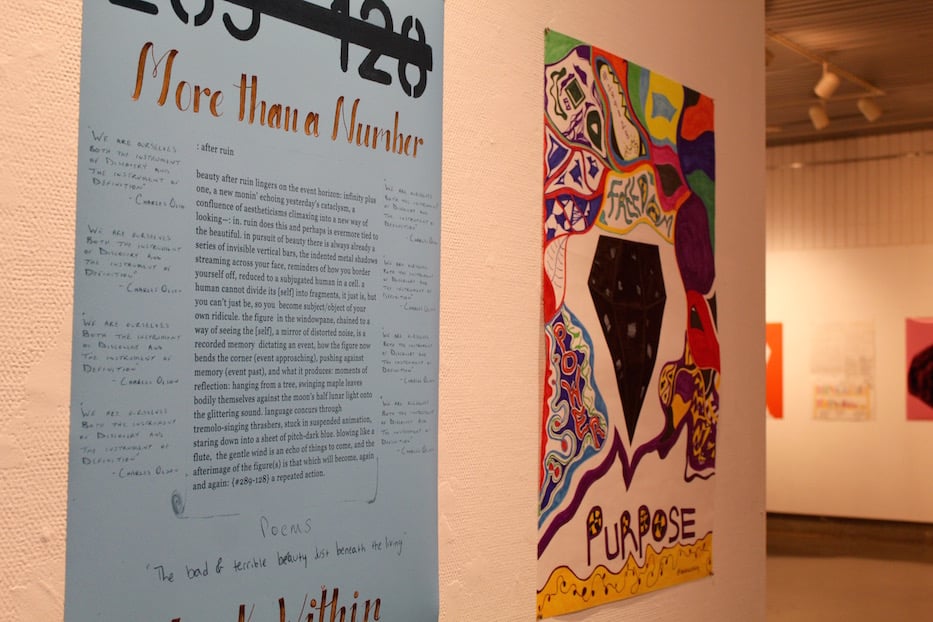

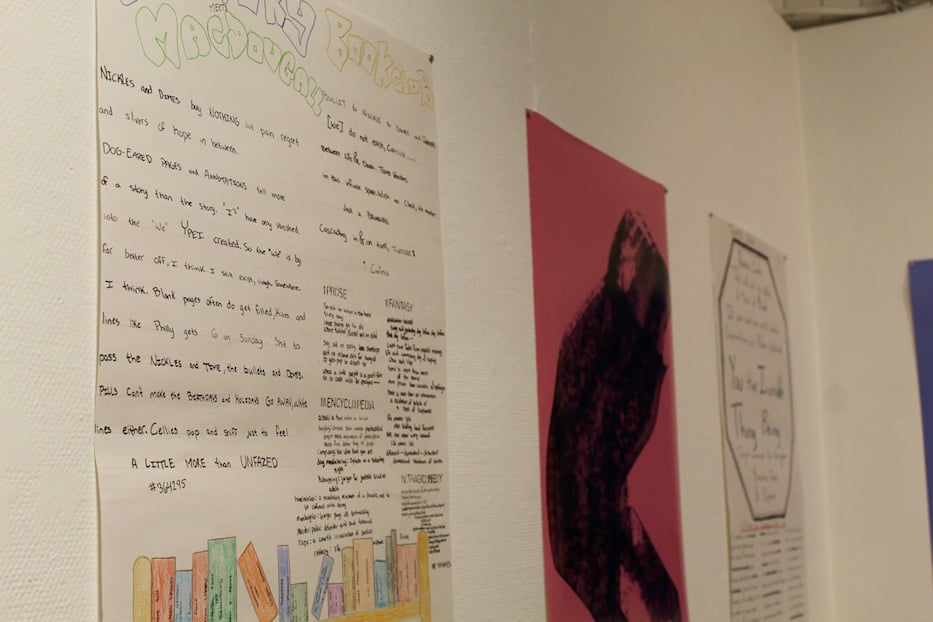

Left: Evan, Introspection, pen, oil, pastels and calligraphy marker. Right: Cal, Black Diamond, marker and calligraphy pen. {#289 128}: More Than A Number runs through Dec. 3 of this year. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The letters float across the page, surrounded by bright, fragmented shapes in every direction. At the center, a black diamond appears, sharp at the edges and covered with small white and silver patches. If a viewer comes closer, the words reveal themselves: Freedom. Power. Purpose. The last dances in yellow and oxblood red across the bottom of the page.

