Kari Coyle, Harry Coyle, and Jackie Gaudioso-Levita. Lucy Gellman Photos.

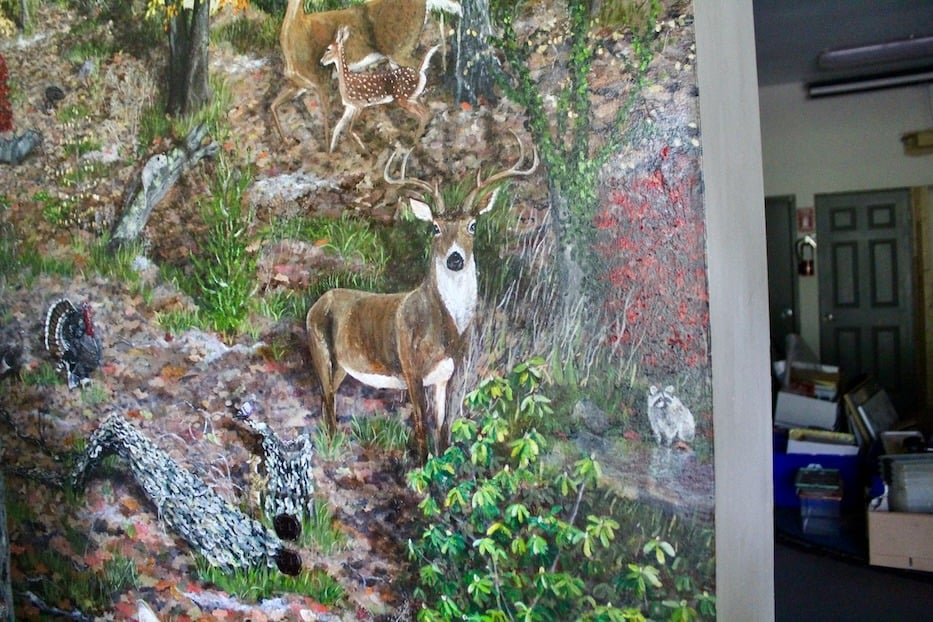

Kari Coyle stood in the doorway of the Edgewood Park Ranger's Station, surrounded by at least two dozen of her favorite woodland creatures. An owl circled, eyeing a chipmunk that would become its lunch. A dawn-colored Marsh Sparrow soared towards the water, ready to make its home. A deer and her spotted fawn trotted cautiously by. In the foreground, a lazy-eyed coyote stared right out of the frame, its jaw hanging open in a sort of a lopsided smile.

Around her, the seasons changed, and then changed again. The sun set on spare autumn trees, their leaves ablaze, and then rose back into the sky, glinting on the water below.

Coyle is the creative brain behind a new mural inside the Edgewood Park Ranger Station, still closed to the public as it waits for much-needed city repairs. The outgrowth of a passion project, the work shows the park in all four seasons, with animals and plants that are specific to each. In the process, it becomes a vibrant game of hide-and-seek, bringing attention to some of the man-made problems putting the park and its inhabitants in danger.

"It's not just the animals, it's the stories," said Coyle, the graduate registrar in the History of Art Department at Yale. "These are the animals that are here. We need to be careful, be mindful of them."

Coyle started the project earlier this year, after thinking about how badly the ranger station needed a facelift. For her, the space is a second home: she's both an ardent lover of parks and the wife of longtime Park Ranger Harry Coyle, who has gotten to know Edgewood Park over decades of service. Her son, Henry Edward Coyle, grew up doing service projects in Edgewood and the West River. For years, she’s worked as a seasonal parks employee, doing everything from nature education to wreath and candle making at the holidays.

So when she noticed that the bathrooms were "a jaundiced yellow" that looked like they had seen better days, she came in to paint them. After tackling those walls, she turned her attention to the main entrance, just beyond the station's huge double doors.

A mural, she realized, could be both a teaching device and a love letter to the park. She mapped out a design that would span all four seasons, with vignettes dedicated to the animal life cycle and very real risks of climate change and destruction of habitat. She met with Dennis Reardon, president of the Menunkatuck Audubon Society, and artist Tony Falcone, whose work on murals and large-scale art pieces spans over four decades in New Haven.

And then, every weekend she could, she began to paint. Besides park-goers, who stopped by on their daily jaunts and dog walks through the park, her most dependable company was Douglas, a Cherry-headed red-foot tortoise who is over half a century old and lives in the station’s reptile room.

