professional DSLR camera equipment, for which Weston had to scramble at the eleventh hour after a donor dropped out. All things considered, she said, she’s thinking of it as a successful first year.

"It was hard,” she said of the program. “It’s hard to translate that passion of what you feel for a medium through a screen. It’s just different.”

Abigail Rossi's self-portrait.

She built a curriculum of photographers who have been giants in her young life, including Lorna Simpson, Dawoud Bey, Carrie Mae Weems, Dread Scott, Sally Mann, Catherine Opie, Bill Jacobson, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Nona Faustine. She also included her own work, which sits at the intersection of photographic practice and self-interrogation.

None of it happened in a silo, she added: she had a team of mentors including Faustine, Zun Lee, Allison Minto, Luciana McClure, Qiana Mestric, Kyle Kearson, Erin Lee Antonak, Natalie Ball and Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez. The group, all teaching artists, spans disciplines from photography to painting to sculpture and multimedia installation.

On a recent Saturday, fellows’ work filled Lotta Studio, photographs peering out from every corner of the Whalley Avenue space. Like the mentors who joined Weston during the fellowship program, photographers Mistina and Luke Hanscom offered Weston free space, helped curate the show, and taught students how to hang an exhibition.

Smith's work.

At the center of the room, Laila Smith’s black-and-white portraits stopped time and space, their subjects staring back out at the viewer. In one, a young person held up a ripped cardboard sign between their two manicured hands, the rough edges of the cardboard stark against their torso and floral-patterned, ruched crop top. From across the room, it looked like a mess of black scribbles.

Only when a viewer came closer could they see half a dozen social justice causes, from Black Lives Matter to women’s rights to the climate crisis, overlapping in black marker. On one hand, Smith summoned the urgency of being young and in a world literally on fire, saddled with crises that an older generation had created. On the other, the artist made an assertion—that the subject was here, ready to fight, and another world was possible. It was both, together that made the photograph worth coming back to several times over.

Across the room, a suite of images from Angel Castro and Jase Upchurch caught a viewer by surprise. At the center of five photographs, Castro took a page from Latoya Ruby Frazier, presenting a portrait within a portrait. Her subject looked out, a second photograph covering their lips.

Angel Castro's work, surrounded by four photographs by Jase Upchurch.

There was something unpretentious there, in the subject’s bare shoulders and upper chest, the rumpled sheet behind them. Castro invited a viewer into an intimate piece of family history, embedded in an equally intimate interior.

Originally, Weston’s prompt to the fellows had been to tell a story of their family. Castro folded multiple generations into one photograph—and continues to bloom as an artist, Weston said. In four photographs around Castro’s portrait, a figure moved through strings of white LED lights, dressed in a flower crown. They posed against a background drenched in blue, their eyes wide and alert inside wire-rimmed glasses. They held up a bouquet of flowers against a purple neon light.

Jase Upchurch. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Upchurch, who asked her friend (and youth arts journalist in the pages of this publication) Atlas Salter to pose as model, played with light, character, and long exposures in interior settings. A rising senior at Sacred Heart Academy, the budding photographer said that her dad was the one who originally inspired her to start visual art. During the Focus Fellowship, she was able to hone her craft, particularly in long exposures similar to the ones that are now a hallmark of Weston’s practice.

It entailed a lot of trial and error, she said. In a photograph close to the street-facing windows, streaks of pink light fell across the image, as if a meteor shower had suddenly touched down to earth, and was taking everything in its path. Behind the curtain of light, Salter stood in full focus, their profile visible even as they moved through space. Upchurch guessed that she took dozens, if not over a hundred, images before she found one she was happy with.

“I feel like it opened up a lot of new things for me,” she said.

Alexandra Guzman, who is now a student at Gateway Community College.

Some of the fellows milled around the room, taking in their classmates’ art—and their own—after months on a screen. At a long wood table, Alexandra Guzman studied the scale of her own work, hanging on the walls in brilliant color beside her. Already, she had spent time looking at a series of grayscale images from her peers, studying the framing of Abigail Rossi’s self-portrait, the shock of red in Smith’s ode to the Pan-African flag.

Then she returned to her own work. In one of her photographs, a bee buzzed toward the white ledge of its hive, its body in crisp focus. At the hive, a number of out-of-focus bees scrambled to get back in, their bodies moving in a coordinated, black-and-yellow buzzing knot. Behind them, an open field and houses stretched out in the distance, marking the space as an urban apiary.

In another, a figure stopped midway through a shed, dwarfed by white beekeeping equipment and boxes on the floor. Guzman was shooting from the outside: hives bloomed around the shed, and houses sprang up in the distance. Unlike the close up beneath it, this marked the setting as an urban apiary. The first time she saw the image, Weston said she couldn’t stop thinking of the work of photographer Gregory Crewsdon.

Detail, one of Guzman's photographs.

A student at Gateway Community College, Guzman praised the Focus Fellowship as unique within the city’s cultural landscape. Because of her schedule, she said it was sometimes hard to show up for weekly Zoom meetings with Weston, but stayed with the program because of her love for photography. When Weston discovered that she was doing work with the Huneebee Project, she suggested that Guzman take it on as a subject.

It became the subject of a series focused on both bees and people, a love letter to an organization that Guzman has called home for three or four years. Because she is so used to tending the hives, her practice often put her very close to the bees, who never seemed to mind the careful, paced clicking of her lens as they went about their business.

Every time she was unsure of something, she touched base with Weston and “we worked it out,” she said. Because she is still with the Huneebee Project, Guzman expects the series to continue. She said that she also wants to keep working with Weston, because the fellowship has been such a positive experience.

“I think the most special part was having a teacher,” Guzman said. “I’ve never had somebody that I can call up and say, ‘let’ meet.’ I learned so much.”

For more about Prayer Ties, Wábi Art and the work that Kim Weston does, check out the above interview with Lucy Gellman, Kim Weston and Babz Rawls-Ivy on WNHH Community Radio. Thank you to our content partners at WNHH-P 103.5 FM, the sister station to the New Haven Independent, for letting us share their airwaves!