Greater New Haven | Music | Arts & Culture

| Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Minter, who runs the video production company Wheel To Sea with his wife Leah Russell, is the composer and arranger behind Journeys, a series of six new piano books (that shakes out to 97 compositions) for early and intermediate music learners. The project is part of KOA Music, a new Connecticut-based company that Minter plans to expand in the coming year. He chose the name, a type of Hawaiian tree, because of its international flair and ease of pronunciation in any language.

"I didn’t know what the series was going to end up with,” he said in an interview this week at Koffee? On Audubon. “Whether it was going to be easy or difficult for adults or children, for beginners or advanced, and ended up writing all of those.”

But the journey to Journeys began unexpectedly last year, as Minter toyed with the idea of writing a Chinese language textbook. He had the experience: he had been a Chinese teacher for several years in a past life, and had learned what he liked and what he’d change from several lesson plans. But a friend at Yale University Press cautioned him against it—the press’ own Chinese language learning program, Encounters, wasn’t as doing as well as the publisher had hoped. It didn’t seem like the best time to head into that field.

Then a few months later, Minter was talking to his brother, who lives in Mexico with his wife and young daughter. He’d decided to start piano lessons alongside his daughter, and asked Minter what kind of piano music he recommended. Minter racked his brain. It had been 25 years since he’d been a piano student. So he told his brother that he’d look, and report back on what he found.

“And I couldn’t really find anything that cool!” he recalled. “It was exactly the same books I’d grown up with … stuck in the past a little bit. These books came out in the 60s and 70s. They’re good, but there’s nothing kind of out of the box, kind of ‘cool’ about them.”

“And I couldn’t really find anything that cool!” he recalled. “It was exactly the same books I’d grown up with … stuck in the past a little bit. These books came out in the 60s and 70s. They’re good, but there’s nothing kind of out of the box, kind of ‘cool’ about them.”

The wider musical landscape, meanwhile, was cool. Around him, Minter saw music as shifting and dynamic, populated with modern classical composers who were “doing weird musical language” with electronic and jazz rhythms. There were experimental scales and funky time signatures, a nod to world music that inspired Minter to expand his boundaries. Their work just didn’t filter down to early music learners.

“It doesn’t have that diversity and that excitement,” he said of music for early and intermediate learners. “And it’s also sort of based around the European tradition. Which is fine … but hey, there are lots of other traditions around the world that have great music.”

Originally, Minter thought that he’d just write some music for his brother and niece. It was a chance to get back into composition, which he’d loved doing in high school and wanted a reason to revisit. When he wasn’t composing, he scoured sources for music that had been written 100 or more years ago and was now in the public domain (“I just can’t arrange “Despacito,” he laughed). When he hit a roadblock, Russell encouraged him to charge ahead with his writing, and worry about editing after the fact.

As he wrote, aided by a digital keyboard that transcribed directly into his computer, a whole corpus of works emerged. There were syncopated, poppy rhythms, strains of jazz and blues, melodies flecked with world travels on which he’d been, and places he could only wish to go. An Irish folk song sidled up to a Russian one, which joined a Brazilian choro. In add, 97 pieces made it into the final project.