Black Diamond is one of nearly 30 piece in {#289 128}: More Than A Number, an exhibition now running at Seton Gallery at the University of New Haven (UNH) through Dec. 3. Inspired by the poetry of Dr. Randall G. Horton, the show brings together work by UNH undergraduates and students in the Yale Prison Education Initiative (YPEI), which provides undergraduate- and graduate-level classes within Connecticut prisons and correctional facilities.

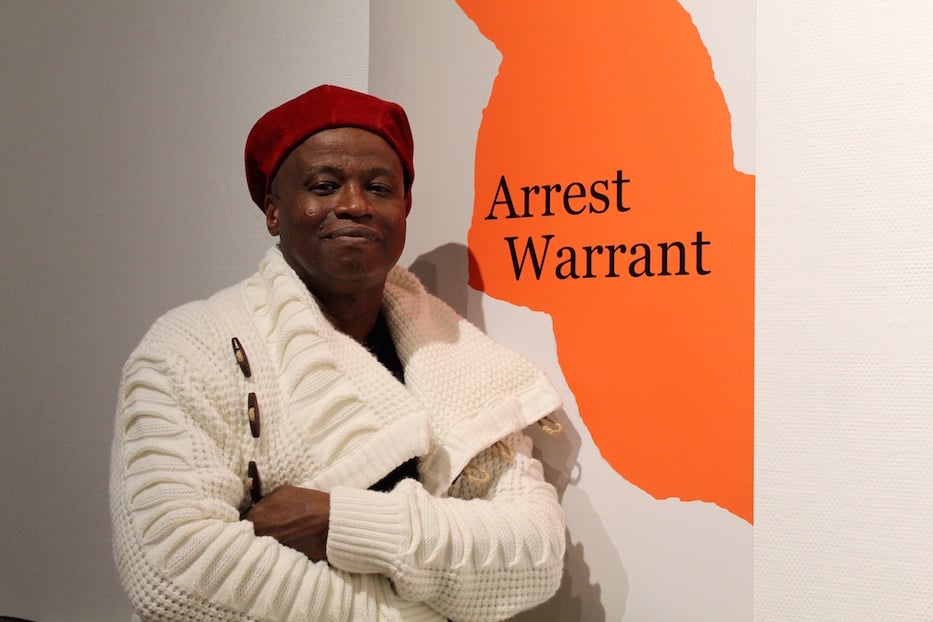

Dr. Randall Gavin Horton, who is a professor of English at the university. "There are many voices and many faces to this thing we call incarceration," he said at the opening Monday.

All of the artists in the show are studying graphic design: one cohort at the university and the other at MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institution in Suffield. Monday evening, the exhibition opened with a musical performance and poetry reading from Horton, who is a professor of English at the university and sits on the YPEI Faculty Oversight Committee.

The exhibition coincides with the publication of Horton's latest collection, {#289-128}: Poems. The book’s title comes from the number that the Maryland Department of Corrections once assigned him as an inmate at the Roxbury Correctional Institution.

“The work comes from a collective voice place within the criminal justice system,” Horton said at the opening, as he signed copies of his book in the gallery. “I hope that in some way, these silent voices that never have a chance to speak are being heard, and I hope that's the influence they're having on the people who come and look. There are many voices and many faces to this thing we call incarceration.”

