Institute Library | Arts & Culture

It’s that center eye, staring back like a cyclops, that warrants a second look. Flecks of purple and green surround it, a thick brown eyebrow arching above. Yellowed and pink flesh fill in the forehead, cheeks. Two mouths hang open below, lips bright red and rows of teeth exposed. No words come out.

Patricia Fabricant’s woven paper collages are part of Shelf Life, the latest exhibition from curator-in-residence Martha Lewis at the Institute Library (IL) on Chapel Street. After opening quietly at the end of September, the show runs through Dec. 29. It comprises works in both the upstairs gallery and on the first floor of the library.

At its core, Shelf Life is about stories: whose stories we tell, and whose we forget. Lewis’ vision for the show began earlier this year, in the IL’s musty and sun-flooded Biographies Room. Looking at the tomes around her—and the biographies populating the library more generally—she started to wonder just how many stories didn’t get told, or were told with a heavy revisionist hand.

“I’m interested in how some people get kind of lost, or some people never make it into history,” she said at the opening of the show. “That brings up all kinds of issues about fairness and inclusion and social justice, so I thought it would be interesting to have a show that touched on it.”

“The fact is we all come from somewhere, and everyone has a story to tell,” she added.

In the show, those stories stretch from wall to wall in a variety of media, turning the gallery into a sea of memory, a chronicle of histories retold and rectified. They begin well before the gallery proper—as viewers walk up the IL’s old wooden staircase, they encounter several black and white archival prints, to mark their passage into this world of paying homage.

Immediately, there’s familiarity there: John T. Hill’s iconic prints from 1970’s May Day rally on the New Haven Green, of which there are more upstairs. But also pieces we may not know, including some treasures from the photographer Adger Cowans’ personal collection.

In one—a film still from Cabin In The Sky that stops you in your tracks—Lena Horne leans back on a chaise, legs casually crossed, head turned toward actor Eddie Anderson. It’s not clear if he’s there as Anderson or in character, as redeemable gambler Little Joe Jackson. Back on the couch, Horne fixes her eyes on him and rolls her shoulders back as a smile spreads across her face. But she can’t get Anderson’s attention: he’s turned toward the camera’s lens, shoulders angled, eyes wide. Behind him, Kenneth Spencer leans in, buttoned head to toe in white regalia as The General.

If you’ve seen Cabin In The Sky, you know it’s a film overshadowed by stereotype and convention that still finds joy, that has a particular way of telling its story and remembering its stars. It sets the stage for Shelf Life’s overarching theme: revisiting stories we thought were fixed in the past, and working harder to understand them.

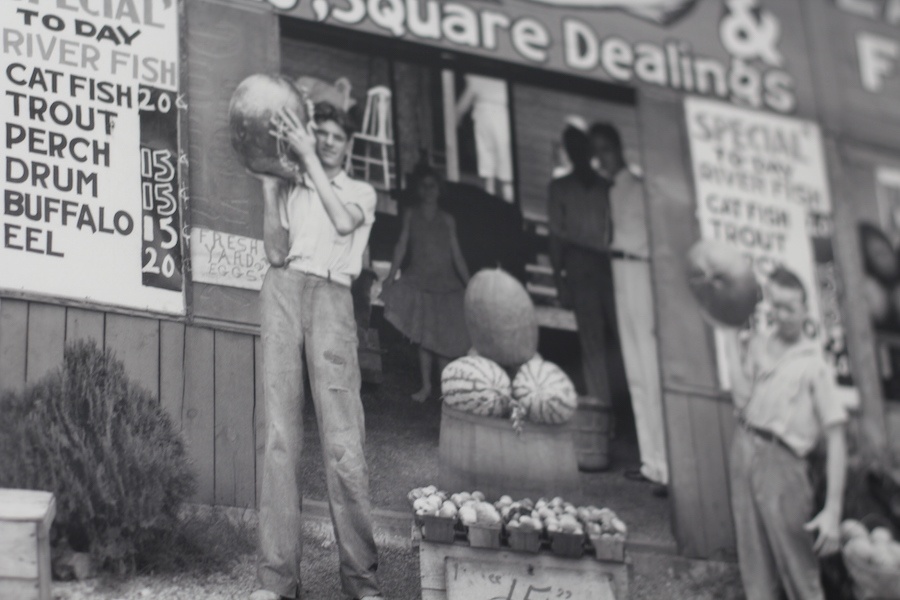

That sense echoes in Walker Evans’ 1936 Roadside Stand Near Birmingham Alabama, as a handful of people gather for the camera. In the foreground, two boys lift pumpkins, the gourds so big they have to shift their body weight around and use two hands until they get comfortable. Further back inside a barn, three people look on, scoping out the situation.

It’s charming—the story they want to tell is one of safety and abundance, of grace and courtesy. Inside the barn, a little girl holds out the folds of her dress as if she is about to curtsy, her little feet placed shoulder length apart. But the image also holds weight: in placing it beside Lena Horne, Lewis levels the narrative playing field.

