Education & Youth | Elm Shakespeare Company | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | Westville | Mauro Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School

Edie Stoehr and Nadia Bellamy. Lucy Gellman.

"I was born free as Caesar!" Sarah Bowles shouted, her knees bouncing, and around her 18 small, neatly clad Romans shouted the line back with fury. She shook out her wrists until her hands looked as though they were made of rubber. "So were you!" she cried.

"So were you!" the Romans bellowed back, extending their arms to point sharply at each other. They already knew what was coming next: We both have fed as well, and we can both/Endure the winter's cold as well as he! Around them, the room seemed to vibrate with each word, its prop-strewn tables and costume racks suddenly more precarious.

They were preparing for their final performance of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, held last Tuesday through Thursday at Mauro-Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School in New Haven's Westville neighborhood. Performed by students in the sixth through eighth grade, the play marked a long-running collaboration between Mauro-Sheridan and Elm Shakespeare Company, whose work with students has become a signature and growing part of its mission.

Sarah Bowles: "It's a debate about what is right."

Bowles, who is the director of education for Elm Shakespeare and abridged the show, praised set designers David Sepulveda and Amie Ziner, directors Justin Pesce and Aleeki Shortridge, and founding program producer Jodi Schneider for helping bring the work to life. As Elm Shakespeare grows its educational footprint, she said, she's often reminded how much of a team effort every production is.

"It's a great play for young people," Bowles said before Thursday's closing, adding that she and the directors were thoughtful about how much violence to cut from the show, how much to leave in, and how to depict it. "What young people really connect to in the play is that one man should not have all the power—that that is not fair. But there's also no one bad guy ... it's a debate about what is right."

Written by William Shakespeare in 1599, Julius Caesar is one of the Bard's celebrated history plays, retelling in verse a story that was, even on the cusp of the 17th century, already ancient history to Shakespeare and his contemporaries. In the play, Julius Caesar (Nadia Bellamy) is returning to Rome as a celebrated military hero, hailed by members of the republic for his leadership. A cloud of adoration follows him through the city, putting his wife Calpurnia (Mama Kamara) increasingly on edge for reasons she can't name.

Sarah Nakhi as Brutus, the original frenemy.

But much like middle school itself, where cliques can only rule the day for so long, not everyone is on board with Caesar's recent star status. Cassius (a wonderfully complex Isabella Capuras) begins to build a group of conspirators, who grow to include Casca (Demealio Black) and later, Caesar's longtime friend and admirer Brutus (Sarah Nakhi). As they fret over Caesar's growing sway and the future of Rome—this republic for which they will later shed blood—their thoughts turn to murder.

In the audience, viewers know what happens next: Caesar is publicly executed by his peers, his friend Mark Antony (Edie Stoehr) bitterly decries his death, setting off a war, bloodshed ensues, and his enemies' fears live on through his son Octavius (Marwa Nakhi), who becomes emperor of Rome.

What has killed him is a fear, repeated over millennia and very present in today’s world, that too much power will corrupt any one person. After all, Caesar is human. Or as Brutus says, "It is the bright day that brings forth the adder, and that craves wary walking."

Semaj Battle-Reed: "I want people to realize, you don't have to kill somebody because they're happy."

At Mauro-Sheridan last Thursday, students sat with the show one last time as they prepared for the final performance, nibbling on pizza and cupcakes before they donned the togas, sashes and laurel wreaths that waited quietly upstairs. Eighth grader Semaj Battle-Reed, who played Metellus Cimber, said that Caesar's plight both made him think more about having stronger, more open lines of communication—and not letting bullies and naysayers get to him.

"This [play] gave me the opportunity to know that this is something I can do," he said, adding that he feels "like Tom Cruise" every time he takes the stage. In Caesar, he sees himself and many of his peers, who get taken advantage of because they have self-confidence, something other people want.

