Photography | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Yale Divinity School | Arts & Anti-racism | Palestine

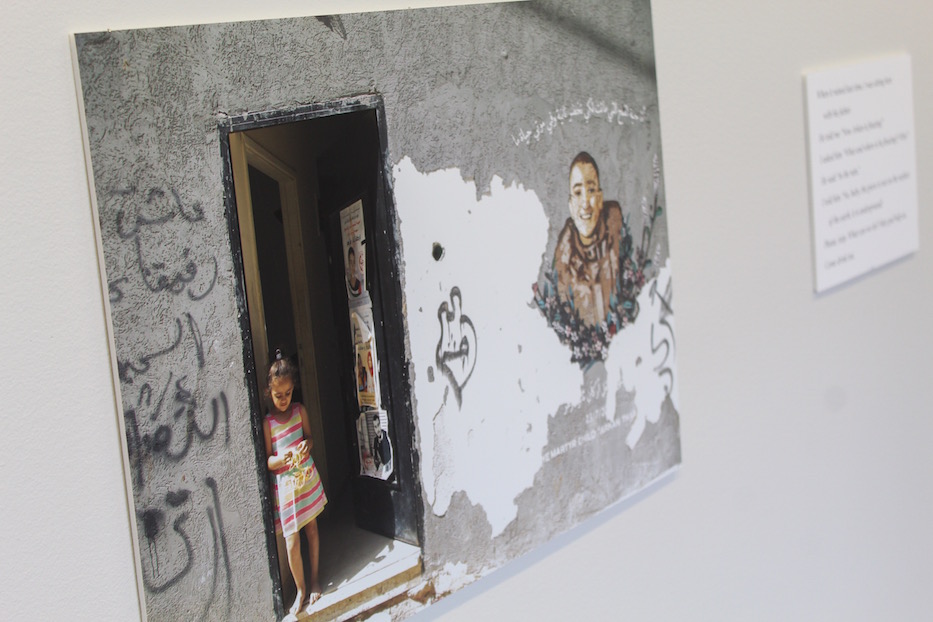

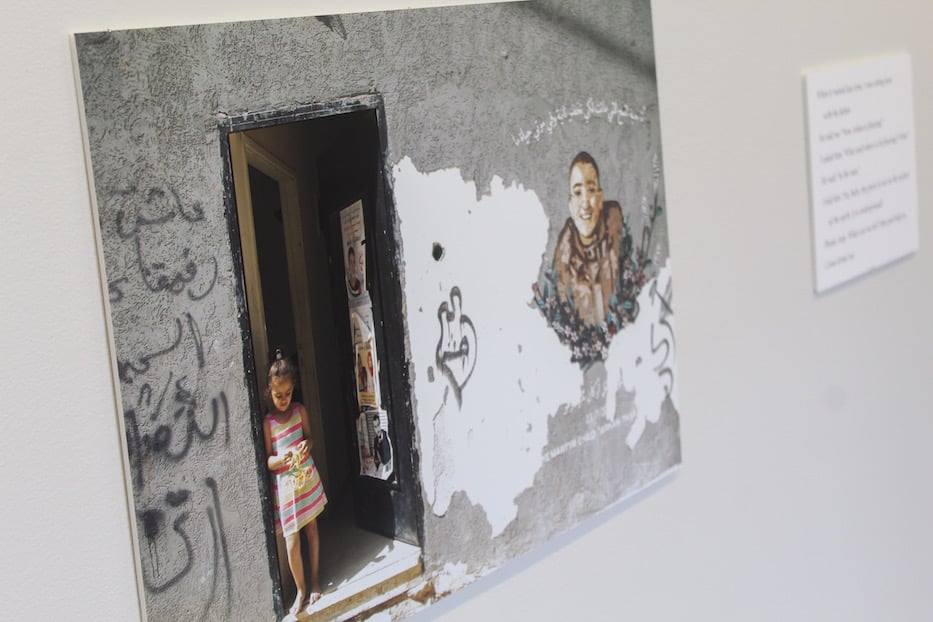

The mural, by Yazan Ghareeb, memorializes Ahmed Mesleh. All photographs in the show are by Margaret (Peg) Olin.

