Culture & Community | Politics | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Wooster Square

Tony Kosloski's "Equation of Death" at 51 Chestnut St. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A larger-than-life demon towers over the U.S. Capitol Building, its eyes empty and bright white over a huge, bloated mouth with the word CAPITAL inside. One clawed hand reaches for the building’s neoclassical dome, dark nails spreading out toward the ground. The other spreads over a crowd of people who stand outside, their eyes and foreheads identical as they stand shoulder-to-shoulder in a knot of flesh.

The scene is par for the course on Equation of Death, a solo show from Wooster Square artist Tony Kosloski that has been years in the making. Decades after the artist made a public mark on New Haven with a large-scale installation on the New Haven Green, he has returned with an outlook on capitalism, politics, and the current state of global affairs that is as cheeky as it is damning.

For the artist, who has called New Haven home for over 50 years, it’s also right on time.

The exhibition, installed in Melinda Marquez’ intimate dance studio, runs Friday through Sunday at 51 Chestnut St. in Wooster Square. Kosloski and Marquez, who are partners in both life and art, will welcome visitors from 1 to 7 p.m. each day. More information is available here.

The artist inside the exhibition Thursday.

“It’s pretty simple,” he said during a walkthrough of the exhibition Thursday afternoon. “Here’s the equation. Capital controlling government oppresses the people.”

It’s a belief system that he has subscribed to—and created art around—for decades. Born and raised in West Haven, Kosloski started making art during his childhood, curious enough that he pursued it as he got older. After military service in the 1960s, he attended The Cooper Union, living in New York as he studied visual art. It was there that he learned about Taoism and the I Ching, both of which made him think about the role of change in his work.

Outside of class, New York transformed how he saw the world around him. “I got to talk to real artists,” he remembered, including the constructivist sculptor Sylvia Stone and her husband, the painter Al Held. When he graduated in the early 1970s, he moved back to New Haven with the intention of attending the Yale School of Art. Then he realized graduate school wasn’t for him.

“I wasn’t very impressed, so I decided not to be part of that,” he said. Instead, he worked between New York and New Haven, commuting into the city as he lived in a small apartment above Frank Pepe’s Pizzeria. If people knew him at the time, it was from a massive, months-long installation in 1978 called Leftovers on the New Haven Green. In the work, Kosloski rearranged 21 giant timbers 12 different times, stressing the inevitability of change in each shift.

The artist is now working on manipulating a series of photographs of the 1978 installation on the Green.

It was the early 1980s when he heard about the building at 51 Chestnut St. The first time he toured it, there was a metal grinding operation on the first floor, where Marquez’ neat studio now stands with mirrored walls and a flat, spotless black floor. In 1981, Kosloski bought and rehabbed the building, knocking out walls to open up the space.

“It was the only way I could have a place to live and do the work I wanted to do,” he said (four decades later, artists are still talking about the difficulty of finding accessible work-live and studio spaces in the city). Initially, he did sculpture and woodworking in the space, turning it into a dance studio after he and Marquez met in 2004.

