| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Let’s start at page one, which is really page eight. We’re in the bathroom with author Leslie Browning, suspended somewhere over her. It’s a small room, quiet except for the sound of her breath. A liminal but lived-in space. Walls, toilet, dusty floor. Blood and fluid gush down her leg. She is terrified; we are terrified for her. There are literal miles to travel before she understands what’s going on.

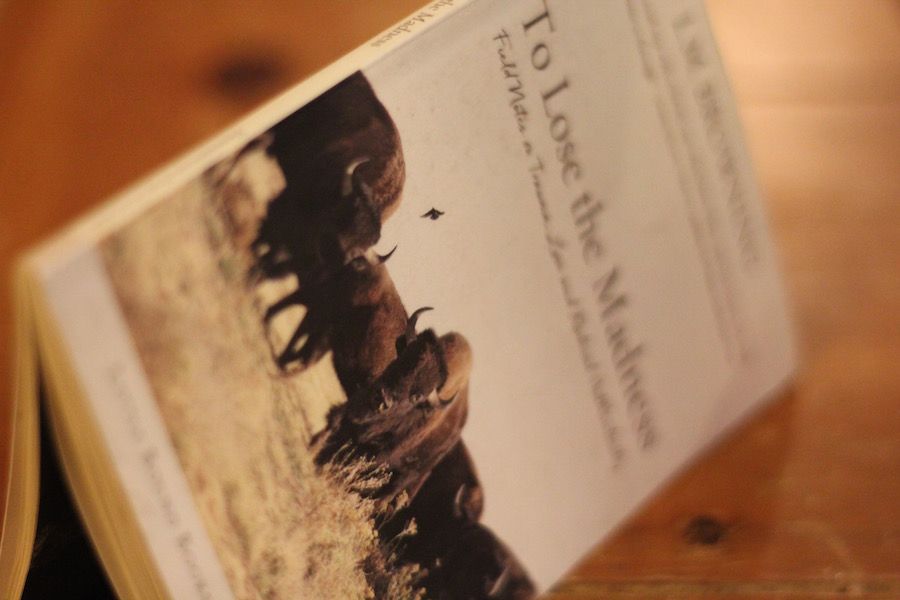

This moment marks the beginning of To Lose the Madness: Field Notes on Trauma, Loss and Radical Authenticity, a bound essay released through Connecticut’s Homebound Publications last year. An intimate and unflinching account of the author’s own grief, the essay follows Browning through the aftermath of a miscarriage with twins, leading the reader through months of botched mental health diagnoses, whole nights spent crying on the floor of an office building, fistfuls of hypotheticals, and the thick webbing of a female friendship that draws her from New England to the American West.

Because the essay is literally propulsive—Browning roams the topography of her mind as she clocks miles from Connecticut to New Mexico with her friend Mallory—To Lose The Madness reads best as a series of tight, relatable and heart-rending vignettes.

In one, she’s learning what it means to navigate the mental health system, where doctors may not trust their patients as much as they should. In another, she confides in her mother that she may never stop counting the ages the twins would be if they’d been born. Another, and Mallory is all but stuffing her her into a car with a fever, and heading West towards a wide horizon.

Homebound, of which Browning is the founder, has turned the essay itself into a work of art, punctuated with photographs of of Colorado and New Mexico taken as the author traveled from this side of the country to the other. Throughout, Browning has left a spray of epigraphs by figures who inspire her, from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Jim Harrison, after whom the essay takes its title.

But despite the essay’s candor—or maybe because of it—Browning didn’t originally intend to publish To Lose The Madness. After her miscarriage, she journaled as a coping mechanism. For months, those writings were primarily “for my own sanity,” she said in an interview last month.

Then while working towards her B.A. at Harvard University’s Extension School, she opted to take a class in creative nonfiction taught by Macy Halford, who had written and edited for the New Yorker’s book review before moving to France in 2012. When she needed material to turn in, Browning realized she didn’t have anything written except her journal entries. So she typed them up, and edited them into “what would become the bones of the essay.”