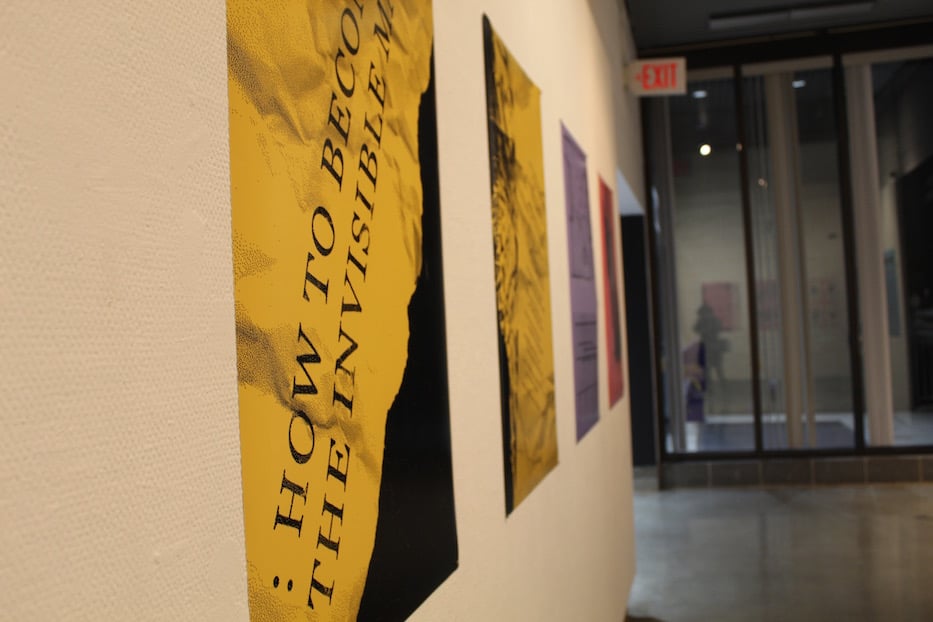

John, How To Become the Invisible Man.

Work on the exhibition started months ago, after Seton Gallery Director Jacquelyn Gleisner connected with YPEI instructors Anezka Minarikova and Bianca Ibarlucea, both graduates of the Yale School of Art who also teach graphic design at UNH. At both the university and MacDougall-Walker, students read Horton’s book of poems, which was released in September 2020. They then designed works in response to the poetry, which weaves a stunning, spareand often gut-wrenching narrative around the inherent injustice of the so-called criminal justice system.

Both groups used the tools at their disposal, which ranged from sleek, digital graphic design programs to poster paper, glue, markers, paint and pens. While Ibarlucea considers herself an abolitionist, “I also believe in creative pathways to education, and widening the design field,” she said Monday. This design project was part of that work. At UNH, graphic design students scanned those poster paper compositions to scale, using digital tools to make sure the resolution remained consistent throughout the show.

