Screenshot from Zoom.

Is New Haven better off now than it was 50 years ago? Or is the narrative of forward progress an illusion?

Writer, historical researcher, and longtime peace and justice activist Joan Cavanagh raised that question Thursday afternoon in a webinar hosted by the New Haven Free Public Library. “Books Sandwiched: Virtual Author Talks at Noon” was streamed on Zoom and Facebook Live.

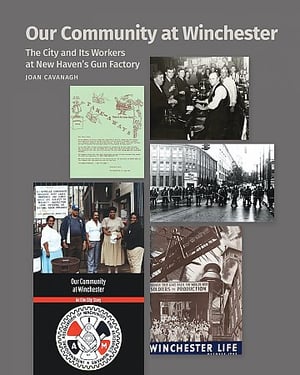

From behind an oval-shaped, archivist-esque pair of black glasses, Cavanagh peered into the computer screen and introduced her recent book, Our Community at Winchester: The City and Its Workers at New Haven’s Gun Factory.

She said that the book, based on an exhibition from the Greater New Haven Labor History Association in 2013, is “only a beginning.” With interviews from 18 former Winchester employees, union leaders, and other individuals associated with the union, Our Community at Winchester traces the workers’ history at the Winchester Repeating Arms Company through the 20th century.

“One of the things I talk about, you have to realize, I felt like this was a whole story in contrasts,” she said. “The whole book is a story in contrasts.”

Winchester created fraught relations between corporate leadership and workers who sought to unionize. In 1955, labor leaders from the International Association of Machinists (Local 609) pushed workers to unionize. In an effort Cavanagh praised as “nothing short of heroic,” the union at Winchester led to stronger contracts and labor strikes in 1969 and again a decade later, from 1979 to 1980. The factory ultimately closed in 2006.

During the hour-long talk, she focused on the contradictions and complexities that continue to color the story of the factory, and she challenged the narrative of forward economic progress that has followed its decline and closure. Topics spanned the pride of neglected factory workers to the current divide between Science Park at Yale and the surrounding Dixwell and Newhallville neighborhoods.

Cavanagh began with the guns themselves, and the people who made them. From the beginning of Winchester Repeating Arms Company, the repeating firearms comprised a majority of the company’s profit. Money from the guns went first into the pockets of the Winchester family, and second into the hands of Winchester’s corporate leaders. The stream of cash then stopped short; the money “was not trickling down to the workers,” said Cavanagh.

And yet, even as they were economically exploited, workers experienced, “tremendous pride in craftsmanship,” she added. Steady labor at the factory also created a pathway to first-time homeownership among Black families, many of whom settled in the city’s Newhallville neighborhood.

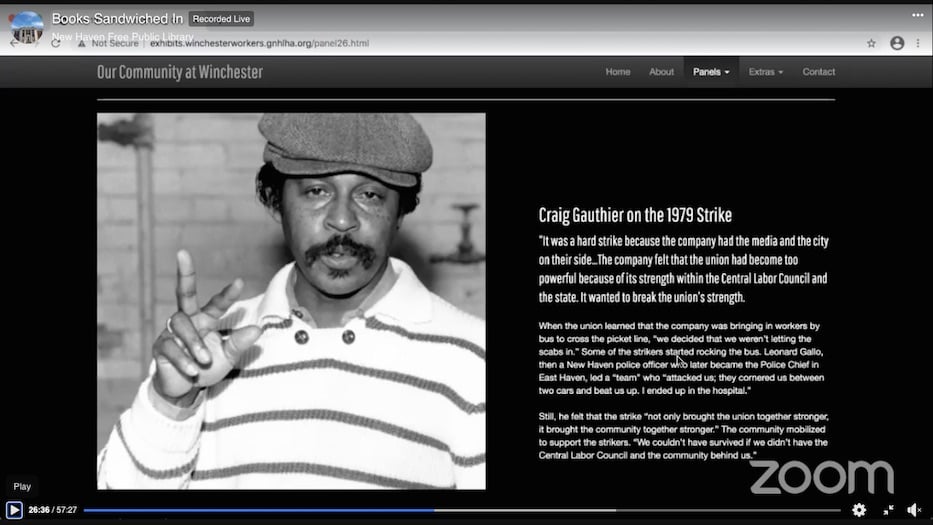

Craig Gauthier, former president of Local 609 and a prominent figure in Winchester’s union history, remembered the plant as the driving force for the community. He lived that history firsthand: after leaving the military in 1966, he moved to New Haven. He began working at Winchester in 1973. Dialing into Thursday’s webinar from his cell phone, Gauthier called the factory “the machine that kept the community thriving,” even though members of the community did not all thrive at the same rate.

Both Cavanagh and Gauthier explored explicit racism at the plant; Cavanagh compared it to a subtler form of economic racism that pervades New Haven today. In the 1970s, the Winchester community was a microcosm of the United States, in unity as in division.

When Gauthier started work at the plant in 1973, Black employees were racially discriminated against by Winchester management and their peers. On Thursday, he described an explicitly racist culture that plagued the Winchester work environment and extended to the union itself.

“There was a lot of internal struggles going on with the union, in terms of African-American people being in certain low-paying jobs,” he recalled. “Some of the fight around the union had to do with the piece work method. And the company felt that a lot of the workers were making too much money…A lot of the workers became so skilled because their pay would be way above average than other workers in the shop.”

“The union understood that this was going to be an ongoing struggle,” he continued. Still, he noted that “Winchester was like a huge family,” and that the union played a key role in its coalescence. That family, which at its height included 20,000 workers in New Haven during the Second World War, ultimately disintegrated and eventually disappeared.

In 2006, U.S. Repeating Arms announced it was closing its New Haven plant. A new entity, the Science Park Development Corporation, then crept in. The Science Park Developing Corporation is a not-for-profit corporation established by Yale, the City of New Haven, Olin Corporation and the State of Connecticut to develop the former Winchester Firearms factory campus in New Haven.

In what Cavanagh considers an extension of “Yale’s land grab in New Haven,” Science Park at Yale is home to start up and established biotech and technology companies, Yale University offices, apartments, and not-for-profit organizations serving New Haven communities. Cavanagh noted that Richard Levin, president emeritus at Yale, called Science Park at Yale, “a renaissance for the people of New Haven.”

“A renaissance? For whom?” she asked in response.

For the surrounding Dixwell and Newhallville neighborhoods, the fortress of Science Park at Yale is no renaissance. A majority of the jobs at Science Park are in the field of biotechnology, and they require a certain level of education. On average, the apartments at Winchester Lofts are priced above $1,500. The barriers to entry are high. As they continue to grow higher, local New Haven residents are being priced out of their communities.

The Winchester Repeating Arms Company, quite unlike Science Park at Yale, provided for the community. The factory brought in jobs and, subsequently, Black homeowners who moved to New Haven and remained in the city for generations. Cavanagh said that Black home ownership is “not being facilitated now, at all.”

While the plant created and promoted an inequitable working environment, she continued, Winchester brought an economic mobility to the local residents of New Haven that has long since vanished. Could it be that the blatant subjugation of workers by Winchester management better served the New Haven community than the insidious network of discrimination modeled now be Science Park at Yale? Perhaps, she suggested.

“This is a picture that’s happening all over the country,” said Cavanagh, as she concluded the Thursday talk. “It’s a very serious problem, and we are all suffering from it.”

To watch the entire talk, click on the video above.