Hamden | New Haven | violence | Westville | Public Health | Rev. Odell Montgomery Cooper | Connecticut Violence Intervention Program

Kirk Wesley, Shaina Smith, Natasha Koonce-Webster, Pastor Gil Davis, Rev. Odell Montgomery Cooper and Melanie Lee. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The stories filled the room one by one, thick and heavy in the air. Two sons, stolen long before their time in two separate acts of gun violence. A young woman killed in her mother’s driveway by a weapon of war. An adult who withstood childhood sexual abuse to protect her siblings. A detective whose quick assumptions about a victim stayed with him—and are now changing policing in Hamden.

All of them were interruptions. All of them led to the same room on Edgewood Avenue, where dozens gathered with the hope of healing. By the end of a single afternoon, all of them had opened the door to new ways to talk about trauma.

Those stories came to Westville last Friday, as Interruptions: Disrupting The Silence author, podcaster, playwright and educator Rev. Odell Montgomery Cooper and members of Connecticut Violence Intervention Program (CT VIP) gathered at BLOOM for “A Healing for Generational Trauma,” a roundtable dedicated to breaking the stigma and silence around violence, grief, and intergenerational trauma.

Top: Attendees gather at BLOOM. Lucy Gellman Photo. Bottom: Participants discuss trauma with dacilitator Natasha Koonce-Webster. Abiba Biao Photo.

For three hours, roughly four dozen participants cycled through the space, learning how to address and survive the “interruptions” in their own lives—and stem the spread of generational trauma that is centuries running. The project is personal to Cooper, who lost her son Jonathan to gun violence in 2016, and suffered a brain aneurysm the following year, on what would have been his 26th birthday.

She has since started what she calls “a movement,” dedicated to addressing and ending intergenerational trauma through a book, play, podcast series and curriculum that all grew out of her experience.

“Today is about you,” she said Friday, standing beside CT VIP Executive Director Leonard Jahad. “We invited you here for you. Recognizing trauma was something that I had to fight through because no one knew how to help me that looked like me. It was untreated. And I suffered.”

"We know that the trauma in our community has been ignored," added Jahad, who knew Jonathan and remembered him as a sweet and talented young adult. He pointed to the difference in resource allocation that he saw after the Sandy Hook massacre, when the nearby town of Newtown was able to bring in grief counselors and child and adult therapists. "A lot of our trauma goes unrecognized and goes untreated.”

Jahad and Cooper. Lucy Gellman Photo.

To heal, he and Cooper said, people have to find a way to talk about the interruptions that they’ve experienced. Before an afternoon of aromatherapy, reiki, nourishing food, and an outdoor fire pit for emotional wellness, the two split attendees into three sections, each led by a trained facilitator. Cooper and Jahad drifted between rooms, listening as groups got started.

At the far end of the shop, attendees crowded in, slipping into their seats as ivy and fabric flowers peeked out from the walls. Across the room, there was a cross-section of Cooper’s own life: bereaved mothers who are part of a group they never asked to join; Hamden Mayor Lauren Garrett, who governs the town where Jonathan was killed; friends and godparents who had loved and still love Jonathan; Det. William Onofrio, who was assigned to Jonathan’s case as a rookie cop.

At the front, facilitator Natasha Koonce-Webster clasped her hands in her lap and looked around the room, making eye contact with every attendee. No sooner had she asked what brought them into the space than a steady stream of interruptions began to flow through it. For many attendees, the specter of gun violence was everywhere.

“An interruption is something that changes what you’re going through,” Koonce-Webster said. “I think that what happens to a lot of us is that you get stuck.”

Top: Facilitator Natasha Koonce-Webster, who described her own interruption as an MS diagnosis after the birth of her third child. Bottom: Patricia Brown-Edwards. Lucy Gellman Photos.

From the middle of the room, Patricia Brown-Edwards recalled losing her two sons, Dennis Carr and Kyle Brown-Edwards, almost two decades apart from each other. In 1997, her 19-year-old son Dennis was gunned down while sitting in a driveway on Congress Avenue, when a bullet intended for someone else ended his life. Seventeen years later in 2014, her son Kyle was killed outside of her mother’s home. Her mother, who is now 93 years old, almost never leaves the house.

In the years since, Brown-Edwards has had multiple heart attacks, including during a meeting of a survivors of homicide support group she attends with Cooper. She’s arrived at the hospital dead on arrival six times, she said. After learning there was no heart disease in her family, Brown-Edwards recalled asking her cardiologist if it was possible to suffer from a broken heart—a phenomenon associated with stress that is in fact documented.