It’s one in a series of masterful curatorial choices, where she knows exactly what she’s doing. At the top of the stairs, the viewer must stop to take in the full effect of Jean Scott’s 2001 Memory Tags, a hanging, crowded installation of post it-sized portraits that are meant to be worn. Started as a project to memorialize Scott’s mother, who died when the artist was very young, the tags stretch out across the white wall, drawing in the eye. But they also speak to the indexical way we practice memory: smiling snapshots, likenesses that vibrate and double as if they may disappear, and even the inclusion of human hair.

Around them, whole worlds of history unfold. Large cases to one side of the room wink out with Thomas Mezzanotte’s rich tintypes, bold but intimate portraits of New Haveners that include the artists Clymenza Hawkins, Miggs Burroughs, Maryann Ott, and Dexterity Press cofounder Jeff Mueller. On the other side of the case, we return to Fabricant’s collages, a series of woven paper venn diagrams she began after the 2016 presidential election left her in a soup of feelings each day.

Turn around, and viewers are face-to-face with the biographers of our city and our state. On one section of the wall, several of Hill’s photographs bring us back to the New Haven Green almost 50 years ago, during New Haven’s tumultuous Black Panther trials of 1970. Closer to windows that face out on Chapel Street, painter Mary Dwyer has memorialized Mary and Eliza Freeman, pioneers of innovation and entrepreneurship in Connecticut’s “Little Liberia” (modern-day Bridgeport) during the nineteenth century. They beg viewers to take a closer look, whip out the gallery guides or their phones, and look the women up.

They’re not the only women to get a second, third, or fourth look—painter Cristina Sarno has taken on Mamie Eisenhower, Barbara Bush and Michelle Obama in thick, blobby and aggressive oils, Obama striking in her resemblance to one of painter Willem de Kooning’s grinning women. Across from them, Allan Rubin’s fantastical busts of Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Elizabeth Catlett look out at the viewer, bright and lifelike (they have real substance, made of recycled cans).

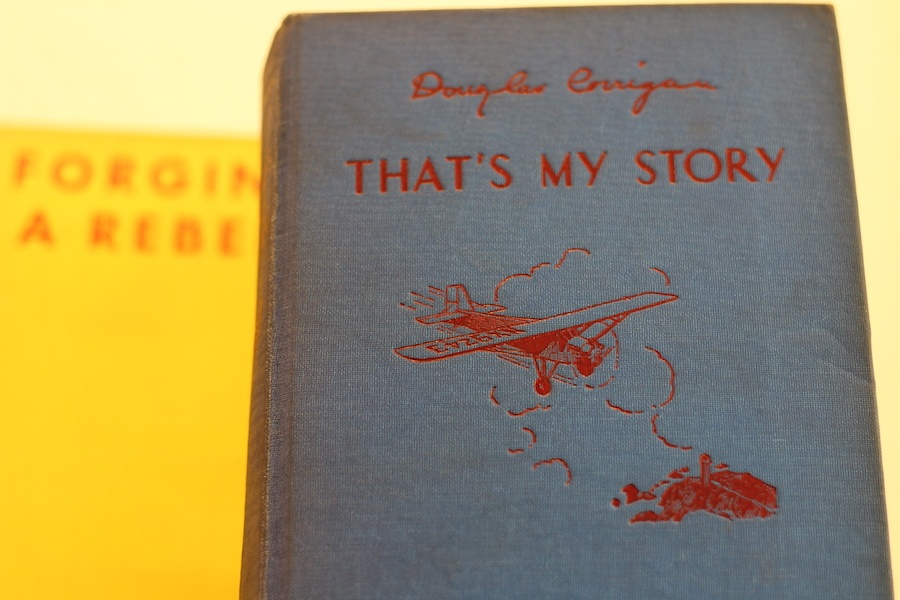

Throughout, Lewis has integrated biographies from the IL’s own collection, their jackets faded and pages yellowing at the tips. They’re full of new names we want to get acquainted with, like the legendary matadora Conchita Cintron. Emma Lazarus' "The New Colossus" marries the theme from its frame on the wall. Downstairs, portrait artist Brenda Zlamany and ECA students Aliya and Sofiya Hafiz have installed hundreds of Zlamany’s paper cutouts, preliminary drawings for her portraits. In each, there’s an untold story just wanting to get out.

In this sense, Shelf Life nails some of the history one doesn’t really get in high school: not the pantheon of great dead white men (although there are plenty of them in the show), but the artists, revolutionaries, and community members who have made this life a thing worth living. It’s simultaneously ambitious and scalable—there’s no sense of it being a complete history, so much as one that amends the record enough to set an example for future amendments.

And Lewis, present in the installation, presses us to ask: How am I remembering? What histories am I telling? Which ones have I left out? And what will people say when I’m gone?