Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | The Arts Council of Greater New Haven

Alisa Bowens-Mercado Photo.

Manny Rivera was always cooking up something. Sometimes it was a fragrant sancocho that took five hours from start to finish. Sometimes it was a cultural festival that brought neighborhoods together to dance. Or a 3 a.m. picnic on the New Haven Green, with a handful of best friends in tow. Always, it left everyone with full bellies, and fuller hearts.

When he died suddenly at the age of 52 last month, it left a community reeling. He was buried at Evergreen Cemetery last week; the family still does not have a cause of death. His sister Carrie Cobián said that he was healthy and energetic in the days leading up to his death on Feb. 26.

Friends and family remembered Rivera last week, in a series of interviews that told the story of how deeply one person can touch hundreds of lives in a small city. He is survived by his mother Nilda Cobián, for whom he was the primary caregiver, as well as his sisters Carrie and Adelisa Cobián, Monique and Laura Rivera, his brother Jonathan Rivera, and a bevy of nieces and nephews who adored him from Puerto Rico to New Haven’s Kimberly Avenue.

From the time he was young, Rivera held fast to New Haven’s cultural community, which he treated as a canvas capable of diverse and joyful expression. The long list of local nonprofits he worked for over the course of his career—including the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, AIDS Project New Haven, and Liberty Community Services—became one testament to his unflagging energy. The indelible impressions he left with friends was another entirely.

“The thing that strikes me so is just how committed he was to the arts, to the community, to forging a way forward,” said Rivera’s longtime friend Jonathan Berryman, a music educator and founder and director of the New Haven Heritage Chorale. “If you never argued with Manny, then you never knew Manny. He would insist that you make your thinking visible. From how to best approach things, to what the best answer was for the artistic world.”

Rivera entered the world in May 1968 in New York City, bubbly and opinionated from the time he could speak (“he was true to that Taurus life,” remembered Berryman). Born to Nilda Cobián and John Frank Rivera, he moved to New Haven as a kid and remained in the city for over four decades.

Just some of the lives Rivera touched. Top row: Jonathan Berryman, Aleta Staton (pictured with Toto Kisaku and Elizabeth Nearing), Alisa Bowens-Mercado. Center row: Sean W. Hardy, Rivera himself, and Debbie Hesse. Bottom row: Babz Rawls-Ivy, Ryan Sperry and Ricky Mestre, and Hardy and Rivera before the pandemic. Lucy Gellman, New Haven Independent, and contributed photos.

He had dozens of titles, but brother, son, and uncle Manny may have been the ones he wore most proudly. Growing up in the Hill neighborhood, he became a role model to both fellow students at school and to his younger siblings at home. Years later, he brought that same approach to caring for his nephew Nelson, with whom he was especially close. This summer, Rivera was planning to take him on a series of college tours in the tristate area.

“He took the role of a dad,” recalled his younger sister, Carrie Cobián, in a phone call Friday morning. “He was always very attentive to my needs, and then later to the needs of my kids. He was such a good role model. He would say, ‘we’re the village.’”

Cobián described him as deeply proud of his Puerto Rican heritage, which was often the first point of order after a brief introduction. While she was “the shy one,” her big brother Manny always knew what to say, she said. Whether he was going to the classroom or the board room, a discussion on cultural and economic equity always came with him.

By the time Rivera graduated from Richard C. Lee High School in the 1980s, he had gained a reputation among his friends as a community connector. It was one he had just started to grow.

In the early 1990s, Rivera started doing outreach for AIDS Project New Haven, now called A Place To Nourish Your Health (APNH). The city was at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and Rivera concentrated his efforts on raising awareness in Black and Latinx neighborhoods. As director of volunteer services at the time, Inner-City News Editor Babz Rawls-Ivy remembered him as eager to help, with an easygoing attitude and starburst of a smile that made him a fast friend.

“He was such a good guy,” she said. “He was the kind of guy where if he went somewhere with you, he would have your back. He looked out for you.”