"I want people to realize, you don't have to kill somebody because they're happy," he said. For years, he said, students bullied him because he is gay, making it hard for him to express himself. After coming out this year—and while reading the script for Julius Caesar—he decided that he wasn't going to let anybody take his joy away. When he's onstage, he said, he thinks of his own tormentors. The show makes them feel small.

"Coming in here [to the show] felt very welcoming," he said. "It made me want to express myself even more. That's why we put our passion into this show."

Nearby, students Isabelle Capuras and Edie Stoehr prepared to slip into their roles of Cassius and Mark Antony for the last time. A seventh grader at the school, Isabelle said that she likes playing antagonists, because they draw her out of her shell, and push her to think differently about problem solving. In last year's abridged performance of The Tempest, she played Antonio, Prospero's villainous and scheming brother.

In real life, she said, she's quiet and generally kind to her peers. To play someone so wildly different "makes me feel important," she said. "It helps me shake my nerves."

Edie, who is in the sixth grade, said she tries to think about how the Romans would have acted, and channel that emotion, particularly as she works toward Antony's deep grief and eulogy for his friend. At school and rehearsal, she has started saluting Nadia "every time I see her," in a nod to the role. Theater, meanwhile, has helped her "feel like I'm with my people."

The work has also been a chance for many students to learn about themselves while learning about Caesar’s world. Nadia, a fellow sixth grader at the school, said the role helped her become more confident both on and offstage—and taught her to better communicate with her peers. While Caesar's power originally drew her to the role, she now thinks a lot about how different the play could have been if people had just listened to each other.

"Brutus didn't do that," she said. "He just killed Caesar."

"Yeah," added Na'Riah Chambers, whose character Trebonius is a member of the mob that ultimately kills Caesar, and leaves him lying in a pool of his own blood (depicted with red fabric at Mauro-Sheridan). "I hate that green [eyed] monster."

As students filed upstairs, Pesce and Bowles checked the clock: there was under an hour to go until closing. In a makeshift green room, Pesce gathered the actors in a circle, warming up one last time. When they had shaken out the pre-show jitters, he asked them to lay down on the floor, and close their eyes.

Around the room, the cream and red fabrics of their togas suddenly merged with the dark carpet. The occasional giggle punctured the stillness, a reminder of how very alive these young Romans were.

"We've done everything else," Pesce said. In the room, students' breathing ebbed and flowed as they closed their eyes, and relaxed their shoulders. "Now we're gonna focus on the show. I want you to imagine your character as you breathe in, breathe out."

Around the space, students took a deep breath in, some sucking in air through their noses as others opened and shut their mouths like small fish. "I want you to imagine the first line that you say onstage. And the last line that you say as you leave the stage."

As students came back to the present, Bowles led them in a call-and-response that felt more like an incantation. Who? What? Here?! Us? Together? Ok? It was as if she had cast a spell, and reminded students that they were in it as an ensemble.

The last to leave the room, Sarah Nakhi said she was feeling ready to play Brutus one last time. For her, the play has been a reminder to choose her friends carefully, and be a better one herself. Brutus is kind of the original frenemy—which is not the person she wants to be remembered as when she leaves middle school.

She said that she also thinks about the play in terms of mental health: Brutus is not well before he kills his friend, and starts hiding information from people. It ends in both Caesar's death and the suicide of his wife, Portia.

"Not everyone is a true friend," she said.

On stage, students' deep reading of the script came to life in real time, blending Elizabethian and contemporary references for a Caesar delivered at warp speed. As the curtain opened on Ancient Rome, a wave of handmade signs rose around Caesar, and the city was suddenly somewhere between a Beyoncé concert and a Bernie Sanders Rally. Antony first-bumped him in the streets, and the play rolled forward, suspended between eras.