By the time she finished, she had what she now estimates was 90 percent of the book. Then she learned that she had to present her work to the class. When she did, something she hadn’t expected happened.

“People in the class started coming up to me and saying, ‘you know, my daughter had a miscarriage. She’s in that phase where she can’t talk about it, can I share it with her?’” she recalled. “Or, ‘I almost lost my best friend to suicide, thank you so much for writing about it.’”

“It was the most feedback I’d really ever gotten about one of my pieces,” she continued. “And then it became clear to me that this was joining in to a larger conversation on mental health that was taking place, and that I had to publish it.”

In the months since, she has edited, expanded, and published the essay, given a TEDx Talk at Yale University, done a book tour, and founded the RadicalAuthenticity.Community. Last month, the Arts Paper caught up with her on that larger conversation on mental health.

| The author, photographed at White Sands National Monument. Photo courtesy Leslie Browning. |

The book quite explicitly starts with this miscarriage. But a couple times throughout the book, you make allusions to struggles with mental health that happened before—which I think for women is something that isn’t always talked about.

Yeah. I definitely suffered a few major depressions before that in my life, but nothing to the extent of what happened. That was kind of the precipice event that kind of really unraveled me.

But when you went to the medical establishment, they messed up. And they kept messing up, inflicting greater pain.

I felt betrayed. Like, my trust was betrayed. Anytime we go to any kind of doctor, we are so vulnerable. And you kind of trust that they will be skilled in what they have to do and that they will put your best interests first, and that’s just a huge misconception.

That’s the thing about trauma. The body’s way of dealing with it is certainly not always addressing it. I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about those stages.

Well, I think I had the misconception—which I have since learned was a huge error on my part—that I traveled West, I wrote the book, I am “healed.” I was like: “I am doing great! I’m over it.” I did the TED talk, I released the book, I was moving on, and then I had another breakdown.

And then I felt like I totally had failed. I had to have another set of realizations that healing is a journey, not a destination. I’m never going to reach that destination of “healed.” It’s going to be this perpetual process. And so I kind of came to understand trauma in a whole new light.

There are multiple sections of the book that interested me, and one of them is where you come very clean with the reader and you tell them you had thought about suicide, and you had this realization that suicide does not erase one’s pain, it just transfers it.

In my mindset at the time, which was very dark and distorted by depression, suicide equalled the end of the pain. That was my train of thought. And it was realizing, and even remembering back to when I’ve lost friends to suicide, that it doesn’t end the pain. You are just transferring it. And it is going to be this blast crater affecting everyone who is closest to you.

These are the people that have stood by me, that I care about, that have suffered in their own right, that I would never want to make suffer more, and I realized that I would be giving all of my pain to them. And that was kind of my sobering, grounding moment of—I have this pain, I can address it, I can try to manage it [by] seeking, and not just pass it on to people that I care about and appreciate.

And was it this split second realization or did it take a while? When one is dealing with trauma, you’ve got a lot going on in your head.

Oh, yeah. And you’re not thinking logically and you’re not thinking clearly. It was more—I had the breakdown, and people closest to me realized how close I had come to that moment. And then I saw the reaction. And it started dawning on me slowly that I would have significantly hurt these people. I would have just been giving all of my pain to them. Which kind of—it was that moment of pause.

One thing I was thinking about when I was reading this is this thing where people try to one up or minimize each other's trauma. Did you experience that at all?

Oh, I certainly did. Throughout the process of doing the book tour and doing a lot of interviews about it, there were a lot of people who just did not comprehend what was happening. It was like: “Oh! Why did you feel suicidal?” They just didn’t get it.

Or: “Wow. Why are you still struggling with the miscarriage three years later, four years later? Aren’t you over that yet?”

They said very insensitive things. And it’s like—they don’t grasp it, and aren’t ready to go there due to their own baggage, so to speak. Even dealing with that kind of insensitivity that does surround mental illness and that taboo that surrounds miscarriage.