That it felt natural, perhaps, isn't a surprise. Coyle, whose animal portraits have helped people honor and memorialize their pets for years, has been using art as a form of catharsis and communication for her whole life. As a kid, she turned to artmaking early, using it to get past a learning disability in English. Inspired by her mother, a visual artist, and her grandmother, a ceramicist, she illustrated stories, so taken with the craft that she considered arts education before ultimately becoming a registrar.

For years, she said, she’s played with the idea of a large-scale work. This became that canvas. "Dreams do come true," she said.

Top: Douglas, the Ranger Station OG. Bottom: A detail of the mural.

The result is both a zoologically fastidious teaching tool and a reflection of her love for a place that nurtures so many New Haveners. On the left side of the work, spring and summer come alive, with a tree that sprouts brilliantly into bloom and a blue lake stretching out in the background. In the lower register, wildflowers fill the space, the grass beneath them lush and emerald green. A groundhog emerges from his hole, skeptical but ready; an Eastern Bluebird spreads its wings wide. Across the wall, fall and winter sweep over the park, transforming it as deer, squirrels, wild turkey and a falcon energy from the paint.

The level of detail is delicious: A pair of foxes play, their wide jaws flung open in delight. A skunk sprays a coyote, causing its eye to seem temporarily lazy, as if something is askew. An owl swoops in for its prey. From the tree, two raccoons peer out at the viewer, as if they are sizing them up. Coyle explained that they are close to the water because the animals, much like humans, wash their food.

Every inch is a learning opportunity, a reminder of how to care for and nurture the natural habitat of these furry and feathered friends. Of the three different bat species in the park, for instance, Edgewood's brown bat population has been devastated by white-nose syndrome, a deadly fungal infection that was introduced to North America through trans-Atlantic air and shipping trade in 2006. Or take the humble Marsh Sparrow, whose homes are disappearing at an alarming rate due to sea level rise. Or the difference between cattails and phragmites, the latter of which are invasive and signal a decrease in area bird populations.

"This gives the rangers a way to talk about climate change" and some of the dramatic shifts that have happened to the park over the last several years, she said. As if on cue, Harry Coyle jumped into the conversation, noting that the park's Canada Geese no longer fly South, because it's warm enough for them to find food during the winter months. That might sound fine—but geese can displace other birds, particularly those that rely on marshy conditions for their nests.

In the next months, Coyle hopes to add a detailed key with close-up photographs of the mural and explanations of the animals pictured, including how several of them interact with and rely on each other for the natural life cycle.

But already, a viewer can find plenty of her personal flourishes: there's a portrait of ranger station resident Myrtle the Turtle among the high grasses, a nod to Beatrix Potter in a hare that perks eagerly up, peering from behind a knotted tree trunk, a depiction of her two-year-old Beagle Max, who reminded her of the people who stopped by with their dogs. In the grass by the floor, she has incorporated a button, a nod to her maiden name that seems entirely plausible.

"The animals are not just here for display," she said. Rather, each contains an educational opportunity.

On a recent Wednesday, Coyle opened the station's front doors and bounded toward the mural, buzzing between animals as she pointed out winged, warbling, half-burrowed and grounded creatures who together make the park what it is. As she looked on, Outdoor Adventure Coordinator Jackie Gaudioso-Levita noted how much it reminded her of the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center in Hawaii, where a mural by the artist Kathleen Kam shows the damage that non-native species have done to the island's natural habitat.

As he checked in on the animals that call the station home—several snakes and turtles that live in half-lit, warm tanks behind that front wall—Harry Coyle added that he hopes the mural is the first of many environmentally-themed artworks to grace the center. "It's not just a park building," he said, lifting up a West African Egg Eating Snake named Queen Amina (she was named by Gwendolyn Busch Williams, head of the city's Youth & Recreation Department). "It's more than that."

Outside, Edgewood neighbor Justin Hawkins caught a glimpse of the bright color, and came by to take a closer look. As a resident of the neighborhood, he runs in the park almost every day, often passing the closed ranger station. Wednesday, the crisp fall weather found him on a walk with his 16-month-old daughter, Julian. Lifting her onto his shoulders, he pointed out several birds, cooing after a requisite "what do the birds say?"

"It looks beautiful!" he said when asked about the mural. "We try to teach her most of these animals from the books in our living room, then we point them out when we see them."

That's the goal: to both delight park-goers and to teach them about a precious and imperiled natural resource. Coyle, meanwhile, hopes that it’s a starting place. "I would love to do more!" she said.