Dance | International Festival of Arts & Ideas | Arts & Culture | Disability justice

The company in Heidi Latsky Dance: D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. The work ran last Wednesday and Thursday at the Iseman Theatre as part of the International Festival of Arts & Ideas. Kamini Purushotham Photos.

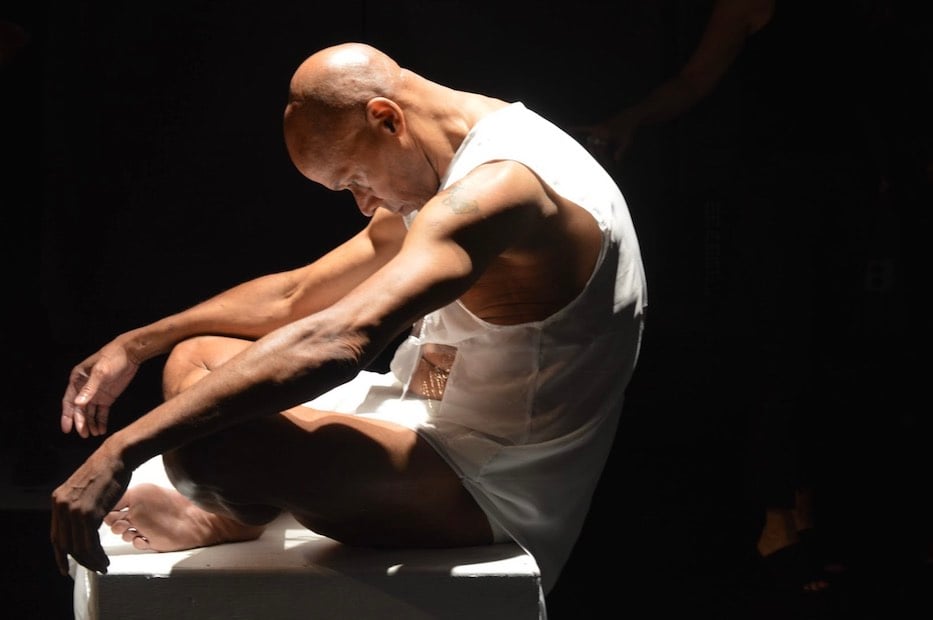

Dressed in a semi-sheer white tunic and matching shorts, the once-frozen man suddenly moved, wheeling around the perimeter of the square of light illuminating him. Sliding out of his wheelchair and onto the stage, he flowed rhythmically to the music, his movements fluid. Returning to his wheelchair, he danced, momentarily, with the device itself before sitting down. Then he moved upstage, abandoning his wheelchair altogether. It remained there for the rest of the show.

The man is Donald Lee, one of 16 performers who took the stage at the Iseman Theater last Thursday for Heidi Latsky Dance: D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. The performance, part of the International Festival of Arts & Ideas, featured dancers of all abilities as well as those with other marginalized identities. In the production, both dancers and company founder Heidi Latsky explored the relationship between the viewer and the viewed—celebrating, rather than ostracizing, the bodies in the spotlight.

“There’s this idea that, by being very still, people who are not used to looking at certain people have the opportunity to really look and experience each dancer as long as they want,” Latsky said in an interview after the show.

Dancer Donald Lee, who on Wednesday joined Latsky for a panel on disability justice on the Green. Kamini Purushotham Photos.

D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. evolved from a prior project, On Display, in which performers remained fixed for the entirety of their performance. That show has been ongoing since 2015, including as a 24-hour Zoom performance during the Covid-19 pandemic. During it, people from across the U.S. joined the virtual meeting throughout the day to participate in the show.

Annually, Latsky also takes a group to the United Nations headquarters to perform it for International Day of Persons with Disabilities. She now has “over 30 countries” across the globe participating in the work, she said.

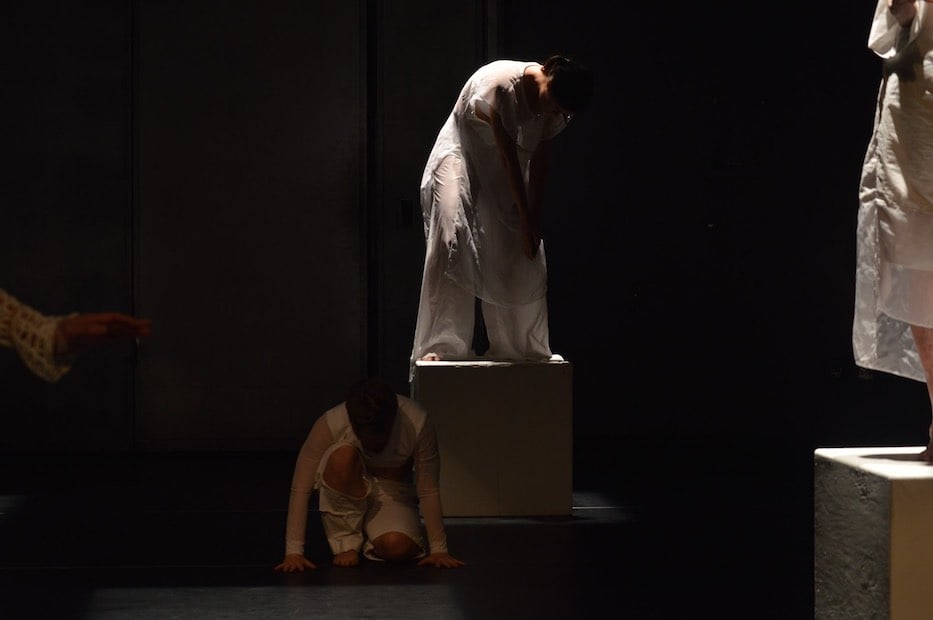

D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. took it a step further, combining Latsky’s artistry with immersive technology. As guests trickled into the theater last Thursday, Arts & Ideas staff invited them to peruse the hall of motionless performers, which Latsky referred to as a “sculpture court” in an interview after the show. Performers stood under spotlights shining down from above, directly on the floor or elevated on white blocks, each holding a static stance.