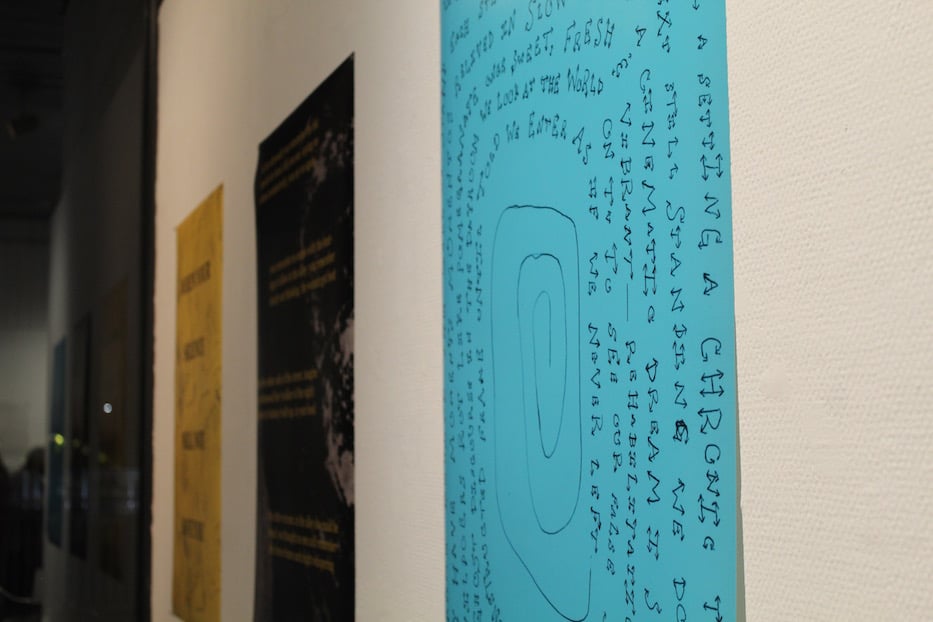

Top: Marcos and Michael's Murdered Self. Bottom: From left to right: Two takes on Your Silence Will Not Save You from Bayley Fair, and Abdullah's Stuck.

It may not come as a surprise that the finished pieces that speak most forcefully to Horton’s work are those that come out of direct and intimate contact with the prison industrial complex. In Abdullah’s Stuck, for instance, a viewer is pulled right into a labyrinthine pen on paper composition, set on a poster so neon blue it nearly glows.

The words to Horton’s poem Rhetorical, Perhaps are barbed at the edges as they wrap around a spiral at the center of the page, becoming art objects even as they tell a story of claustrophobia and repetition within the carceral system. His final words in the piece—"we enter as if we have never left”—come to life in an entirely new way.

So too in Khari’s marker-on-paper Abracadabra, one of three student prints inspired by the same poem. In the poster, two thick, fleshy red hands grasp the bars of a prison cell, bending them outward. Behind them, on a tiled yellow wall, a red heart blooms where a body should be. The words of Horton’s eponymous poem—“long before you knew/something changed inside//you became icicle cold/as if what lay before us”—appear in neat, tiny black text along the length of the bars.

Khari’s marker-on-paper Abracadabra.

Beside it, two of UNH senior Bayley Fair’s interpretations on the same poem look out at the viewer in black and yellow, the letters neat and glistening. On one, what looks like crumpled paper appears behind the words “the lump in your throat/before you left, you forecasted//each lie we would eventually speak/when you said i’m out.”

There is lively, often compelling cross-talk between pieces, which play with line break, spacing, and illustration as they reinterpret and repackage the book’s contents. Horton’s words vibrate and thrum through pairings such as Joy & Pain in Residence, Smudge I and Murdered Self, placed side by side at the back of the gallery. In Smudge I, an inkjet print with no artist’s name attached to it, a thick, smoke-like smudge of black charcoal winds down and across a pink page, giving it the appearance of a rubbing. Beside it Murdered Self shows inmate number 356-057 painted in black against red construction paper.

Horton’s words ring out in thick painted letters across its surface: “in another life your murdered self/be more alive than dead.” The title of the artwork is taken from the fourth section of his poem Ars Poetica (3): Stay Woke. The delicate, almost calligraphic quality of the paint stands a jarring contrast to words, all set against a backdrop that sets off alarm bells with uninterrupted blocks of red.

Kyle, Book Clubs Collide. The works beside it are Smudge 2 and Traffic Stop, a marker-on-paper composition from YPEI student Andrew.

There is also cross-talk between the book and the artists, making clear the layered, collective stories that Horton’s collection holds. In Kyle’s colored pencil on paper Book Clubs Collide, the artist has put his own spin on Horton’s multi-part poem Roxbury Correctional Book Club. At its base, Kyle’s composition is decorated with a sort of abolitionist bookshelf, from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow to Jayson Reynolds’ Long Way Down.

