Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts

| The artist during a recent interview. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

The first time Clymenza Hawkins stepped onto New Haven’s Front Street, she had a sense that the city would affect her art. By the time she moved there months later, it already had started to. Now, New Haven is helping her usher in another new chapter in her work.

Hawkins is the artist behind WomenFolk of the UnderGround Forest, a series of fairy—or as she says, faery—folktales retold in collage and photomontage, with modern imagery and strong heroines of color. In each, Black and Native American women populate the frame, some looking out to the viewer while others remain further back, propped amongst lush vegetation, bright trees, and expanses of dark forest.

These heroines are not damsels in distress, but royalty of their own making: they have glowing afros, flowing, long silk gowns, capes that billow and flow as they morph from woman to animal and back. More recently, they have appeared with a series of large and spiky crowns, some fanning out like peacock feathers. There are small collaged works on paper and wood blocks and larger WomenFolk images that occupy whole sections of wall, and stop viewers in their tracks.

Humming just beneath the surface of each are Hawkins’ myriad influences: authors Zora Neale Hurston, Rita Dove, Tony Cade Bambara, Octavia Butler, Oscar Wilde, and James Baldwin, as well as folktale authors and retellings that turn Disney on its head.

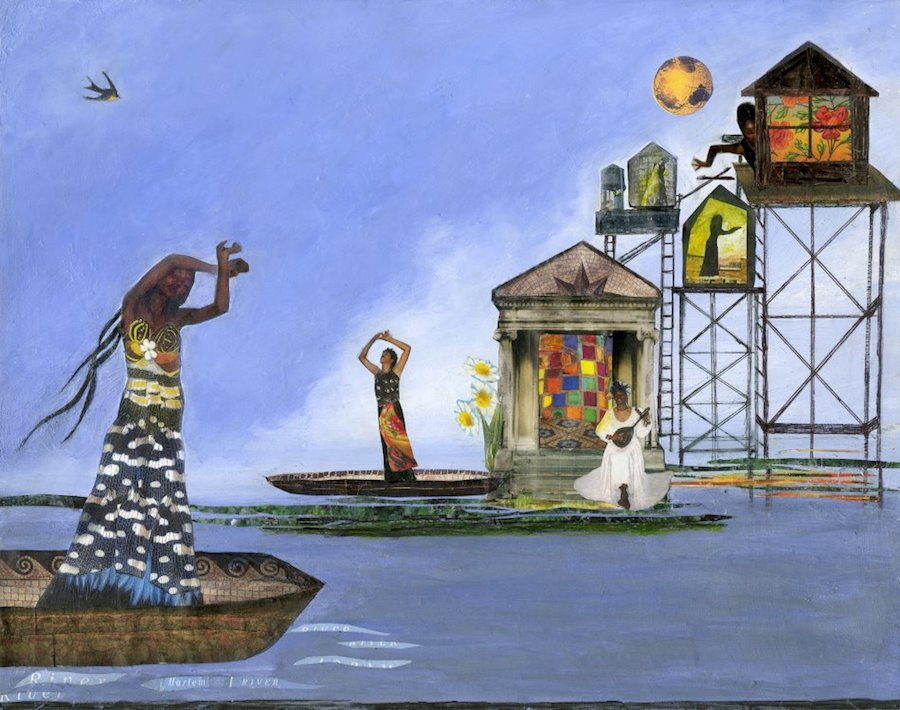

| Hawkins' work Natural Enchantments. Photo courtesy of the artist. |

Several years ago, the artist discovered Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ Women Who Run With Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype, and found in it a revelation (“It was like my bible,” she said of the book). From there, the list grew as she, too, headed in new directions: author Shirley Jackson, singer/songwriter Laura Nyro, and fairy tale expert Jack Zipes, who sent her a signed copy of his volume The Great Fairy Tale Tradition From Straparola And Basile To The Brothers Grimm after she reached out about her work.

