Black History Month | Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Westville | Literacy | Mauro Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School

.jpeg?width=933&height=622&name=MauroSheridanReading%20-%201%20(1).jpeg)

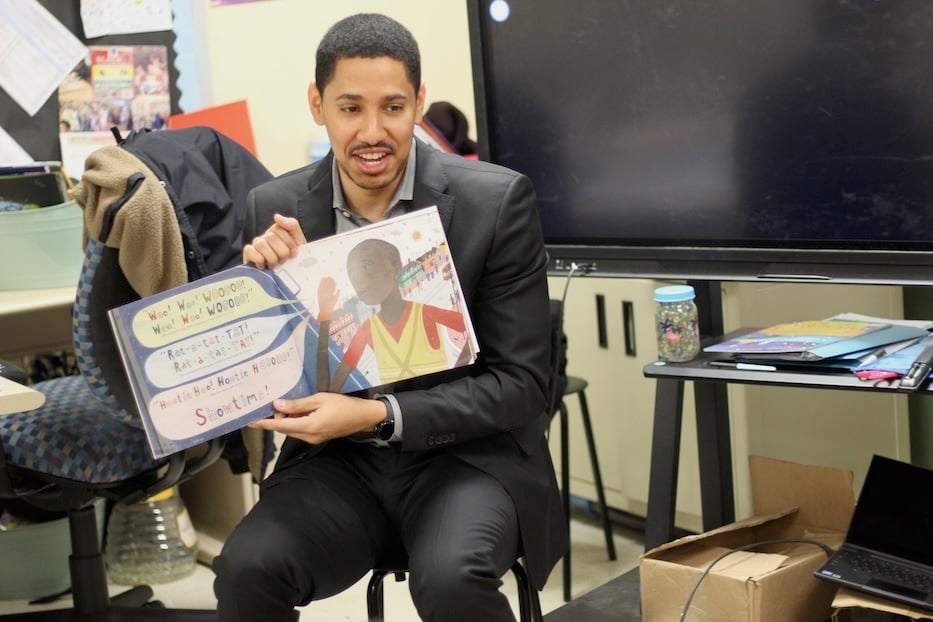

Top: Support staffer Sean Hardy, Director of Professional Learning Edith Johnson, Dean of Students Cedric Robinson and Assistant Principal Kerry Courcey. Bottom: Anthony McDonald reads from Marvelous Cornelius: Hurricane Katrina and the Spirit of New Orleans.

In Mr. G's second-grade classroom, it was 2005 all over again, and the city of New Orleans was starting to flood. On an open page, rain clouds gathered over the Crescent City, gray and menacing. Beneath them, the sky was a sickly yellow; fat drops pelted homes and buildings and began to collect on the ground. By the next page, water rose over roads and houses, taking everything in its path. The protagonist, Cornelius, looked as though he might weep.

From where she sat cross-legged on the floor, Arwa Moutamatai turned from the illustration to her classmate, then back to the book. "No wonder he looks sad," she said.

That scene came to Mauro-Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School on Tuesday morning, as students welcomed community members for a Black History Month read aloud in their classrooms. In two separate rooms across the school, two stories—and their narrators—became windows onto other worlds, teaching the value of empathy and inquisitiveness word by word.

Hardy: "How can you better yourself? How can you help others around you?"

While guest readers visit all year long, Tuesday's included Edith Johnson, director of professional learning and leadership development for the New Haven Public Schools, and Shubert Theatre Executive Director Anthony McDonald. Sean Hardy, a support staffer at the school, has helped organize the visits for 25 years.

"This year, our theme is 'Make Your Mark,'" Hardy said as he waited for McDonald to arrive just before 10 a.m. "It's about being positive, respectful, kind—asking, how can you better yourself? How can you help others around you?"

"The Smartest Class In New Haven"

Just after 9 a.m., Johnson began making that mark before she ever got to Cynthia Puglisi's kindergarten classroom, where students waited eagerly in their pressed red polo shirts and bright, tiny sneakers. The morning already felt bright: it was her eldest son's birthday, and the sky outside was an uninterrupted smear of blue. Standing by the school's entrance, she greeted a few pint-sized latecomers, ready with a gentle hello as they scurried to class.

"This is what I miss," she said. Before her current position, Johnson spent nine years as the principal of Wilbur Cross High School, where she was widely beloved. She transferred to NHPS central office in 2022.

It's one of the reasons she was eager to read, she said. Growing up in Mount Vernon, New York, Johnson—who identifies as Black and Puerto Rican—didn't have a Black teacher until fourth grade, or an Afro-Latino teacher until she got to college. But she did have Ms. Emma Jean Davis, a Black woman and star educator who served as her assistant principal. In Davis, she could see herself—and understood that there was no limit to what she could do.