As guests roamed the sculpture court on Thursday, an audio recording identifying each dancer played, with characteristics like sex, race, age, and height along with details of their physical abnormalities like “arthritic hands,” “awkward gate,” and “upper torso twisted.”

Kamini Purushotham Photos.

Eventually, the audio descriptions of different performers began to overlap, a discordant cacophony evocative of the overwhelming nature of social conventions for those outside the status quo.

Prior to the house opening, guests received wired headphones and could download the Heidi Latsky Dance App, which included audio recordings from each dancer describing the show’s significance to them and glimpses into their lived experiences. On a second walkthrough, the audience heard not objective physical descriptors from an unnamed, toneless voice, but firsthand accounts from the performers themselves. This gave performers the chance to show the audience, and each other, who they were.

“When I’m on display, I feel emotional,” said dancer Desmond Cadogan in his audio bite, “I feel strong and vulnerable.” That duality came through the show’s bold conception, emotionally intimate duets, and stark yet unified musical shifts. Standing upon a platform that accentuated his tall frame, Cadogen gave a stirring performance, juxtaposing his imposing physique with gentle gestures and pensive poses.

“I often feel, that a person, whether a friend or a stranger, can’t even begin to know me until they’ve seen me in performance,” said dancer Meredith Fages in her recording. Latsky’s choreography for Fages included duets with various other dancers, who together moved in tandem, gracefully shifting their weight to lift, spin, and embrace each other in dual displays of tenderness.

Kamini Purushotham Photos.

For dancer Roxanne Young, the performance involved “trying to get to the deepest part of one’s soul.” Throughout D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D, both the collective and the individual became irrevocably intertwined, each one dependent on the other. Dancers had solo choreography, but the show culminated in the collective’s collaborative dancing, wherein multiple performers moved at once, not in sync, but in harmony.

Latsky was inspired to create performances like On Display and D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. after a conversation with a museum curator who saw a video of one of her shows that heavily featured disabled performers. According to her, the curator became distraught after watching it, ashamedly confessing that, while he found the missing-limbed sculptures in museums inherently beautiful, he couldn’t see the disabled performers in the same light.

That perception is what Latsky said she hoped to subvert with D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D, where she presented a wide-range of people as what she called “ideal models.” This framing invited her subjects to liberate themselves rather than confining them to the societal perceptions they were accustomed to. These “sculptures,” Latsky said, “are live people that implode and reform.”

“Some of the performers have been dancing with me for 20 years,” she continued. “Others I met at different events.” Rather than a traditional auditioning process, Latsky had prospective candidates call her. After that, they sent in a video, and, if she was still interested, she brought them into her studio to rehearse.

Kamini Purushotham Photos.

“I’m looking for unique movers who own their own physicality,” Latsky said.

Throughout the show, performers did just that. Take Caitlin Knowles, who said in their recording, “I love the idea of being able to be seen for who I actually am and what I experience rather than submitting to the social pressure to perform what’s expected of me.” In D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D, they danced with purposeful movement: sweeping arm motions and undulating bodily twists.

In Lee’s audio clip, he ruminated on how his disability’s visibility affects how others perceive him. “[I’m] anonymous […] unless I have my legs exposed,” he said. “Then I become a disability, not a disabled person, but a disability.” On Thursday, Knowles and Lee, along with the other dancers, claimed authority over their own identities.

The dancers’ all-white wardrobe, reminiscent of the ancient marble statues that the aforementioned curator spoke of, was a testament to the togetherness and collaboration central to the show. Still, each outfit varied: some featured loose-knit cover ups layered atop each other, while others included intentionally-placed cutouts. Performers decided for themselves what they wanted to conceal and reveal to their audience.

Kamini Purushotham Photos.

In the second half of the performance, the musical shifts intensified, sometimes switching to scores including various instruments overlapping, much like the overlapping audio descriptions that played before the show began. Near the end of the performance, that audio returned, playing alongside the music. Simultaneously, the dancers grew louder, the sounds of their footsteps and their breathing becoming part of the audio-visual experience.

Latsky noted that although the show has been fairly consistent since its genesis, every time she revisits it, “little things change.” While Thursday’s performances featured a cohesive score, Latsky has experimented with the show’s music in past productions.

“I actually had rap,” she said, mentioning her inclusion of music from the Hip-Hop duo Four Wheel City, both wheelchair users. That felt too disjointed, though, so Latsky asked one composer, Chris Brierley, to score the entire performance instead.

Through innovative choreography, powerful music, and enlightening recordings, viewers were invited to gaze upon the performers, not as objects of ridicule, but as embodiments of beauty. Latsky’s dancers were not quite like those lifeless statues with missing limbs, though. Rather, they came alive as they danced—human and complete.

“Every audience member has to find their own message,” Latsky said of the show. To her, the performance was about “everyone coming together in a common space from different backgrounds with different physicalities and different experiences and working really hard, together.”