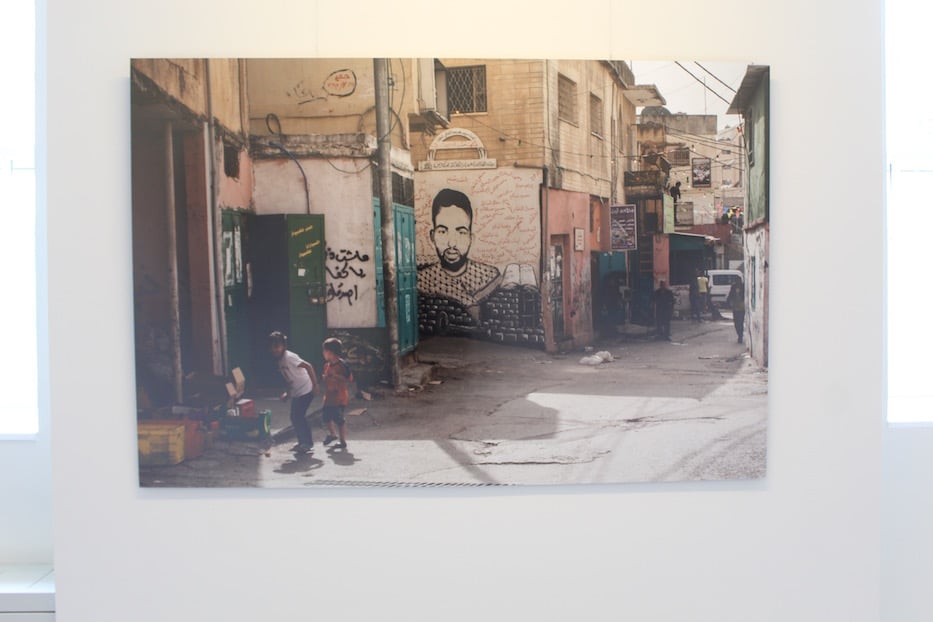

Maybe what catches you first is how little they are, the children who play in the street. The girl is in pigtails, one foot hovering just above the earth. The boy is mid-step, his small hands to his chest. He turns away from the camera. Behind them, the street stretches back, a patchwork of shallow stoops, flat rooftops, low-strung power lines. In the center is a mural of Ahmed Mesleh, who was killed in 2006 by Israeli soldiers.

Around his head, dozens of names float in red ink. All of them commemorate the dead.

The photograph—and its backstory—are part of Gone Like A Sip of Water, a small, deeply affecting exhibition from photographer, art historian, and lecturer Margaret Olin running at the Yale Divinity School through May 31. Through text, photos, and primary accounts, Olin brings viewers halfway across the globe, chronicling life and death in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp on the South edge of Bethlehem. It is a moving, necessary, and profoundly feeling response to the Israeli occupation, apartheid-era policies, and settler colonialism worldwide.

It feels particularly trenchant this month, as Palestinians across the diaspora observe the 74th anniversary of the Nakba, or the forced mass exodus from what is now recognized as Israel. This week, they are also part of a worldwide community mourning Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, who was shot and killed last Wednesday while reporting in the West Bank.

Margaret Olin: “This is not just Palestinian propaganda. This is a mourning ritual. These images are gravestones." Lucy Gellman Photo.

Olin began photographing the Dheisheh Refugee Camp in 2014, while in Israel as part of a conference called “The Photographic Imagination” at Tel Aviv University. During her time there, she traveled with Max Budovitch, a Yale grad who had experience in the West Bank (eight years later, he is now a deputy commissioner for the City of Chicago). The camp was one of the places they visited. She didn’t know it then, but it would be a place she returned to multiple times a year until the pandemic put her visits on hiatus. Three years into Covid-19, it is a place to which she has been glad to return.

Her first time there, “I formed a bond with a young man who took us around,” she said. “The whole experience was a reintroduction to being a photographer.” As she walked through the streets and alleyways, she noticed not only the amount of public art—murals and graffiti sprawl in every direction—but the type of public art. The majority of murals in Dheisheh pay homage to martyrs (Shuhada), or Palestinians killed by Israeli troops, sometimes for infractions as minor as name-calling, being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or throwing a rock or bottle at Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) during frequent raids of the camp. Most of the martyrs Olin saw pictured were under the age of 18.

She also noticed the number of young children, going about their daily lives while surrounded by public art that memorialized a collective, unending grief. When she lifted her camera, it was that dissonance that caught and held her attention. A viewer can see that in many of her images: a toddler carries a small, purple package down an alleyway as a mural of 17-year-old Qusay Al-Afandi rises in the background. The toddler does not look like he can be more than two or three, strutting forward on those little legs. He never knew Al-Afandi, shot and killed by Israeli soldiers in 2008. And yet, it is this place that ties their existences to each other.

Children play as martyrs look on from the walls of the camp.