He was also fun, she said. When she left APNH in 1995, she stayed in touch with him. Every few months, she’d run into him at a cultural event or outdoor concert, which he often upgraded to a dance party with his presence alone. When she moved from Beaver Hills into a new home in Newhallville, he brought wine by her porch to christen the new space. She saw him for the last time a year ago, while passing through City Hall. The two talked about a trip to Florida that he was hoping to take. Then the pandemic hit.

“He was the party,” she said. “His death was a huge shock to my system. It was a huge shock. He was always full of life. It just seemed so strange.”

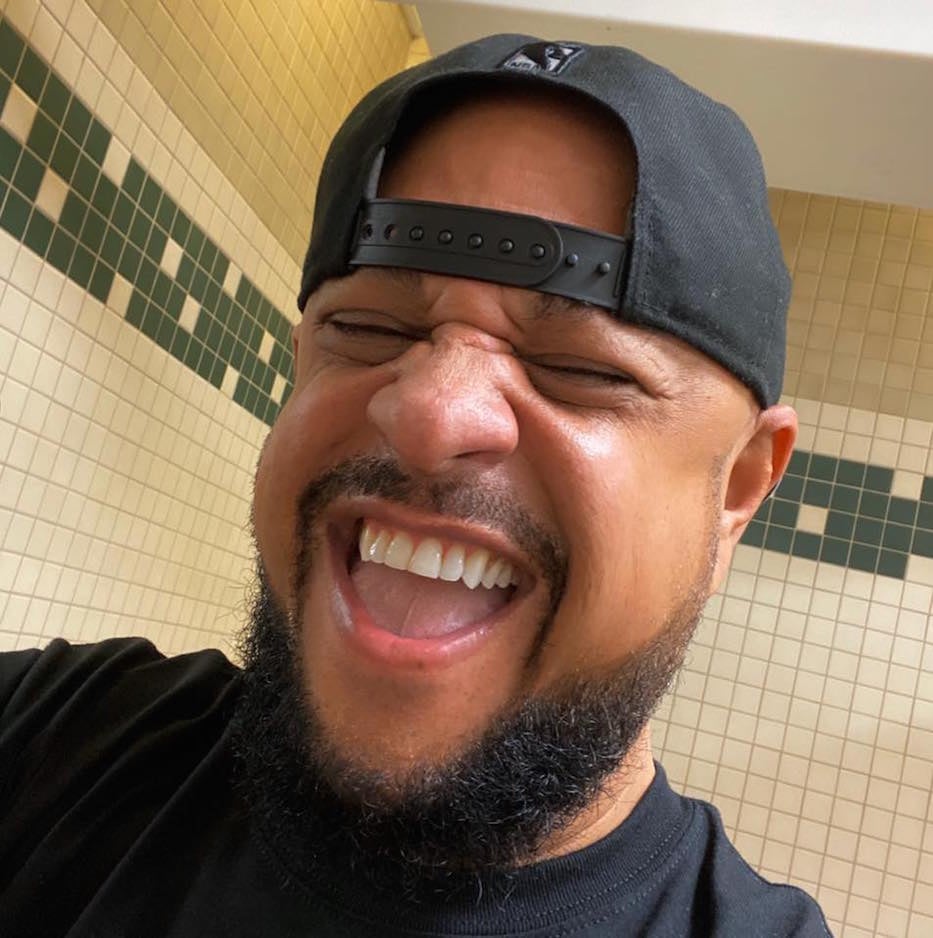

Rivera. Contributed Photo.

Rivera had that magnetic effect everywhere he went. In the late 1990s, local journalist Michelle Turner met him when she landed an assignment covering Latino Youth Development, Inc., of which he was then the director. At the time, the organization ran a summer program for dozens of young people in the city. Turner took to Rivera for his no-nonsense manner from the moment they met. They stayed in touch for the next two decades.

“He made sure that people of color were represented in rooms that didn’t have representation,” she said. “He would definitely let you know how he was feeling about something … definitely no holds barred. When I would run into him, he would give me tidbits about what was going on in communities. He was always good for that. Very active in the community.”