"Representation matters," she said. "It's important for kids to see people of color in leadership, to know that you can be what you want to be."

At the front of Puglisi's bright classroom, she lived those words in real time. Holding a copy of Ezra Jack Keats' The Snowy Day—the first book by a Black author to win the Caldecott Medal, and the most checked-out book at the New York Public Library—she looked around at the students in front of her, 15 pairs of eyes gleaming back.

After explaining her job—"did you know teachers have teachers?"—she lifted the book for the room to see. On the cover, a little boy stopped on the sidewalk, looking back at his footprints in the fresh, deep snow. A stoplight shone gem-like behind him; a snug, hooded red jacket kept him warm.

"How do I know you have your listening ears on?" Johnson asked the class. When she reads to her sons at home, she explained, she makes sure that everyone is wearing their listening ears. "When you do this—"she tugged her earlobes—"Then I know you're listening."

She took a beat, and asked if students had any ground rules for sharing a book. In the front row, Melanie (Hardy asked that only first names be used) raised her hand. "Be respectful!" she half-sang. She later guessed—correctly—that the story follows a little boy as he plays in the snow.

"Raise your hand when you need to talk!" offered Grace from the back. Johnson beamed. It was time to read.

"If I make a mistake, you'll help me out, right?" she asked. "Cause you know, teachers, we're always learning." As she opened the book, students met Peter, a little boy in New York City who wakes up one morning to find fresh-fallen snow outside his window. Like students might do on a real-life snow day, he suited up and headed outside.

Crunch crunch crunch! Johnson read as Peter's feet touched the snow, and students seemed to lean in a little closer. She followed Peter on his adventures, from whacking snow from a tree (“Have you ever done that?!”) to rolling snowballs for a fight he decided he wasn't old enough to join. Johnson grinned and looked up from the text. On the next page, Peter was making snow angels.

"Can I tell you something?" she said. "Sometimes I throw snowballs at my mommy. Do you know how old she is?" There was a pause. "Guess how old she is. Eighty-one!" Johnson exclaimed.

Johnson promises she'll be back with The Legend of Rock Paper Scissors.

Back in the book, Peter returned home with a snowball in his pocket. The house was warm and dry. Peter's mother listened to him talk about the day and ran a bath. "What do you think is gonna happen?" Johnson asked.

"It's gonna melt!" Melanie cried with a kind of urgency, as if she could reach into the book and keep the snowball cold and frozen. “It’s gonna melt!” Johnson parroted back, and it became a confirmation.

Back in Peter's world—which didn't feel so far away from Mauro-Sheridan's world—the sun was setting on the snow-covered day. When it rose again, he would have another chance to play, this time with the boy from across the hall.

"Maybe we can make up our own ending?" Johnson suggested as she turned to the last page, a tableau of Peter and his neighbor heading back out into the snow. In another universe, Peter went sledding down a big hill, his giggles floating into the air as he sailed down the snow-slicked incline.

When Johnson asked students how many times he'd taken the hill, 15 hands went up all at once, fingers stretching eagerly towards the ceiling.

"100 times!" ventured one student. "1000 billion times!" shouted another named Mark. "109!" kindergartener Natasha chimed in, the rainbow-colored beads in her hair catching in the light.

"I gotta make a phone call," Johnson said before finding a date to return with her favorite book, The Legend of Rock Paper Scissors. "And tell them I found the smartest class in New Haven."

"You All Are Gonna Be Our Future"

Upstairs in Tyler “Mr. G” Genece’s classroom, McDonald kept that momentum going as he slid into a chair, and picked up a copy of Marvelous Cornelius: Hurricane Katrina and the Spirit of New Orleans. Written in 2015—ten years after Katrina left New Orleans reeling—the book tells the story of a sweet-spirited street sweeper named Cornelius, and the way he and his city rallied after the storm.

"No matter what you do, in life, try to always be the best at it," McDonald said, pausing at a dedication page that highlighted Cornelius’ tenacity. "It allows our society, our communities, to run optimally, or really well, because everyone is playing a part. Everyone is trying to be the best version of themselves."

"Right now, your jobs are to be students," he added. "You gotta try to be the best that you can, as a student right now, because you all are gonna be our future. And we need really great kids to grow up to be really great teenagers, to then young adults, to then adults, so that our country, that we all live in here, can be even better in the future when you guys are of our age."

