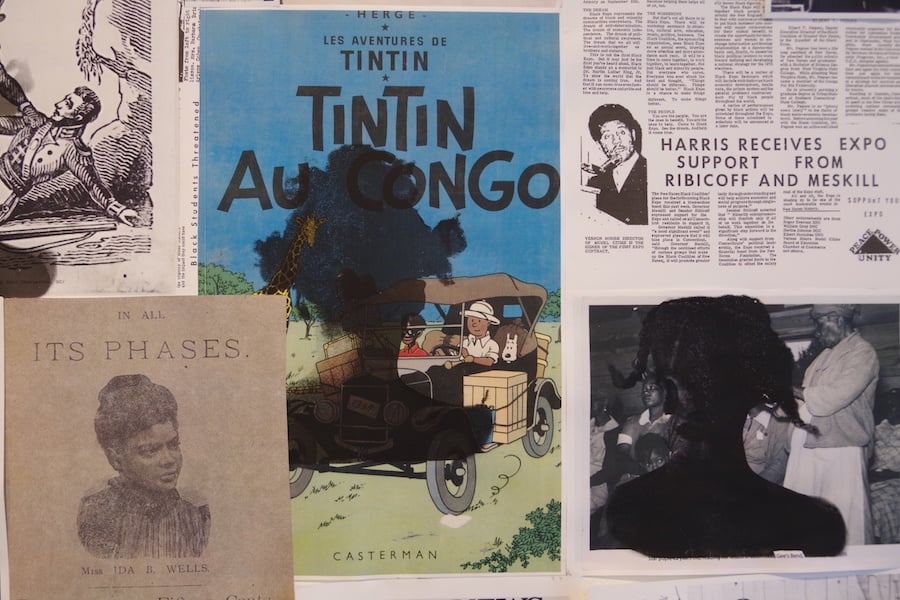

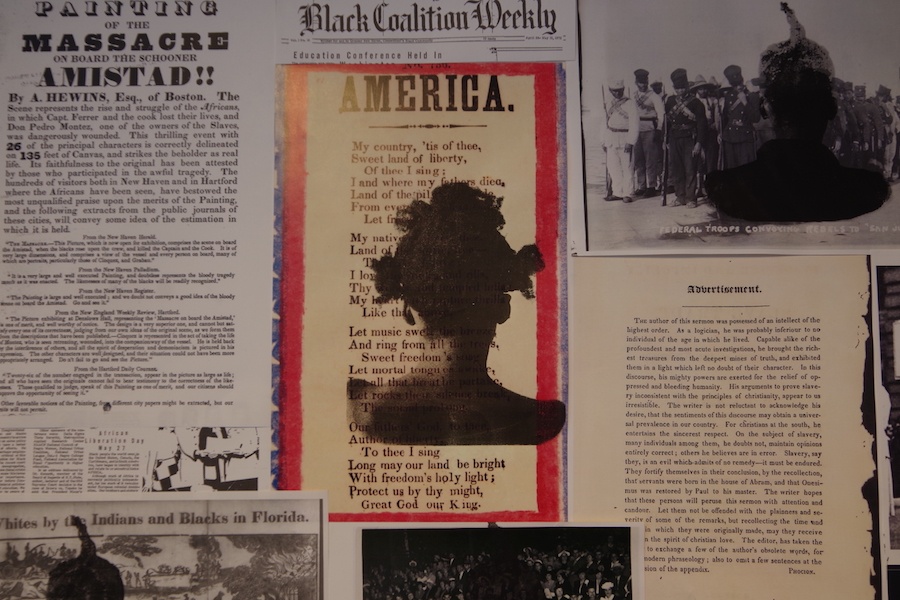

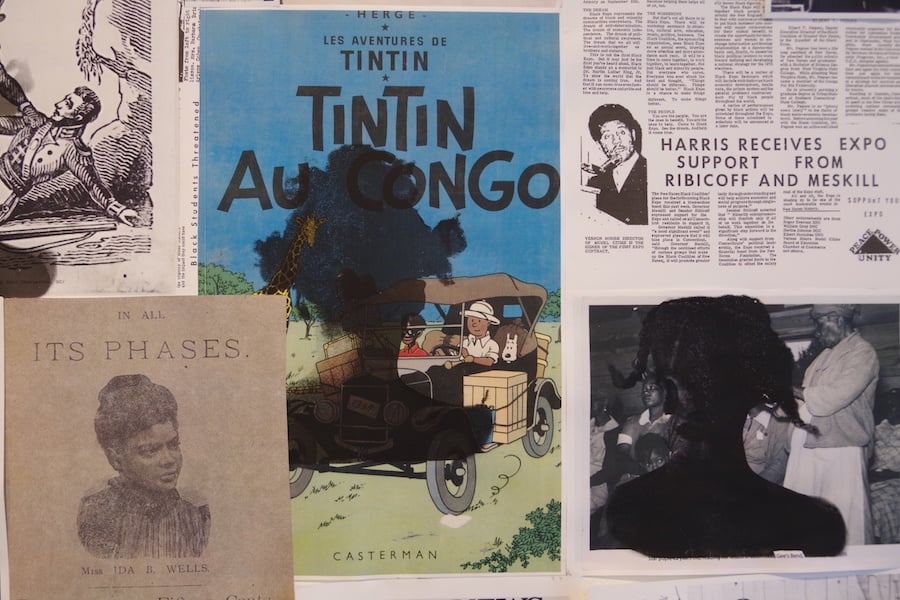

| A detail from Adama Delphine Fawundu’s In the Face of History. Leah Andelsmith Photo. |