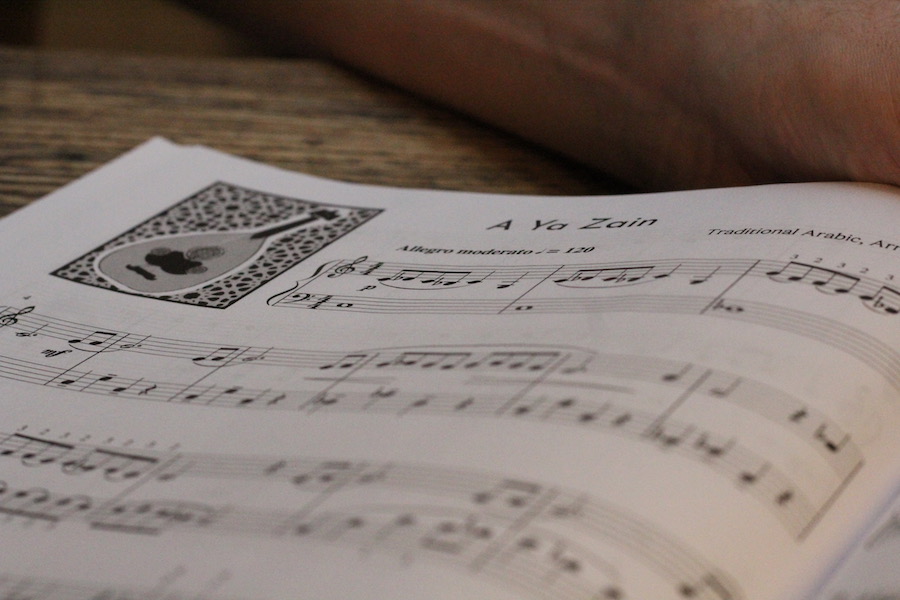

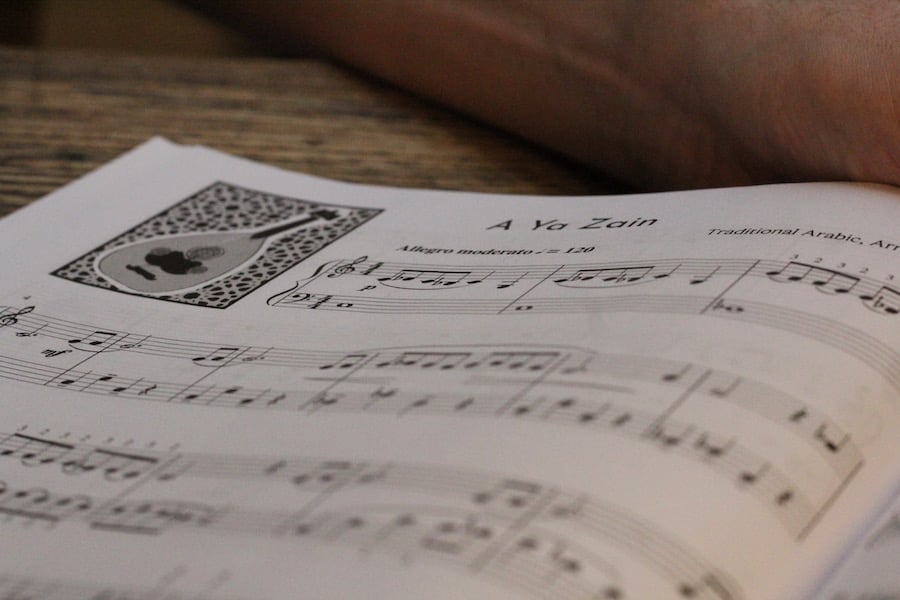

By then, Minter had a sense that the works could go towards something greater. He began compiling the books, with original compositions like “Up In The Andes,” meant to conjure South American melodies, or a new arrangement of the traditional Arabic “A Ya Zain,” with a bouncing, propulsive beat that is ages old.

“I realized that however I wrote the series, I was going to endear myself to some [piano teachers] and alienate others,” he said. “That actually freed me up to just write what worked.”

“I realized that however I wrote the series, I was going to endear myself to some [piano teachers] and alienate others,” he said. “That actually freed me up to just write what worked.”

Earlier this year before publishing, he met with piano teachers across the region for feedback, reaching out to Neighborhood Music School (NMS), Choate Rosemary Hall, and the Hartt School of Music among others. At NMS, he gave a packet of seven songs to Mary Bloom, head of music education. She had an adult student try them out—just two at a time—and returned with high praise for the works: they fell into an ever-elusive category of “serious contemporary work for intermediate levels.”

The student, who Bloom noted for their curiosity, also kept coming back for more.

They’re smart, they’re accessible,” she said. “He has wonderful, colorful harmonies in some of his more calm and flowing pieces. He’s got some really strong rhythmic patterns that are unique and modern. Some authentic jazz harmonies that … they’re a little more current than some of the stuff that you might find out there.”

“The piano repertoire is pretty vast,” she added. “If you know where to look for it, there’s a lot of good stuff out there. But it’s not Will’s stuff.”

Now, Minter is making immediate and long-term plans for KOA Music. After he’s gotten Journeys into circulation, he said that he’s interested in looking towards writing further music textbooks (he mentioned guitar and looping among some of the first), collaborate with fellow composers, do some music writing with area kids, and work with more music nonprofits in the area to reevaluate music repertoire. He’ll be workshopping the book to music teachers across the country, hoping that many will take a chance on the new work.

The core idea, he said, will remain the same—that any music he puts out “should encourage learners.”

“Once they master it, then they’re going to be less afraid of those things,” he said.