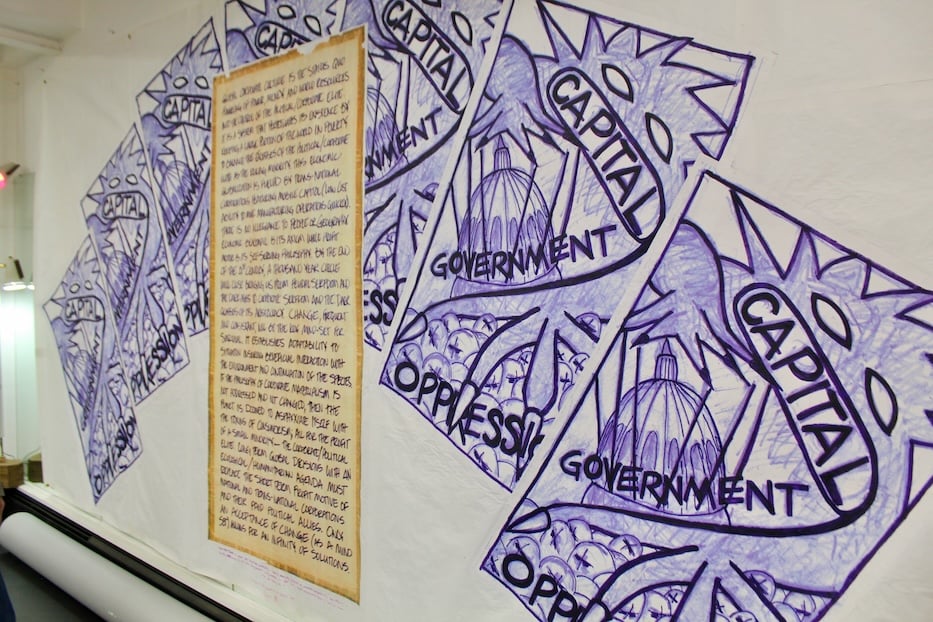

Now, the two have transformed the space into a temporary gallery, where his cynicism around late-stage capitalism looks back in bright, splashy color and large-scale design from every wall. In one piece, for instance, Kosloski has depicted the same scene seven times, the white-and-purple rectangles spread out like playing cards on a losing hand.

The longer a viewer looks, the more they realize that each scene is slightly more off-kilter than the one before, moved just centimeters to the right or left. At the center, the artist has included a panel of dense text taking on global corporate culture. In a sense, he’s making the viewer shift and reset their perspective before they even realize they’re doing it.

Global corporate culture is the status quo funneling of power, money and world resources into the control of the political/corporate elite, begins the center panel. It is a system that perpetuates its existence by keeping a large portion of the world in poverty to balance the excesses of the political/corporate elite as the ruling minority.

“It’s describing the hypocrisy of our culture,” Kosloski said, adding that he traces his anti-capitalist belief system to the end of the Gulf War in early 1991, and first displayed the equation at a show in New York in 1993. “Your only real freedom, as George Carlin said, is 21 flavors of ice cream.”

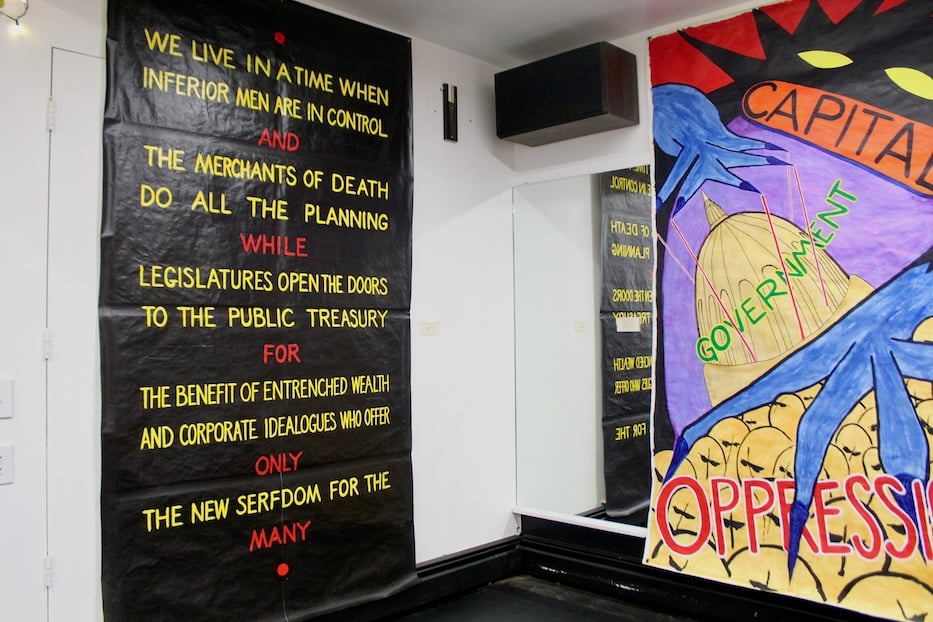

Elsewhere in the gallery, the artist has built on that foundation with massive text panels and illustrations of the same equation, the images throbbing with color. Against the back wall, Kosloski has installed two-thirds of his Equation of Death triptych, using the same reptilian kind of monster to show the harm of capitalism in real time.