Friday, she said, she had willed herself to come out to BLOOM because the act of grieving—and surviving—is a process with no end point. “I am looking for myself for some kind of peace,” she said. This year, she is struggling with the additional information that the man who murdered Dennis will be getting out of prison this year, earlier than his original sentence. Every time she hears about a legal proceeding, she relives that day.

“I think a lot of people, when they grieve, they think, ‘This is where I should be right now,’” said Koonce-Webster, who described her own interruption as living with Multiple Sclerosis. “A lot of times, we just need to be there for people. People will let you know what they need.”

Pamela Jaynez, whose son was killed in an act of gun violence. Lucy Gellman Photo.

The stories kept coming. Beside Brown-Edwards, Pamela Jaynez remembered losing her son, and then her nephew, to gun violence. She has since become one of the founders of the New Haven Botanical Garden of Healing, which sits not far from BLOOM on Valley Street.

As he listened, Omar Ryan nodded knowingly, quiet as he waited to speak.

Now a violence prevention professional with CT VIP, Ryan “was part of the problem” in the 1990s, he said. After ending up in the state’s carceral system, he dedicated his life to breaking a cycle of violence.

“It’s unrealized trauma,” he said.

“Thank you for being here,” Koonce-Webster said. She looked around to see if people had other interruptions that they wanted to share.

Onofrio, who was the detective assigned to Jonathan’s case, piped up from the side of the room. Six years ago, he was a rookie detective on the force. He saw the file for a 25-year-old Black man, killed close to a restaurant and bar that had a reputation for getting violent. He assumed Jonathan had been drinking.

“I couldn’t be more wrong,” Onofrio said, his voice shaking at points. At the time he was murdered, Jonathan was a budding audio engineer with a job as a barista, working and living in New York City. Onofrio hadn’t seen any of that. When he met Cooper, “I think I failed to pursue the trauma she was going through,” he said. “I was very procedural.”

“I couldn’t be more wrong,” said Det. William Onofrio (top photo). Bottom: the CT VIP table included not only tips around trauma and recovery, but bags of tea for emotional wellness. Lucy Gellman Photos.

He remains grateful for the guidance he got on the job—and the grace that Cooper extended to him. In 2016, Cooper told him “to step back” and rethink everything he thought he understood. When he did, he learned the deeper story of who Jonathan was—a gentle, artistic spirit whose smile lit up a whole room. A young adult who loved his family so much that he’d come back from New York for his cousin’s birthday. He was driving home from that celebration when he was shot and killed at a traffic light in a case of mistaken identity.

“I think learning from each other is one of the best things we can do,” Onofrio said. Six years after Jonathan’s death, his time with Cooper has changed how he thinks about his role. He talks about internal biases, trauma, and hard-to-unlearn assumptions with other cops on the Hamden Police force. He also thinks about internalized and vicarious trauma—and talks about it with fellow officers.

His voice splintering, he said that sometimes he gets home after a day on the job, and wakes his kids up just to let them know he’s there.

“I think we get so used to seeing it on t.v. that sometimes we get desensitized to it,” Koonce-Webster said. “When will we start caring about every child like that’s our child?”

From the center of the room, Darlene Galberth remembered how after the murder of her daughter outside of the family’s home, “no one came to show concern.” She was exhausted and angry, she said. Cooper, who had appeared in the doorway, listened attentively without saying a word.

“How do we address it and take care of ourselves?” she said after a long pause.

Finding The Healing

Melanie Pettigrew-Lee. Abiba Biao Photo.