The first thing to catch my eye is the hair—braids, and ponytails, and puffs. It’s an image of a woman’s head and shoulders that looks almost flat, as if it was created by a stencil and black paint. But it’s a screenprint, not a stencil, which gives more nuance—the shape of her ear, the light shining on the nape of her neck. She’s facing away from the viewer. In the background, a newspaper bearing the headline “Truman Wipes out Segregation in Armed Forces” is in bold, black letters. There’s a movie poster for “Clansman, or Birth of a Nation.”

Adama Delphine Fawundu’s In the Face of History is just one work featured in Artspace New Haven’s new exhibition In Plain Sight/Site, running through March 2, 2019. Curated by Niama Safia Sandy, In Plain Sight/Site examines the global impact and long-lasting repercussions of the transatlantic slave trade, and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples. It also underlines New England’s role in those systems.

“I am driven by a need to venerate and make tangible the hidden stories of those whose backs this world is built upon,” Sandy wrote in Ripple Effects, an essay that accompanies the exhibit. “In Plain Sight/Site is titled as such to invoke the power of place and vision.”

Standing in front of In the Face of History during a press preview last week, Sandy explained Fawundu’s process.

“Every time she travels, she tries to go to whatever archive is nearby to pull documents,” she said. “This time I asked her to engage with the histories of New England.”

| A detail from Adama Delphine Fawundu’s In the Face of History. Leah Andelsmith Photo. |

She pointed to an early 20th century advertisement for the Black Star Line, a steamship corporation founded by Political Leader Marcus Garvey.

“This was the first one I saw, and I said, ‘Can I have a hundred of these?’” she recalled.

Surrounded by in Fawundu’s work, there is a feeling of heaviness—no way to get one's arms around all that history. Some moments are small and mundane, some are world-changing.

An everyday article details a lynching and an advertisement proclaims “The Magnificent Painting of the Massacre on board the Amistad.” Suffragettes march in the streets. Black protesters picket outside a screening of Gone with the Wind. Shirley Chisholm makes a campaign speech.

With a screenprint, Fawundu has placed the Black gaze on all of that history, all the good and the bad, the hard-won victories and the constant indignities. And there’s something empowering in that. There’s an unspoken commentary on each image, a silent judgement passed by the figures. These Black women are in the driver’s seat. The images touch and sometimes obscure the text itself. Fawundu seems to be saying: “I won’t let us be invisible anymore, because we were there.”

| Nate Lerner, Untitled (Devil Town Series), 2018. Archival inkjet print on bamboo paper. Photo courtesy Artspace New Haven. |

The adjacent gallery displays work by photographer Nate Lerner documenting Wethersfield, Conn., a town founded in the 1630s on Wangunk land. Wethersfield prospered by supplying red onions, among other goods, to Southern and Caribbean plantations. Taking a tour of a historical home this year, Lerner was deeply disappointed to find the town’s involvement in the slave trade swept under the rug. And yet, the onion remains a popular symbol for historical Wethersfield.

Upset by what he saw as erasure, Lerner set out to create his own images in his series Devil Town, making black and white photographs that are haunting and full of ghosts. Lerner captured several of the towns many historical warehouses, used to house those red onions, and the resulting photographs are all about texture. The wood is rough and weathered, yet not weak—a comment on the history the photograph captures.

“The whole show is about little things that we don’t think about in the context of what they actually mean,” Sandy said. “We don’t get to choose what we say about what happened. We have to have fidelity to the truth that took place, regardless of the pleasantness… We all have to take up the mantle of truth.”

| Nate Lerner, Untitled (Devil Town Series), 2018. Archival inkjet print on bamboo paper. Photo courtesy Artspace New Haven. |

Sharing space with Lerner’s photographs is New York mixed-media artist Kimberly Becoat’s “High Cotton Series,” collages made with burlap, cotton, muslin, ink, and gold leaf, along with photographs and other materials.

“These are like tapestry to me, even though they are on paper,” said Sandy.

The first in the series has the most right angles: twine interwoven with burlap and muslin. At the bottom there is a plantation owner and an enslaved man with huge bushels of cotton.

In the collage titled Work Song, twine stretches across puffs of cotton like the slats in a wooden fence. A sheet of muslin lies above the cotton, a hole shaped like a keyhole cut out of it. Except it’s not a keyhole, but the silhouette of a woman. In her photo just beyond the hole in the muslin, she’s in a dress and kerchief, standing next to a bushel of cotton.