In a photograph beside it, two children walk down the street, shoulder to shoulder. One covers the other’s eyes, a huge smile exploding on her face. Pink hearts float on the bright, neon green of her shirt. Their joy crackles, bubbles up past the vans parked behind them, a neighbor on his stoop turning away from the lens. In the background, artist Yazan Ghareeb has depicted another martyr, his eyes tired and unblinking. In the foreground, the children continue to play.

“This is not just Palestinian propaganda,” Olin said. “This is a mourning ritual. These images are gravestones. Having these on the street, this is about young lives that are being lost. None of these pictures are about hating Israelis. They’re about mourning people who at least, at my age, who we would call children.”

That ritual is the foundation of Gone Like A Sip of Water, an Arabic expression that means something or someone that is gone instantly and without reason. On a trip to Dheisheh in December 2018, Olin heard the story of Arkan Tahir Mizhar, a 14-year-old from the camp who, in July of that year, had been sleeping over at his grandmother’s home when Israelis raided the camp in the early hours of the morning (police raids are not uncommon; Olin has documented them in her work).

Arkan rose, and tossed a rock at an Israeli military vehicle as forces were leaving the camp. In return, they shot him in the chest. His cousin, 17-year-old Hassan Mizhar, was shot and paralyzed in the same raid.

Arkan was the 31st child—a term that Olin uses without hesitation—to die at the hands of the IDF that year. “His death was both sudden and pointless,” she writes in an accompanying exhibition label. By the end of the year, that number would be almost 60 children.

Arkan's youngest sister in the doorframe.

Olin learned about his death when she met Om Tha’er, the 78-year-old grandmother with whom Arkan had been staying the night that he was killed. Standing on her stoop, Om Tha’er told Olin the story of the young man’s life—and his sudden, unfathomable death. Beside her, a new mural of Arkan adorned the side of the house. In the piece, he smiles, his face full of light. His cheeks still have that young roundness to them. A swag of laurel, studded with tiny, bright flowers, stretches beneath him.

In the majority of Olin’s photographs, Dheisheh’s children do part of the visual storytelling. In photographs of Om Tha’er’s home, a small girl in a striped, technicolor dress stands in the doorway, a toy hanging between her hands. She leans against the frame, sun falling on her shoulders and bare right foot. This is Arkan's youngest sister, Olin explains in an accompanying leaflet. Beside her, Arkan is forever 14. What strikes a viewer instantly is how young both of them look, now suspended on two sides of an increasingly heavy and porous veil.

“A theme that I have written about has been the relationship of children to these images,” she said, standing in front of the picture. “What kind of childhood is that?”

From a leaflet that accompanies the exhibition: On the door to Om Tha’er's home are displayed memorial posters for her two grandsons, Arkan Thair Mezhir and Sajed Mizher, as well as a poster for her severely disabled grandson, Hassan.

In a reflection of a generosity Olin has come to know at Dheisheh, Om Tha’er invited her in for tea multiple times, first in December of 2018 and then on a second trip six months later. Initially, Olin declined. She made her way around the camp, documenting scenes that placed life and death constantly alongside each other. She later wrote that that moment, and the invitation to tea, crystallized something she’d long been feeling.

“In seeing the life of the young people in the streets lined with murals of martyrs, I realized that I was also anticipating some of their deaths,” she wrote.

That sense became even more acute when she returned to Dheisheh six months later. On that trip, Olin learned that Arkan’s cousin, the Palestinian medic Sajed Muzher, had also become a casualty of Israeli forces in March 2019. In the months since she had left the camp, Muzher had begun staying with Om Tha’er at night. In the early hours of March 24, he and fellow medics went to provide help to Palestinians injured in a raid. While providing first aid, Israeli forces shot him in the abdomen. At the time that he died, he was wearing a reflective vest that marked him as a medic.

Arkan's sister sits beneath a mural of her brother by the artist Omar Salim. Olin said that she does not think the artists would choose to depict martyrs as their first choice of subject matter, but are not in the position to refuse.

The conversation that Olin ultimately had with Om Tha’er, and the ongoing relationship that has grown out of it, is the heartbeat of the show (the title, Gone Like A Sip of Water, comes from her reflections on her grandson). Along the wall, snippets of dialogue float in between photographs, telling the story of a community’s grief in short, intimate anecdotes. In one, Om Tha’er recalls sitting with Arkan’s father, watching the rain outside of their home. His father turned to her, and asked if his son was floating in the rain. The words reveal the poetry and madness of grief.