He hadn't even turned to the first page when Sophia Crimley's hand went up.

"Did Martin Luther King write this book?" she asked.

Ariana Heard, one of Mr. G's most curious students.

"No he did not," McDonald said, pointing to the author and illustrator. He turned back to the first page, where a jester's face danced above the first few sentences. In the story, Cornelius was on the job, one hand busy with street sweeping as the other made time to greet the neighbors. At the corner, he welcomed the neighborhood kids, sashaying to the curb when he saw a full garbage can.

"And those spotless streets!" McDonald read from the book. "Oh! How they sparkled!"

"There's a bird!" announced Ariana Heard, crawling closer to the open pages. On the street beside Cornelius, a pigeon looked on questioningly. "A single bird! Just staring at him!"

"Cause he probably wants the food that he's picking up off the ground," McDonald said. As he turned the page, he transformed into a half-singing Cornelius, calling out Woo woo woooooo! Woo woo wooooo! in a voice fit for one of the Shubert's productions. Rat-a-tat-tat! Hoo de hoo! Hoo de hooooo! Show-time!

"That means it's probably time to get to work," McDonald said with an easy, gentle smile. By now, every eye in the room followed Cornelius as he collected garbage bags along the curb and threw them into the truck with aerial force. He became a one-man band, drumming a steady beat as he cleaned the neighborhood.

Mr. G.

"Why they have long hands but we got short hands!" Sophia student cried indignantly.

"Because they're adults and you're still a kid, growing up!" McDonald answered. He held out one arm, letting students size him up for comparison. They seemed, momentarily, satisfied.

McDonald took a breath. Back in the book, a mean-looking storm was moving in. Students wiggled and fidgeted on the rug, some moving to the front of the room to get a closer look. As rain began to fall across the pages, students let out deep sighs and mutters of "oooh."

"That's horrible," one said.

"No, that's not good," McDonald said in agreement, turning his attention to the words on the page. "People and pets, parks and playgrounds, washed away. Schools and shops, streets and street cars washed away. For far too long, water, water, everywhere."

Beside him, Ariana's hand shot up.

"I know what that's called," she said in an almost-whisper. "That's called a flood. I had a flood before. I was sleeping, but I did not hear the water. But my mom took a video."

"Well, good thing you're okay, now," McDonald said. From the page, he pointed out a city in ruin: muck and mud that covered St. Louis Cathedral, streets filled with debris and detritus, a lone Cornelius, ready to weep.

"Why does the earth flood?" she pressed.

"Well, it doesn't always flood," he said "But this city in particular is surrounded by a lot of water. And so sometimes when it rains too much, that body of water ... it has nowhere else to go besides on land. And that's sometimes where you get a flood."

McDonald pressed on. In the book, Cornelius returned to his work. "He can't be stopped from doing his part for his community," McDonald told students as he looked up, and found a handful of hands raised mid-sentence. "He's confidant that, you know what? I can do this."

Around Cornelius, a community jumped into action to help out. The neighborhood barbers and bakers and kids lent their trash-collecting hands. Residents from states across the South, and then the entire country, headed into New Orleans to join in cleanup and rescue efforts.

"Everyone that you saw earlier that was doing their jobs, they all decided that, you know what, if we're going to get our community back together after this big flood, we gotta help out Cornelius," McDonald said. "Everyone came together to help out their community, because it wasn't gonna happen with just one person."

"That's nice," Sophia mused.

McDonald nodded. "When people care about your neighbor, when you care about how your friend is doing, or strangers you don't even know, we can do amazing things when we try to help each other out and have each other's back."

McDonald turned to the last pages, his voice taking on just the edge of a drawl. Eventually, he explained—after the city was clean again, after routine trash pickups had resumed and houses had been rebuilt, beam by beam—Cornelius passed away. His tenacious, vivid spirit was part of the city forever.

"Even though Cornelius eventually passed away, his spirit that he gave that city, that's gonna live on forever," he said, the book still open in his hands on the last page. "Because everybody knew Cornelius, and now the next generation's gonna pass on his spirit."

"He passed away?" asked Ariana.

"Yeah," McDonald said gently while also fielding questions about Seattle, tsunamis, and stepparents. "Once you get really old, that's what's gonna happen to all of us. But in a loooong, long time."

After he had stepped back out of the classroom, McDonald said that he loves attending events like Tuesday's. As a leader in Connecticut's theater scene, he knows firsthand how important—and rare—representation can be. Decades ago, he was one of just a handful of Black kids in a predominately white high school. He never knows who he might influence when he walks into a room.

"I find that it's nice to give back," he said.