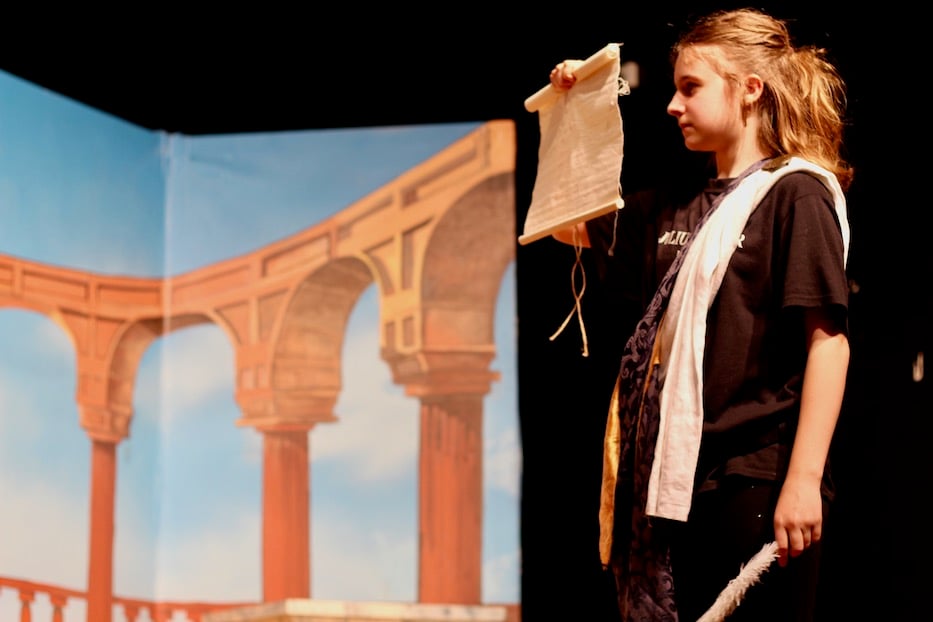

Even in their togas and sashes, students made the language their own, chewing on its weight as they agonized over Caesar's growing power, plotted his murder, dreamed fretful and ghastly dreams, and ultimately lived—and died—with the consequences of their actions. Just as Elm Shakespeare has done in previous productions, students and staff toned down violence, using a bloom of red fabric for Caesar's blood and a glittering, translucent veil to make a spectral vision.

Behind the cast, Sepulveda and Ziner's set transported an audience from New Haven to ancient Rome, with a low-hanging blue sky and honeyed, bright sun that glowed through the arches of a palatial overlook. In the center, the sun sat in the middle of the horizon, such that a viewer could not tell if it was rising or setting.

It felt like a metaphor for the moment's fragility—in the republic of Rome, in a middle school that is still feeling the aftershocks of remote learning, in a city where everyone is navigating a new normal.

With it as their backdrop, students did the rest. Often, they nailed the comedy baked into Shakespeare's work, including his tragedies. Even as he sped through the line "For my part, it was Greek to me," Demealio Black got instant laughs, a flicker of a smile on his face as he exited the stage. When an aggrieved Brutus asked Cassius for his bowl of wine, a few parents in the audience cackled, and at least one responded with an instant "okay!" that garnered a second wave of giggles.

Others mined the breadth of tragedy, which springs from people not talking to each other, and not listening to the women in their lives. When as Calpurnia, Mama Kamara begged Caesar not to travel into town on the ill-fated Ides of March, she sold it with wide, wet eyes and a voice that caught on the line "Do not go forth today! Call it my fear/That keeps you in your house, and not your own."

When she appeared, distraught and scowling at Caesar's untimely death, Edie took on Antony with a rage and depth well beyond her years, as if she was speaking at the funeral of a dearly departed general. Her voice soared and boomed with a certainty that is reserved for eulogies and speeches, issuing a war cry between the lines. It felt far away, and yet eerily familiar.

Even after the lights had come up and parents rushed the stage with flowers and plans for celebratory ice cream, the show's message hung in the air. The Romans had transformed back into middle schoolers. The middle schoolers, in turn, had transformed an audience's understanding of history—and their own.

"Cassius says, 'How many ages hence will this be acted?'" Bowles said. "And it's like, 400 years after Shakespeare, thousands of years after Rome—" she gestured to the empty theater, which would soon be filled with actors. Here they all were.