But it was also hearing other people coming up to me saying: “Oh, I lost my son to suicide.” Or: “I had my own miscarriage.” A lot, a lot of women came up to me and said: “I had my own miscarriage, and I have never stopped counting how old the kids would have been. You mention that in your book and I’ve never heard anybody mention that, thank you.”

So it’s like, there’s this huge group of women who are all silently counting to themselves, and we’re all part of this community, and I didn’t really realize it until I published it and did the tour and met these women.

Well, that’s a whole other part of this. Obstetric and gynecological care in this country is really lacking, even for women who have health benefits and have insurance. I’ve been in the gyno’s office and heard them tell women “well, it’s very common to miscarry one or two times,” and they’ll say it like it’s nothing. I’ve always found that very clinical, but also a little bit unfeeling. And so I’m wondering if that was part of it.

There is a huge insensitivity around it, I think. In the years since, I’ve obviously had to go back to the OBGYN. I’ve had various problems because I have endometriosis, and once I went in because I was having a problem, and they were like “Oh, you’re having a miscarriage.”

And I’m like: “No, I’m not with anybody. That’s impossible.”

And they’re like “No, you are. You’re just lying to us and not telling us that you’ve had a sexual encounter.”

They hadn’t even read my chart. So I ended up going back and forth with them … there was this huge insensitivity around it. And it is a very matter-of-fact thing.

That’s the other half of it. There’s still a taboo around talking about things like endometriosis. And some doctors definitely still think it’s a made up thing, even though it’s well documented!

I actually went to an old-school doctor, an older generation, who thought it was women’s weakness. He literally was like: “It’s all in your head.” And I walked of there feeling so insulted, so dismissed. I almost was like, “I’m not going back to the doctor. Period.”

And obviously, that would have been a huge mistake because it does need to be addressed and treated. But yeah, so many women have experienced that, especially in the 70s and 80s, where there was no real documentation.

You’re very self-aware with your readers—you talk, for instance, about how easy it would have been to become homeless. And then you take readers not only on a mental trip, but also a physical trip. What do you think you learned through this experience, and writing and editing this essay?

I have met a lot of individuals who suffer with mental illness since writing the book. All different diagnoses—everything from schizophrenia to bipolar to depressive to borderline [personality disorder]. And I think the thing that I walk away from is, it’s terrifying. It’s terrifying to not be able to trust your own mind, and it’s terrifying to not know what’s real and what’s just this cognitive distortion due to what’s happening in your brain.

And I think what is worse is that even in this day and age, where we have documentation—you can literally see schizophrenia on an MRI—people still think of it as this personal failing. Like, you can help it. It’s your fault. You’re this weak person, or this horrible person, or this what have you. And it’s just sad. It’s just profoundly sad.

You can’t work full time when you’re going through this—at least not effectively—and you can’t go get social services to help you through it because it’s not like you broke your leg. It’s not like that kind of recognized injury or illness. So it is so easy to go from full-functioning, successful adult to kind of homeless, crippled by this mental illness and not knowing where to turn for help. And it’s just disturbing how easily that can happen. Because there’s this lack of awareness, lack of education, lack of proper facilities and support, and it’s just … it’s this huge hole in the system. One of many, but one more.

I wanted to ask about the role of having strong friends, and the role of this trip. In this beautiful way, your body is a sort of landscape in and of itself, and then you’re physically traveling across the U.S.

Yeah, it was very much the interior landscape and then the actual landscape of the U.S., and it was this dual journey. I was kind of lost in my own wilderness in my mind. People have asked me since going West: “What exactly was it that healed you?” And I’ve had a couple years to think about it now—I’ve never really written about it—but I honestly think it was just so many years of seeing ugly things and having ugly thoughts, and having all of these hard, brutal ugly things happen.

Going out West was a counterbalance to that, where you’re seeing something that’s beautiful, and striking. And awe. It’s kind of like, beauty is what can help ease the trauma that ugliness has caused. And it was just that simple. It certainly didn’t heal everything … but it certainly helped ease everything.

I’m wondering if you can say a bit more about that. You describe yourself as having a heart is made of—what is it?— warm apple cider and flannel.

