Film | Arts & Culture | Yale University | Arts & Anti-racism

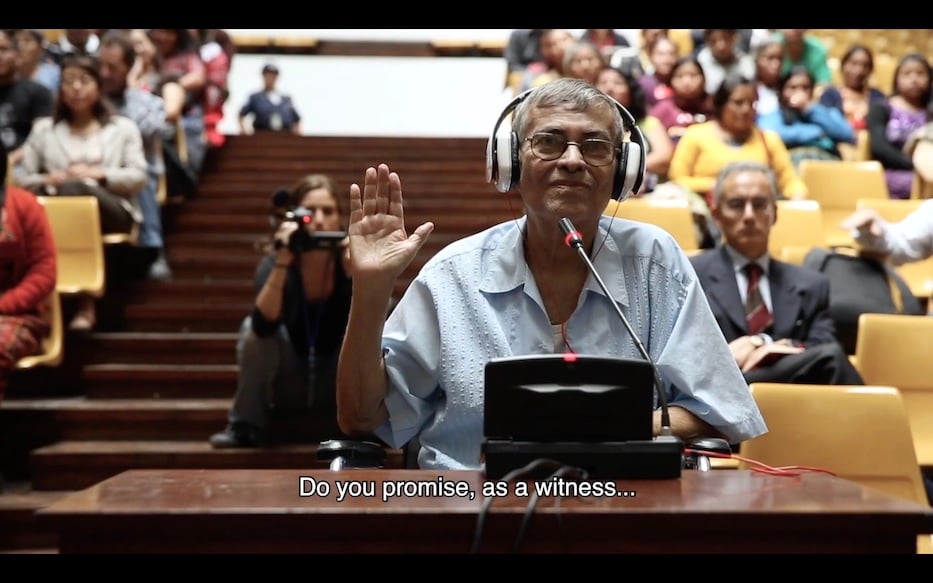

A still from Anaïs Taracena's El silencio del Topo (The Silence of the Mole), a 2021 film from Guatemala.

A Spanish documentarian tries to dig deeper on the story of a beloved Surrealist filmmaker, and finds a tie to his own history in the process. A dark comedy from Puerto Rico makes viewers think twice about planning a wake—and laugh out loud when they may need to most. A snapshot into the abduction of babies in 1980s Peru shows the life-threatening work journalists do to uncover the truth. And in an urban garden that needs protecting in Monterrey, Mexico, a story of familial love becomes a question of who owns the land.

All of those are on tap for ¡Exprésate!, the 13th annual Latino and Iberian Film Festival at Yale (LIFFY), running Nov. 7 through 14 in person and online at the old Whitney Humanities Center and in Yale’s Humanities Quadrangle. The brainchild of Margherita Tortora, a senior lecturer of Spanish at Yale, the festival will bring 70 films from across 19 countries to New Haven. Over 20 filmmakers, actors, and directors plan to grace the city in the next week. All in-person screenings will take place at 53 Wall St.

This year, films come from Puerto Rico, Chile, Cuba, Bolivia, Guatemala, Paraguay, Peru, Mexico, Ecuador, Honduras, Spain and Venezuela among other countries. Tortora is quick to say that she does not do the work alone: the LIFFY team includes Claudia Valeggia, Asia Neupane, Francisco Ángeles, Josh Mentanko, Daniel Vieira, Anthony Sudol, Joy Sherman, Leonardo Mateus, Charlie Mayock-Bradley, and Paola Santos.

Argentine filmmaker Dahlia Fischbein, NYU Professor Tatiana Rojas Ponce, and Colombian filmmaker and animator Miguel Rueda made up the 2022 jury. It is supported by the Council for Latin American and Iberian Studies at the McMillian Center at Yale, the Kemp Foundation, the Progreso Latino Fund and the Slifka Center among other donors. View a full schedule here.

“I think LIFFY has such a variety of films, and of people, that it opens the spectators’ eyes about how diversity can be so rich and fulfilling.” Tortora said in an interview last Thursday afternoon. “And now we’re much more alike than they would like us to think. Right? I think it’s impossible to be racist against someone if you get to know them.”

This year, planning for LIFFY began in March—just months after the Omicron variant had pushed performances, festivals, and in-person events back online. As Tortora and the team planned, they gravitated toward an in-person festival, but kept the hybrid option in mind. Meanwhile, Tortora kept hearing from teachers, students and cinephiles across the U.S., Latin America, and as far as Hong Kong that the virtual component had allowed them to access films they would otherwise never see. So she and fellow organizers struck a compromise: bring back the in-person component, and keep the online one too.

The festivities kick off in person on Monday Nov. 7, with a discussion and screening with Spanish filmmaker Javier Espada. A lifelong lover of filmmaker Luis Buñuel—and now “a world expert,” Tortora said—Espada will join LIFFY for a screening of Buñuel, un cineasta surrealista, a documentary on Buñuel’s life and work that premiered last year at the Cannes Film Festival. The screening, and all in-person screenings this year, will be held at the Whitney Humanities Center on 53 Wall St.

Meanwhile, a whole week of films will launch online, for those who are unable to make it in person. As LIFFY lifts off Monday, they include a night of Spanish films, from a tender, witty short on an 80-year old widow and her small dog (Joseph Oller’s Fils trencats) to at least two takes on the fleeting nature of mortality. They include María Guerra’s deeply existential 8:19, a 13-minute film made this year, and La Masia Reels’ Cohete, which probes the nature of life, death, and filial bonds beyond the veil. Those films will be available for 24 hours after they are first made public.

“We start off pretty slow with the in-person, which is good, because we can savor those few days,” Tortora said. On Tuesday, Espada kicks the afternoon off with a second talk about Buñuel, followed by a night that celebrates documentary filmmaking in Venezuela. Online, viewers can access shorts from Brazil, Portugal and Spain.