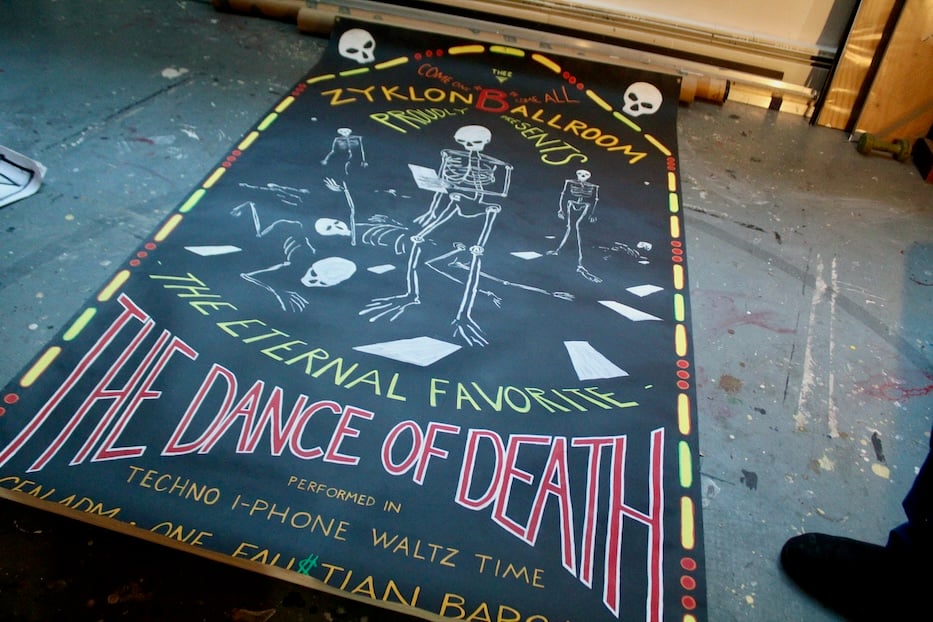

"Equation of Death" and "Wages of Death." The third panel of the triptych, "Dance of Death," is in his studio workspace.

In the first panel, the monster appears against a red sky, its eyes glowing a fluorescent yellow as it reaches menacingly forward with long, blue-black talons. Beneath the Capitol’s dome, turned the color of mined gold, people mill around in a claustrophobic heap, seemingly unable to escape this fate.

In the second, the words More Blood Than Gold drip from the monster’s open mouth as a scale dangles from its claw of a middle finger. An infernal red bubbles beneath it, as if the earth has opened up and magma is spilling out.

In between each, a viewer may catch a glimpse of themselves in the studio’s long, partially covered mirrors, becoming part of the installation whether they intended to or not. It gives them a chance to decide: are they part of the problem, merrily rolling along with the status quo, or are they part of a solution that spreads wealth and focuses on community need?

Other pieces in the show—which is just a small slice of the artist’s work—foreground his interest in the metaphysical realm. In “Cosmic Dancer Out Of Nothingness,” a black-and-red triangle births an explosion of color at its side, in a starburst of blue and orange that spreads to the sides. Around it, bands of gold are cut through with green and black.

A string of twinkling lights extends from one corner. Marquez said that the work, which Kosloski can rotate a full 360 degrees, is often like the extra partner for dancers in the studio, where it is permanently installed.

For an approach that foregrounds the widespread corruption of a political and capitalist system, Kosloski doesn't consider himself an especially pessimistic or cynical person. “I kind of lean into this idea of this all being an illusion,” he said. “It’s this whole Vedic idea that many lives have to be lived, and it’s all a performance. We’ll all be back, one way or another.”

Marquez, who has opened up her space for the show, called the exhibition both exciting and right on time. As it unfolds in the intimate, mirrored room, Equation of Death both marks Kosloski’s first solo exhibition in years and makes a powerful case for anti-capitalism, limited government, and better systems of both accountability and mutual aid.

“I thought it was the right time,” she said. “We are suffering with the Palestinian people. We have given billions of dollars to war, billions to the killing machine. And [in these works] I see this reptile, this monster that is living in this very low place” as a representation of that moment.

“It was important just to put it [the work] up, have people look at it,” Kosloski added. “It’s important for people to make a connection on a visceral level. They look at the art and begin to understand.”