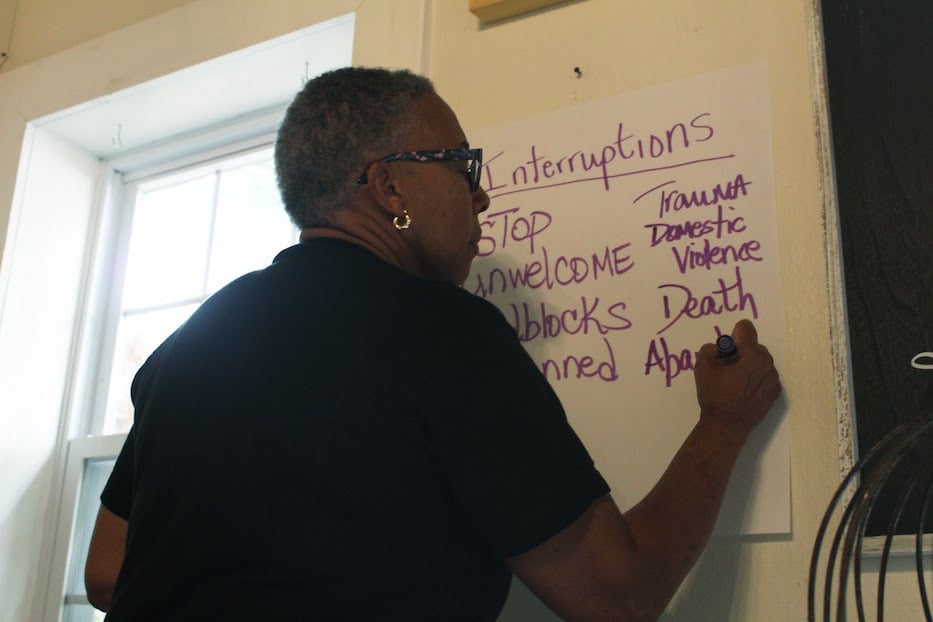

In BLOOM’s “Yellow Room,” facilitator Melanie Pettigrew-Lee ran through a different set of interruptions. With her marker flowing across an oversized pad of paper, she got to work writing down people's responses to their thoughts about the word “interruption'' and the connotation it held.

The words “stop” and “unplanned” bubbled up as Pettigrew-Lee wrote each of them down. As attendees kept talking, some suggested more finite examples such as death and domestic violence.

“When was the last time you felt an interruption that made you feel not normal?” Pettigrew-Lee asked, leaving the floor open.

Martina Campbell immediately chimed in to answer the question, tying her loss of normalcy to when she was sexually abused by her step-father as a child.

“The healing comes from telling a story over and over again, and helping someone else get out of it,” Campbell said. “And because I went through the experience, I can see it in others before they get to where I got.”

She dispelled the notion of healing through forgiveness, saying that other emotions can coexist equally alongside the healing process and serve as a catalyst for change. She acknowledged that for years, she has carried the grief and the trauma so others in her family don’t have to. Friday, she was laying some of that burden down.

“So yeah, I'm angry,” she said. “I've always been angry. But the healing comes from saving someone else. Because I had siblings, too. And I allowed myself to be the victim so they weren't.”

“You know, it's easy for us to say that hurt people hurt other people, but caring people care for other people too,” Pettigrew-Lee responded. “And sometimes we care at the expense of sacrificing not only our sanity, but also our safety.”

"Today is for you," Cooper said. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Teaching people to talk about breaking that cycle is part of the work, she said. Across the space, snippets of conversation floated through the air, each followed by a suggestion on how to speak about them. As she headed towards a CT VIP table outside, facilitator Shaina Smith said that her work is now dedicated to making sure people have the vocabulary to talk about that trauma.

Born and raised in Bloomfield, Smith has lived that herself: she was the victim of sexual assault when she was a child. It was only years later, when she was 19, that she learned the words for what she had experienced. She got to the point where “I know I can function with it,” she said—and she’s trying to pass that message on.

“You know how they say music is the universal language? Unfortunately trauma is too,” she said. “You’re never going to meet somebody that doesn’t have trauma. So that’s what I’m trying to convey to the adults, and to the youth too. They don’t know that they have a voice. That you’re allowed to speak of your trauma.”

Back inside, BLOOM owner Alisha Crutchfield-McLean said she was glad to host the roundtable, and would welcome the Interruptions crew back anytime. She and Cooper met years ago, introduced by a cousin well before the Edgewood Avenue storefront was open. They bonded over not just their hometown—both hail from Boston—but the fact that they’d both experienced death of loved ones as a major interruption in their lives.

“We just instantly connected,” Crutchfield-McLean said. “We’ve been friends since then.”

It was that sense of connection that made her excited to open the space to attendees Friday, Crutchfield-McLean said. When she opened just over a year ago, her vision for the space was driven by a desire to gather community. Now, she’s doing it.

“BLOOM is blooming,” she said. “It takes on a mind and an energy of its own. I just nurture it. I maintain it. I make sure that it’s good to be ready for people every day.”

Learn more about "Interruptions," including how to bring the curriculum to your place of work, here or in the audio above.