Downtown | Institute Library | Arts & Culture

Last Friday's intimate listening group. Jadan Anderson Photos.

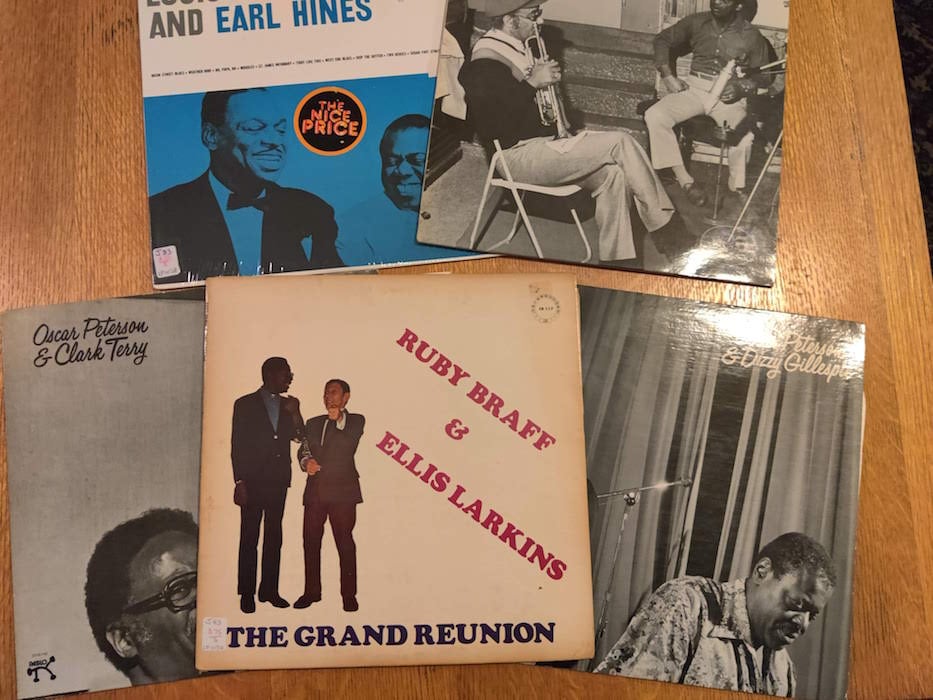

Frank B. Cochran sauntered over to the brown vinyl record player that sits in the Institute Library’s upper room. “Weatherbird”—the famous trumpet and piano duet by jazz legends Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines, respectively—was blaring its final note, a clear C5 on Armstrong’s custom-made Selmer horn.

“Now,” Cochran began. “This is obviously Louis Armstrong. Even people who aren’t familiar with jazz typically guess that right. This song was historically significant in the era of jazz. No one would have conceived of a trumpet and piano duet without some percussion in the background keeping rhythm. But these guys were so familiar with each other’s musical styles that they pulled it off. I figured this would be a good way to start off our night!”

Cochran is a jazz historian and host of weekly Happy Hour Jazz nights—small, bring-your-own beverage listening sessions every Friday from 5:30 to 7:00 p.m. at the Institute Library on Chapel Street. By donation and open to the public, these sessions include a special selection by Cochran of iconic jazz LPs from the Institute Library’s extensive jazz collection, and often LPs from Cochran’s personal collection.

After listening together, discussion about specific songs, jazz music and musicians generally—and anything else, really—ensues.

Frank B. Cochran and Santiago Achinelli.

These jazz nights are presented in concert with and support from Jazz Haven, a non-profit whose mission is to “advance the culture of jazz in Greater New Haven through performances and education.” Cochran, a former Connecticut attorney, enjoys his retirement from law as a member of Jazz Haven’s Board of Directors.

Between records, Cochran gave short expositions about the artists lives and relationships with each other, as well as tantalizing details about the songs on each LP, especially if they were fan favorites. The next vinyl, a series of duets between Oscar Peterson and Dizzy Gillespie, was greeted with anticipation by jazz night’s attendees, which included two young couples, two older couples, a few members of the Institute Library, and Santiago Achinelli, co-host to Cochran for the night.

“These nights started off as bi-weekly sessions,” Anchinelli said. “But I pushed for weekly, and now we’re here.” Achnielli, chief operations officer at My Language Link in Branford, greeted latecomers and passed around record covers to curious attendees.

Peterson and Gillespie’s “Autumn Leaves”—the third song on the record—is a seven-minute long, dizzying flurry of chipper, chromatic-scale melodies and bluesy interludes, reminiscent of a New Orleans “Big Band” sound. The brass and piano take turns supplying the rhythm. The whole song is wrapped up by a crescendo that builds quickly and then settles almost instantaneously into a gentle, major piano resolve. The listeners all took a deep breath, relieved. One attendee laughed and remarked, “Well I’ve never seen autumn leaves like that.”

Jazz music is characterized by improvisation. Especially for musicians, jazz is revolutionary in the evolution of music because of all the sudden changes in rhythm, tone, instrumentation, and tempo. Whereas popular music prior to the emergence of jazz followed more classical principles —a more obvious and consistent beat, strict adherence to a composition, and performance driven primarily by the music—jazz plays with rhythm, improvises a composition, and is primarily driven by the musician.

A person trying to keep rhythm listening to a jazz piece will find themselves pausing to listen to a new rhythm, only to find that once they’ve found it, the rhythm changes yet again, in whatever way the musician fancied. Even more characteristic of jazz music is that the melody line often takes a completely different rhythm than the rest of the instrumentation.

The IL on a recent Friday night.

Like these varying elements that make jazz music jazz, the way people listened to jazz Friday night was different, too. One young couple in the corner of the upper room listened with furrowed brows to the abruptly changing melodies and the volatile back-and-forth between Peterson’s piano and Gillespie’s trumpet. At the end of the songs, their brows would suddenly release, their attention resolving as the music did, and they glanced at each other with a smile.

A few older gentlemen in the room, including Cochran, listened with their eyes closed, as if sleeping to a lullaby. But, under the table, their feet tapped on the ground to the beat of the music, their hands acting as drums on the tops of their thighs. When a song came to a close, they’d all spring awake with life, dazed and laughing like teenagers just off of a roller coaster.

“I learned tonight that I can see people’s reaction to music even behind their face mask,” Cochran said. “And it’s so nice to know that the person across from me is enjoying the same thing I’m enjoying about a piece.”

When asked why the Institute Library thought hosting jazz listening sessions would be valuable, Cochran didn’t miss a beat. “Jazz is like another language,” he said. “For people who aren’t that good at using words to express their thoughts and feelings and ideas, jazz can be a way for people to do that. Well, I guess that’s all art.”

Cochran looked thoughtful for a moment longer.

“And, it’s just a lot of fun.”

Learn more about programming at the Institute Library at its website.