The lineup doesn’t remain slow, however: programming Wednesday through Sunday includes panel discussions, lunches, live Q & A sessions with actors and a final awards ceremony from the festival’s jury. On Wednesday afternoon, for instance, attendees can hit an in-person conversation with professors Jorge Méndez Seijas and Oscar González Barreto and with filmmakers Anabel Rodríguez and Andrew Kirschenbaum—and then strap in for a night of cinema.

That evening, Tortora is looking forward to screening on site two new documentaries about Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. The first, Sonia Fritz’ La planificación en Puerto Rico/Planning in Puerto Rico, looks at the failure of urban planning, reconstruction, and U.S. aid in Puerto Rico after Maria’s devastation in 2017. In the second, a 91-minute documentary from JuanMa Pagán Teitelbaum called Serán las dueñas de la tierra/Stewards of the Land, Teitelbaum explores the rise in women cultivating the land in Puerto Rico, the process of which has become a kind of reclamation.

Afterward, Dartmuth Professor Martina Broner and Teitelbaum will be in discussion with each other. That is just the tip of the cinematic iceberg: Wednesday also includes virtual options from Bolivia, Paraguay, Spain, Puerto Rico, Cuba Honduras and Chile, from a portrait of drought in the Atacama desert to the generations of colonial trauma still alive on Honduras’ plantations.

While she is excited for all of the films, Tortora said, she is particularly interested in those that speak truth to power, uncover corruption, and use storytelling to remind viewers of their shared humanity. On Tuesday evening, she is excited to show Nos vemos pronto, a 25-minute documentary by Kirschenbaum about Venezuelan refugees living in Colombia. The filmmaker, who hails from Hamden, will be on site for multiple discussions and question-and-answer sessions.

This year LIFFY also has several Cuban films on its lineup—some of which have become controversial even before hitting the New Haven screen. On Wednesday, Tortora is looking forward to the premiere of Daniel Ross Diegues’ feature film La espera, filmed entirely in Guantanamo, Cuba with a Guantanamo-based crew. Because Diegues is in Cuba, he cannot come to the festival and the screening will be virtual.

It is one of several films by Cuban filmmakers, including Miguel Coyula’s 2021 Corazón azul, Eliecer Jiménez Almeida’s 2021 Veritas, and Eduardo del Llano’s 2022 El regreso de Nicanor. Because del Llano is a Communist, the screening has been so controversial with Cubans now living in the U.S. that Tortora has received hate mail, she said. In some ways, she said, it's a form of validation: she chose to title the festival iExprésate! after watching the rise of censorship in Cuba and across the globe.

Almeida’s Veritas has also already made him something of an enemy, and Coyula is no longer legally allowed to work in Cuba, in part because of his documentary Nadie (No One). The film follows the poet and writer Rafael Alcides, whose work made him a darling, and then a foe, of law enforcement during the Cuban revolution.

That resistance to censorship extends across the weeklong festival, she added. On Nov. 13, the festival plans to show El silencio del Topo (The Silence of the Mole), a 2021 Guatemalan film from Anaïs Taracena that has also been tapped for an Oscar nomination. The documentary follows Elías Barahona, a journalist and member of the guerrilla movement who was able to infiltrate the government of Romeo Lucas García.

Years later, Tortora said, it resonates. She is doubly excited for a talkback with Taracena and CLAIS Postdoctoral Fellow María de los Angeles Aguilar about historical violence in Guatemala. In addition to her work as a historian and academic, Aguilar is Maya Kʼicheʼ and comes from a family of historic activists.

“Now there’s a big problem in Guatemala with repression of journalists and reporters,” Tortora said, recalling the recent arrest of José Rubén Zamora in July of this year. “All over Central America, there’s a repression of freedom of expression. So I thought it was a good title, a good theme for this year’s festival.”

She is also thrilled to be bringing New Haveners several feature films, from Silvina Schnicer and Ulises Porra’s hard-hitting Carajita, which probes the boundaries of race and class between a child and her nanny, to Tricia Ziff’s Oaxacalifornia to Melina León Canción sin nombre (Song Without A Name). The third, inspired by León’s father’s work as a journalist, tells the true story of Peru’s fake maternity clinics, where medical personnel offered free care to women in poverty, and then stole their babies.

The festival may be hard-hitting, but it will not be without laughter and heartfelt storytelling, Tortora added. On Nov. 13, the festival winds down with an in-person screening of Gisela Rosario Ramos’ 2020 Perfume de gardenias, a dark humor out of Puerto Rico in which a grieving widow plans a detailed wake for her husband. The problem is, Tortora said, she does it so well that neighbors ask her to do the same for them. While the director will not be present, there is a question-and-answer session with Blanca Rosa Rovira, an actor from the film.

As the festival moves into its 13th year, Tortora said she knows there are some LIFFY faithfuls in New Haven—but also hopes that some people will discover and fall in love with the festival for the first time. She lauded the students, New Haven Free Public Library staff, fellow educators. and longtime LIFFY fans who have popped out of the woodwork. Among them is Soul de Cuba owner Jesus Puerto, who has been supportive of the festival since its inception as the New England Festival of Ibero-American Cinema (NEFIAC).

“Once you know people as individuals, the stories of people, you become more sensitive to their situation,” she said. “It’s not like ‘Oh! All these hordes of immigrants are crossing our border and they’re all murderers and drug traffickers.’ It's like, ‘Gee, there’s this family in Fresno, third generation Oaxacan. What does it mean for them to be Mexican?’”

“It is showcasing Latino and Iberian culture and the work of brilliant filmmakers in order to educate as well as entertain,” she added. “And make people think. Think, and question what they thought was true.”