{#289 128}: More Than A Number feels intimate, curated in a way that is intended to give each work—and each artist—the same space and dignity that Horton’s text commands. There’s a clean and gridded format, allowing the words to fill the space in between. And they do, moving from the dayroom, book club and claustrophobic hallways of the Roxbury Correctional Institution to a Brooklyn of the 1980s and 90s that no longer exists.

They give Horton’s poetry a new dimension, ensuring that works like A Primer for Surviving a Traffic Stop never get easier to read. Fair, who was one of several UNH students to work on the exhibition, said that her involvement made her think more critically about the prison industrial complex in the U.S. Beyond watching television shows that included or took place inside of prisons, she said she'd never spent time thinking about the possibilities of reform and abolition.

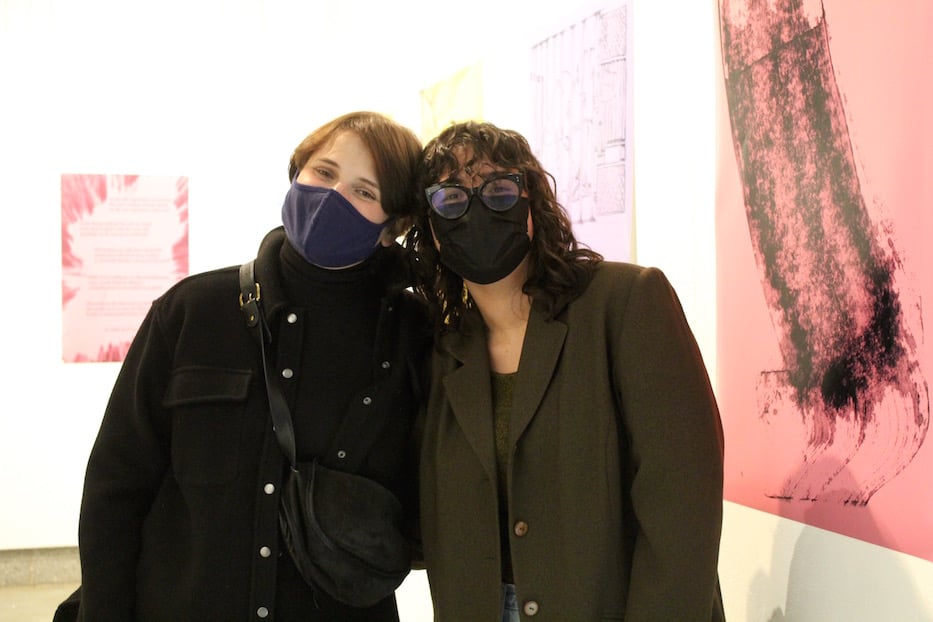

YPEI instructors Anezka Minarikova and Bianca Ibarlucea.

“I don’t think I’d ever sat down and thought ‘Why does it have to be this way?’” she said at the opening Monday night.

Horton, who now thinks of himself as an abolitionist, called the show a moving representation of his work. In the book, a collection of verse and prose poetry that deserves multiple close readings, he shape-shifts between different experiences with the carceral state, using the economy of language as his most powerful device.

He was quick to say that he stands on the shoulders of many who have come before him, including poets Etheridge Knight, Gwendolyn Brooks, Robert Hayden, Lucille Clifton, Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez, as well as Until We Reckon author Danielle Sered. Two decades after surviving prison himself, he is part of PEN America’s Prison Writing Program and the Civil Rights Corps in Washington.

“It feels pretty good to see your words interpreted in these different ways, and see how the students came up with these images,” he said. “It's humbling, as a matter of fact. It's like the art has found another way to recreate itself and to live.”

"People are sort of programmed into this punitive punishment type thing," he added of the current carceral system. "How do you do a more holistic type of approach, where everybody's involved and working toward a solution?"

{#289 128}: More Than A Number runs at Seton Gallery through Dec. 3. Seton Gallery is located at the University of New Haven, 300 Boston Post Road, West Haven Conn. For hours and more information, visit its website. All visitors are required to wear masks in the gallery and show proof of vaccination or a negative COVID test.