Rivera also made a first impression because he was sharp, she said—sharp-tongued, sharp-witted, and always sharply dressed. He was a man who took pleasure in his outfits, and also in his company. If he had time for a friend—and he always did, no matter how busy he was—he made them feel listened to and seen, she said. When she was getting ready for his funeral at Evergreen Cemetery last week, she heard his voice in her head.

“All I could hear was Manny saying ‘Girl, I know you are not coming in here without no makeup!” she remembered, laughing. “And so I made my face.”

“We had a lot of conversations about race,” she continued. “And a lot of conversations, different solutions, about what could be done and how to do it. We both had concerns about kids … about what was available to them. And how you build community between Black and Latino people, and how to make it better for us. I’m gonna miss those. I’m gonna miss Manny on so many levels.”

In the early 2000s, Rivera started taking courses at Gateway Community College that bloomed into undergraduate and then graduate studies at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU). While he studied political science and public administration, it was arts and culture that kept pulling him back. During his time in school, Rivera worked as the director of community cultural development at the Arts Council of Greater New Haven.

Debbie Hesse, the Arts Council’s director of programs and artistic services at the time, remembered him as “able to tap into the soul of New Haven.” It was Rivera who thought to go into neighborhoods and partner with organizations including JUNTA, the New Haven Board of Education, Regional Water Authority, the New Haven Free Public Library, the Greater New Haven NAACP and all of New Haven’s six colleges.

In fall 2003, he coordinated “Nuestra Herencia” ("Our Heritage"), a celebration of Latinx culture and history that brought together dance, music and poetry at the Educational Center of the Arts on Audubon Street. The following year, he organized “Tell All the Children Our Story,” a community conference with storytelling, music, and workshops that ranged from HIV awareness to gun violence prevention to reparations. He coordinated the event with a whopping 25 community partners, all of whom met at Gateway Community College.

Left to right: Sean Hardy and Rivera before the pandemic, Rivera with his family in October 2020, Rivera with Aleta Staton at a performance before Covid-19. Contributed Photos.

It was during that time that he met Alisa Bowens-Mercado, owner of Alisa’s House of Salsa. When the two were on the clock, he was her partner in crime, working to make sure she provided the entertainment at neighborhood events. When they weren’t on the clock, they were friends and impromptu dance partners. The two called each other “boopsie” as a mutual term of endearment.

When he called her on the lip of her 50th birthday two weeks ago, she turned off her car in the parking lot of a CVS and talked on the phone for two hours. She said she’s so glad she picked up.

“When he met me, he was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re the salsera!’” she recalled between laughs on Friday afternoon. “When he called, we’d be on the phone for two or three hours. He just gave to his community, and he always wanted his community to do better. He was everywhere. He just wanted to show people, especially Latinos, that there’s a world out there. We had a business connection, but we had a very, very deep personal connection as well.”

Every artist he came into contact with became a friend, some of them for life. In the early 2000s, Bridgeport-based artist Ricky Mestre worked with Rivera after landing a show at the Arts Council’s Audubon Street offices. Rivera struck him as refreshingly trusting—he didn’t second guess Mestre when he walked in the door “with a bunch of questions.”

“I wasn’t used to being the one calling the shots,” Mestre said in a phone call Friday. “I remember him saying, like, you have the power all along. He wanted it to come from me. He wanted it to be authentic.”

Mestre took that with him as he mounted the exhibition, for which his mom cooked plates and plates of Puerto Rican food that made the offices warm and fragrant. It stayed with him as he grew his cultural footprint in Bridgeport and New Haven, where he would run into Rivera every couple of years. The last time they saw each other was in 2019, while Mestre was in the midst or coordinating Bridgeport’s annual Pride Month celebrations. Rivera called him "Mr. Socialite," and said that he’d been watching his career blossom from afar.

“He was definitely an awesome person,” Mestre said. “We always stopped when we saw each other. It felt more like it was part professional, part friend.”