Yeah. Mallory said that to me once and it stuck. And it’s absolutely true. And so out West, I was kind of this uptight East Coast New Englander out in this laid back, surreal, kind of vision quest Western landscape, and it was kind of comical to begin with. But yet it was exactly what I needed, weirdly enough.

There is all of this mythology tied in with the American West. This expansiveness, the idea of Big Sky Country. Is that what you were experiencing in real time?

Well I do think the East Coast, while I love it—especially New England, I love it—it’s very kind of claustrophobic in the landscape. And when you go out there [out West], you just don’t think the sky will be as wide as it is. And something I mention in the book, it kind of helps your mind breathe, expand, not feel so closed in.

And then it was also after years of thinking “Oh, I’m broken, things aren’t gonna get any better, it’s all the same” and wanting to end it all, it was going out West and seeing that there are all these wonderful things I haven’t seen yet. There is still beauty out there. And that kind of helped me turn the page, so to speak.

You talk in this book a lot about “radical authenticity.” It’s become a kind of buzzword—but there’s really no exact synonym for it. And so, for you, was it still really important to use that terminology?

Well, I kind of used it before I started hearing it as a buzzword. I certainly didn’t coin it—there are many other practitioners who use it and I’m aware of that—but it’s certainly kind of been this buzzword. It was, for me, this radical action of being not only honest with the reader by disclosing all of this, but more so honest with myself after years of saying: “Oh, I’m fine, there’s nothing wrong,” and repressing a lot of my emotions.

Well, let’s talk more about that. One of my favorite phrases is “It’s okay to not be okay.” But I feel like especially as people are curating their personalities on social media, there’s this sense of fighting that constantly.

Well, growing up, I coped by repressing all of the emotions, and saying, “Oh, I’m fine.” I felt like I had to be— for my family, for everything. We went through a lot of hardship. My mom was sick, and we were very impoverished growing up and I felt like I had to be fine. It ... became a way of life that didn’t serve me well as an adult.

After the miscarriage and the subsequent chain of breakdowns, I finally had to start admitting to myself “No, you’re not okay.” And then having lost several friends to suicide, I wished that I had kind of revealed my own struggles, so that they didn’t feel so isolated and alone. So that was my way of transcending all that senseless stuff that happened.

The only way I could do that was sharing my story—which doesn’t give answers, doesn’t tie everything up into a neat little bow, but it’s just stepping forward and going “Look! I’m this high functioning person, semi-successful, and yet I am also a hot mess.”

So it’s okay to not be okay. You know?

Before we finish, I want to talk about this really transcendent moment that you describe in the prologue, with a herd of buffalo.

As I stood there—my creased leather boots breaking through the stiff, frosty grass—I looked dark eye to dark eye—a single female buffalo moved out of the herd and started moving toward me. I was reminded of a painting I saw as a child by Robert Bateman of a buffalo emerging from behind a veil of thick mist. I was transfixed. Here I was broken—a shadow of myself—and she a wild thing, untamed, and strength untold. Some otherworldly grace encircled us. In the space between us, we spoke of the ineffable things—of what it is to sacrifice all of one’s self, of grief, and gratitude—and of the terms every living thing must come to.

I had never seen a buffalo—they’re not here in Connecticut—but it was like, oh my god. We were just driving, and then there was this herd of buffalo with all the kind of archetypes around them. It was just this very surreal moment. And then the fact that one of them came out of the herd and kind of looked at me—you could tell it was a female because of its size—it was this very “everything stopped” kind of moment.

Something about it was just other worldly. I mean, I’m not a person that goes to church. I don’t look for sacredness in human-made objects or ideas. But it was just this kind of natural encounter that felt very transcendent.

And it’s weird, because after I did the TED talk and did the tour, everything kind of hit me again. I had another breakdown. The night I had a breakdown, a wildfire swept through Cimarron, and that whole area was just burned to the ground. That was the same night that I kind of hit bottom again, and it was just this really weird intersection of events. And I think it goes back to, too, that healing is going to be a journey. It’s not a destination.