The muslin is no longer whole, Becoat seems to say. Accounts have been reckoned with and the price of a life has been subtracted from the cloth. Below, the woman’s photo appears again and again, cut up into strips and interspersed with gold. There is gold splattered on her skirts and over the adjacent cotton balls. It’s a messy profit, a gruesome fortune.

| Kimberly Becoat, High Cotton Series, 2018. Burned burlap, cotton, muslin, sumi ink, gold leaf, acrylic, collaged imagery on paper. Photo courtesy Artspace New Haven. |

In Capital Gains, the photos of people are replaced by fragments of a historical ledger listing names and the amounts of cotton picked by each enslaved person.

There are so many layers, and the pieces draw the viewer in close to find the details. Some ledgers are cut and some are torn. Most of the cotton is splattered in black or gold, but some is left clean. Some of the muslin is tie-died with black ink, some looks stained from an ink spill. The burlap comes in varying earthtones. Some bare spots of the background shine through.

And in the final pieces, one of which is called Black Blood, the scraps of material are increasingly in tatters and pieces are burned. The feeling of patchwork present in the other pieces dissolves into chaos.

It’s like Becoat got lost in her process in the best and deepest of ways. At Friday’s preview, I could imagine her up to her elbows in cotton balls and burlap and ink and twine, caught in the magic of creation. It’s the kind of play that is not light but profoundly therapeutic and essential to the human condition. The resulting collages read like a cubist view of the cotton trade, interrogating it from all angles and all aspects.

| A still from Deborah Jack's A Salting. Photo courtesy Artspace New Haven. |

Becoat’s series winds its way into the adjacent gallery, a room that Sandy calls “the heart of the show” because it is the location of Deborah Jack’s video installations Untitled (Sea #2) and A Salting. The complementary videos depict waves on the shores of Sint Maartin, the Carribean island Jack calls home.

The sound of crashing waves has a calming effect and can be heard throughout the exhibit, but Sandy points out that the ocean can be both life-giving and life-taking and plays an important role in this history.

“I meant it to be piped throughout the show,” she said about the video’s soundtrack. “I meant it as a grounding element. We don’t get any of this without the sea.”

By “this,” Sandy was referring to the rich and often troubled themes explored by the other artists in the exhibit. James Montford deeply examines indigenous and African-American experiences with genocide. Maya Vivas contributes a visceral depiction of the black body. Tajh Rust re-figures West African ritual masks pulled from the Yale University Art Gallery’s collection. Tariku Shiferaw shows a fascination with the modern shipping industry and the way that black culture is commodified and consumed by the public. And Jocelyn Braxton Armstrong’s unearths her family roots and discovers what it means to “pass” as white.

| A still from Coleman Collin’s Distancing, Determining. Photo courtesy Artspace New Haven. |

In the far corner of the exhibition, Coleman Collins' video installation Distancing, Determining, runs on a loop. But it’s worth it to watch the film from the beginning. Collins gathered footage over three years of world travels and his camera captured Africans and African Americans through out the world—scenes of blackness in diaspora.

There’s a library filled with African and African-American artifacts and archives. Track and field practice. School children clapping and singing as they play a game. Tourists posing in front of the larger-than-life statue at Nelson Mandela Square. A shopping center named Obama Court. A woman walks down an aisle of beauty products, but it’s the Dark n’ Lovely home relaxer kit on the shelf that dominates the frame.

The images are perfectly framed, the colors, figures, and lines of composition all carefully considered. Each moment is a point of intersection on a net stretched over the globe. It made me think of blackness like a web of economics, trade, movement, and culture covering the earth.

| A still from Coleman Collin’s Distancing, Determining. Leah Andelsmith Photo. |

Collins reveals gatherings, landmarks, and heroes; fences, roads, and commerce; transit, boats, and again and again the sea. Finally, we arrive with him to Badagry, the historical site of a major slave port off the coast of Nigeria. We have followed Collins a spiral path through time and space and finally reached at the nugget in the center.

Collins crosses the “point of no return”—where enslaved people would have boarded ships embarking on the Middle Passage—and stands on the beach before the grey, churning waves.

“You really got a hold on me,” he sings to himself as he films. “I love you and all I want you to do is just hold me, hold me, hold me.”

After the film finished, I stepped out into the room Sandy calls “the heart of the exhibit” and I was greeted by the sounds of the ocean, touching all aspects of the space. That act, the physical moment where humans were traded, forced onto boats and taken across the ocean, is the beating heart of this exhibit. And it is the heart that pumps blood through economic systems and race relations in our country and across the globe. These artists have found it. They have put their finger on that moment of trauma and traced the ripple effect it has had in the Black psyche.

I ended up back where I started, in the first room with Fawundu’s work, facing all of that history, the present world pressing in on the other side of the picture windows. How many scenes are there? How many vignettes of black experience? I took a deep breath. I felt like I’d been far, far away.