Dwight | Immigration | Politics | Arts & Culture

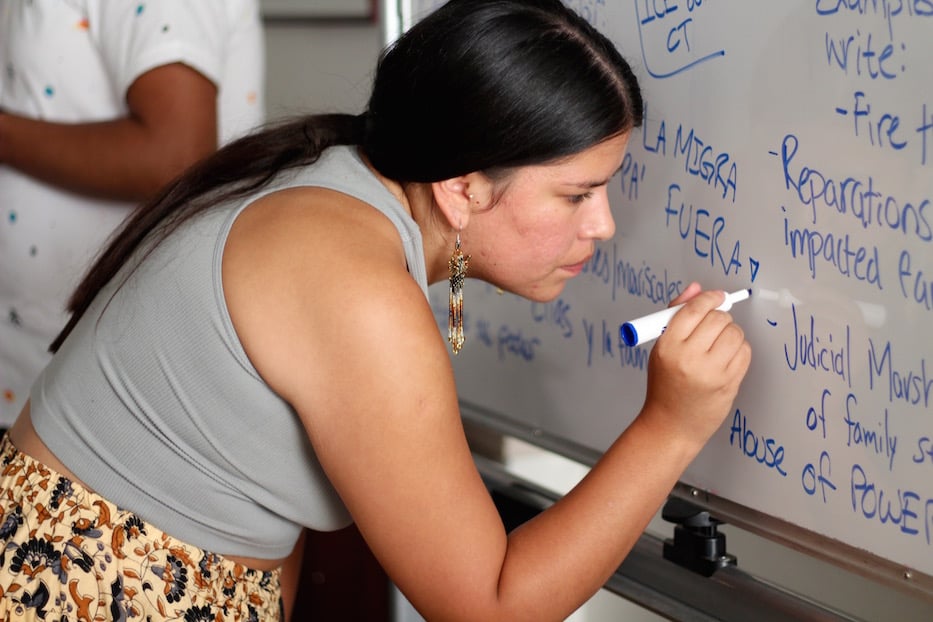

| Vanesa Suarez suggests slogans for the signs. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

At first, it was just a blue tarp covered with brushes and a few bright globs of paint. Then poster board joined the action, with a blur of hands and bodies scrambling for new colors. Words bloomed across each: La Migra Pa’ Fuera outlined in black, yellow and red, the first letters of the word STOP in red and white, a trash can filled with the letters ICE. A rosy-snouted pig peeked out under its brown cap, surrounded by two tiny flames and the words Fire The Marshals.

That was the scene Thursday night at the New Haven People’s Center, where art making has become part of an organizing effort to get Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers out of Connecticut courthouses by asking state judicial marshals not to cooperate with the federal authority. The call for painting comes before next Wednesday, which marks the beginning of an “ICE out of our Courthouses!/La Migra Fuera de las Cortes!” campaign, set for 8 a.m. outside the Meriden Superior Court.

| Jesus Abraham Morales Sánchez. |

The campaign is a joint effort of the Connecticut Immigrant Rights Alliance (CIRA), Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), Connecticut Students For A Dream, Hartford Deportation Defense, Make The Road Connecticut, the Connecticut Bail Fund and Immigrant Bail Fund. Its timing comes roughly six weeks two before October 1, when new legislation for Connecticut’s Trust Act is scheduled to go into effect. The legislation, the product of two bills that passed in May, restricts the ability of state and municipal law enforcement and court officials to cooperate with ICE.

“There are so many people that are being impacted by what’s happening under ICE,” said Vanesa Suarez, who works with the Immigrant Bail Fund and organized the event. “Through art, everyone can express their message. Their personal pain or anger, or what it means to be fighting in community."

“Especially at a rally, there’s a lot of people that walk by, and that drive by,” she added. “When we are conveying what is happening, through a poster or maybe a banner or cloth, it gives power to people who otherwise feel very much silenced.”

According to several immigrant rights activists, state judicial marshals routinely comply with detainer requests from ICE, which activists see as a violation to Connecticut's Trust Act and blow to the state’s judicial system. In the past year, that has included marshals overriding state pardons and rulings from Connecticut judges to release immigrants from custody. In several instances, marshals have informed ICE of immigrants' whereabouts, held them for several hours and released them into ICE's custody.

While the most recent legislation puts new restrictions on law enforcement and court officers' ability to detain immigrants, it does not go into effect until October 1 of this year. Until then, judicial marshals are abiding by the original act passed in 2013, which gives law enforcement and court officials the right to detain immigrants if they are subject to a final order of deportation or removal by a federal authority.

With the new legislation, “they [marshals] could stop now if they wanted to,” said Suarez. Melissa Farley, executive director of external affairs for the state’s judicial branch, said that marshals must continue to follow the 2013 legislation until October 1.

| Eric Cruz López. |

“We’re following the law, and the law right now has seven criteria that everyone has to apply, including judicial marshals,” Farley said Friday by phone. “The judicial branch follows the law. The legislature made a decision that this would take effect October 1. On October 1, we will follow the new legislation.”

Back in the People’s Center, a spirit of protest was coming to life. On a dry erase board at the front of the room, Suarez drew a list of slogans that protesters might use, outlining La Migra Fuera! in a spiky circle near the bottom. Eric Cruz López, an educator with Connecticut Students For A Dream, pulled up a step-by-step guide on how to draw a garbage can, which he started outlining in black and white.

At the lip of the can, he stenciled out the acronyms for Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). He said he planned to paint them in red, white, and blue, as if they were being thrown into the can.

A statewide immigrant rights advocate, López said that the workshops give him a chance to flex his artistic muscles while also channeling a lot of the frustration he feels. While he does not make art in a professional context, he said he's enjoyed the act of painting since he was a kid.

“I feel like I was an aspirational artist,” he said. “So I love doing this. I get to sit with my friends, hang out, talk shit about ICE. It’s nice to have something tangible.”

| Erick Sarmiento and his 11-year-old son Kai worked on two poster. |

Across the room, Erick Sarmiento and his 11-year-old son Kai worked their way through a small pile of green, black and white poster board, writing messages addressed to ICE on each. A member of ULA, Sarmiento said that he sees sign making as intertwined with protest, and a way to teach his son about social justice.

“We enjoy painting,” he said. Kai nodded eagerly, busting into a huge smile.

As she inspected the posters, Suarez said the workshops double as a chance for her to collect herself and prepare for whatever action may be next. In the past weeks, she said she has been reeling from news about deportations in the state and in the country, including a case in Stamford where a woman was released by a judge, then held by marshals for three hours. Suarez recalled screaming and crying with the woman's family as ICE officials picked her up.

“This works takes a lot out of you,” she said. “We have a lot of losses. And big ones. We have some wins, but more times than not ICE is taking folks away. I think emotionally, I’m very angry. I’m very much in pain. But I think that when I lead these art workshops, a part of me steps outside of that anger, and I don’t feel so powerless. I feel like I’m shouting out whatever I feel.”

“It is that evil behavior, that violence, that we want to call out,” she added. “We’re gonna keep doing it until we get them to stop.”