Aleta Staton, who is now the director of learning at Long Wharf Theatre, also met Rivera during those years. She had brought a West African peanut butter soup to Audubon Street to share with the Arts Council's staff when Rivera came right over, asking for a taste. They quickly became close friends, bound by a love of food and of the performing arts.

Staton, who lost a younger brother when he was just 14 months old, called Rivera “hermanito” because he was exactly the same age that her brother would have been. In return, he often called Staton his wife, as though they were a family unit. The two fought as lovingly and fiercely as family “about everything,” Staton said—from how they were wearing their hair to what jobs they were considering taking.

“And sometimes I looked at him and wondered, ‘Are you him? Are you my brother’” she said. “We fought and had joy just like family. It was an amazing, amazing privilege for me to be in his circle.”

He was always there, she added. When Staton fell ill last November, he dropped off food on her porch and checked in to make sure she was doing okay. He sent her roses on her first day of work at Long Wharf. The last time she saw him, he brought her a homemade sancocho that had simmered for five hours on the stovetop. At her request, he promised to teach her how to make it when in-person gathering was safe again.

“He was amazing,” she said. “He had a capacity for love that I have never known. I’m still in a state of disbelief. This was somebody who cared so much about every person around him.”

Fellow friends remembered him as equally giving. Berryman first met Rivera in the mid 1990s, and “we would just weave in and out of each others’ lives.” Because both of them were in the arts—Berryman teaches in the city’s schools and plays in its houses of worship—their paths kept intersecting.

The two became very close about a decade ago, when Rivera cooked for an event that Berryman was having with friends. From that point on, they saw each other often, usually with a small group of friends who loved food and fellowship. Berryman was with Rivera at Soul de Cuba restaurant, one of their favorite haunts, the night before he died.

Berryman remained close with Rivera as he cycled through work with Project M.O.R.E., Liberty Community Services, and the City of New Britain. He watched as Rivera worked for himself as a nonprofit consultant, collaborating with fellow artists and community members from all corners of the city. Somehow, he said, Rivera still had time for him. When Berryman got Covid-19 in November, Rivera dropped off soup on his porch. That last night at Soul de Cuba, he and Berryman were planning a trip to Hawaii for the May birthdays in their friend group.

“I’m still, like most people, processing,” he said in a phone call Friday. “We were at a point in our lives where they were weaving back together again. We were really starting to do some wonderful things. It really is a great loss for the arts community. It is a great loss for the community, period … he was always pushing forward. Full of ideas. And I don’t know if anybody else had them. If anything, it taught us to acknowledge the value of people while they’re here, and listen to people while they’re here.”

A longtime educator at Mauro Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School, Sean Hardy was also with Rivera the night before he passed away. The two first met over 30 years ago, but became close through a circle of friends that included Berryman a little over a decade ago. When Hardy had brain surgery two years ago, Rivera made sure he was eating. He checked in on him often. Last month, the two ate dinner at Soul de Cuba two weeks in a row, with conversation that jumped from Rivera’s current work to his upcoming 53rd birthday.

Rivera called him “beloved,” a nickname that was often followed by a command (“beloved, you need to eat something,” he told Hardy after surgery) or more often, a huge smile and hours of catching up between close friends. Hardy said he is still trying to wrap his mind around Rivera’s sudden absence.

“I’m very disturbed by his death,” he said. “He had great plans for the future, and I’m just saddened that those plans for the future won’t be carried out. Having dinner with him one day, and he’s gone the next. He’s gonna be so missed.”

His family is still adjusting to a world that he is not physically part of. At home, Cobián is now caring for her 77-year-old mother. Her son, Rivera’s 17-year-old nephew Nelson, is thinking of the college tours that Rivera was so excited to take him on.

A string musician at Cooperative Arts and Humanities High School, Nelson said that his uncle often pushed him to excel in school. Last year, he encouraged him to join the high school fellowship program at the International Festival of Arts & Ideas. Staton, who was formerly at the Festival, remembered the two as thick as thieves.

“It’s hard,” he said. “I want people to know that even though he had this stern attitude, this intensity, he had a good heart. He wanted the best for people.”