In another, she recalls a jarring visit from “Captain Nidal,” an officer with the Israeli Security Agency known as Shin Bet. He demands to see Arkan’s father, who posted a song memorializing his son on Facebook. In the exchange, written in neat, italicized black text, a viewer can feel the levels of control, paranoia, fear mongering and erasure that go into subjugating an entire group of people because of their nationality.

So too in a cluster of text and photos that describe an effort to start a little free library program in the camp, thwarted when Nidal found out and demanded to know more about the project. Of the three friends who started the program, one was ultimately arrested. Another, 21-year-old Raed al-Salhi, was shot dead at close range during an early morning raid of the camp. In Olin’s photos of the camp’s community center, the viewer is aware of their absence. There’s a sense that they should be here, holding another meeting of their book club, planning for the future.

Paired with the photographs, Olin’s use of text makes clear the ongoing, deep and multi-generational trauma of a forced exodus. None of it feels extraneous or pushy, as if the artist has an agenda and is trying to push it on her viewers. Nor does it feel like disaster porn, where she has parachuted in, gotten her shot of trauma, and left. If anything, it leaves one wanting to learn more about the camp and its long history. Since it was first built in 1949, Dheisheh has grown to house over 15,000 residents.

In their conversations over tea, Olin learned that Om Tha’er herself had been forced from her childhood home, a Palestinian village named Khuldeh that stood in what is now known as central Israel. After Israeli settler-colonialists drove people from the village in 1948, they established the settlement Mishmar David in its place. She was six years old.

In her work, Olin does not ever shy away from the complexity of the Palestinian liberation movement. On the other end of the same wall, two boys ride their bicycles around a bend, rising up on the handlebars as they pump their feet. The tires kick up dust; the boys look as if they are the sons, cousins, siblings, grandchildren viewers know. Around them, faces stare back in every direction, rendered in black and red spray paint with thick Arabic scrawl.

In a handout that accompanies the show, Olin explains that these are canonical figures in the liberation movement. There is Wadie Haddad, a hijacking strategist and former leader Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) who died of cancer in Germany in 1978. Close by is PFLP hijacker Leila Khaled, still living today, and the cartoon character Handala, a refugee child with one hand bound, the other rising. Its artist, the cartoonist Naji al-Ali, was assassinated in London in 1987.

Over eight years, Olin’s time in Dheisheh has solidified a belief system that long predates the work. Born and raised outside Chicago, the artist is soft-spoken, with kind, alert eyes and a halo of white curls. Not a full three minutes into a tour of the show, she called the Israeli occupation “an egregious sin” and was quick to talk about ghettoization and apartheid from the South Side of Chicago to the West Bank (“what else are you supposed to call it?” she said incredulously).

There’s an openness about her that flows through her stories, and into her photographs. On a visit to Al Arroub, an ostensibly dangerous refugee camp in the Southern West Bank, Olin arrived to find that her guide was not waiting for her. When he did not show up, she went in by herself. She soon found that “I was really in great danger … of having too much caffeine.” Neighbor after neighbor invited her in for coffee, until one ultimately found her guide.

And no wonder: she’s been thinking about this land for decades. Her own political awakening came in 1967, during the Six-Day War between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon. At the end of it, Israel laid claim to the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank and East Jerusalem. Twenty thousand Arab soldiers were dead. Over a decade later, she would find herself there on her honeymoon, which happened to coincide with the 1982 Lebanon War.

“There was kind of this, ‘All these territories—now what?’” she recalled of that moment in 1967.

Gone Like A Sip of Water feels like an extension of that question—Now what?—which she has been asking over and over for years. Through the images, she asks viewers to check their understanding of refugees, of Israel-Palestine relations, of what it means to be an impoverished place, and who or what made it so. It’s in the blur of a young girl’s body as she runs across a sloped, narrow street, two hijabi women talking down the street.

It’s in the child who hangs at the far left of a frame, as the faces of two teenage martyrs loom large over the image. It is in a portrait of Om Tha’er that does not picture her at all: a single glass teacup, placed to the left of a serving tray and rubber-tipped cane. The girl in the technicolor dress sits in the background, her knees pulled to her chest.

This month, she is returning to the camp again, ready to continue telling the stories of the people who live in the camp, and the people who die there too. Despite or maybe because of the very nature of her work, Olin said she does not feel optimistic about the potential for dialogue going forward. It's not stopping her from forging ahead.

“It’s really depressing, and it seems to be getting worse,” she said. “I don’t know how this is going to end up.”

Gone Like A Sip of Water runs through May 31 at the Yale Divinity School, 409 Prospect St. in New Haven. Follow Margaret (Peg) Olin’s work on her blog, Touching Photographs. A book about her work in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp is forthcoming.