Now, she is working on her own book of fairy folktales, as well as large images for her first solo show at Brooklyn’s Welancora Gallery next year. This fall, she will present small collages at Artspace’s annual City-Wide Open Studios in October. Before those lure her into the studio full time, she sat down with The Arts Paper to talk about her time in New Haven, what it means to reclaim narratives, and her take on the #MeToo movement. A selection of that interview is below.

|

Hawkins is working on a series of nudes, some with crowns, that she plans to show during this year's CWOS.

|

I’d like to go to the beginning—why you chose New Haven as a place to relocate after New York.

Years ago, I was still in New York but I wanted to participate in City-Wide Open Studios. They were setting up places for artists like me, who didn’t have space. The “Alternative Space” turned out to be on Front Street, where Fereshteh Bekhrad was the owner of the property. It was more like an artist’s community that she was running on her property.

I was just so … it just grabbed me, the area. It was a street that looked more like Provincetown. I didn’t expect that in New Haven. The yard between the two studio buildings was exposed to the river—it was part of the river. And all I saw was sky. I saw water. And then this space. I was going to inquire about moving there, but it looked like there were tenants there.

So I went back to New York. But I would visit my family in Connecticut [Hawkins is from New Britain], and every time I passed by that area, I’d just feel this pull. So one day, when it was time to move out of New York … my work was growing, and I needed bigger space. So I thought, somewhere in New Haven. I took a trip, went to Front Street, left her [the landlord] a message that I was interested, and just before I reached the train station she called me.

Wow. So did you move right away?

Yeah! It was perfect! Having the river by me, it affected my work. It became part of my work. I did a piece called Harlem River Towers, which is a combination of leaving Harlem and coming to Connecticut, living by the river. Where I stayed [beforehand], that was in Sugar Hill in Harlem. The Harlem River is right by there, so I’m talking about a combination of living between two rivers, and it came out in a piece called Harlem River Towers. Living by the water really inspired my work a lot. Anything dealing with nature.

I lived on Front Street, and it was a place where I did do work and live in a community. There was another artist above me, a photographer. And the river was part of the backyard. Unfortunately, a car crashed into the building and caused a fire. It was a guy being pursued by the police … it crashed into the side of our building, and the top floors just went up in flames.

That was in 2014. Hawkins remained in Fair Haven until earlier this summer, when she moved to a different neighborhood in New Haven temporarily. She is waiting to move into Read's Artspace in Bridgeport later this year.

Sometimes people just talk about having this gut feeling where they just … they can sense a change in their work. Is that what happened?

Well, I knew back in New York that I was selling my work well. I was doing greeting cards (the greeting cards showed women as butterflies), which attracted Erykah Badu to do her live CD cover. But I took a three-year break ... that’s how long it took. I figured that I would take a break from doing my work. I wanted to expand in a different direction, and I didn’t know which way it was going to go.

I don’t want to repeat myself doing the same thing. I see a lot of artists go into a rut and they go into a circle … then they’re not going anywhere. So I took a break. I turned towards writing. I deliberately stopped doing artwork for three years. It took about three years, because I figured I’d find a different direction.

| Harlem River II, Courtesy of the artist. |

Was that hard at all? To just say: "I’m going to leave this all for a while?"

No. Artistically, I still connected to the writing. And then I started listening to what women were saying … what attracted them to the cards [that she was making and selling in New York]. The notecards were photographs I took of my friends, sometimes women I’d see in public and transform them with butterfly wings.

They kept saying they were fairies . And I said to myself “I don’t want to correct them, because they see what they see through my work.” I’m offering something that they see, and they’re telling me what they’re interpreting. It’s so emotional to get them to tell me what they’re getting [from the images]. And they kept saying fairies .

And I’m like: “No! They’re not fairies ! They’re butterfly women!” But then I thought about it. Mostly, in fairy tales, the women are wearing butterfly wings. So I can see that connection. So that started to grow into me … to lead into the fairy folktales. That’s when the idea grew of doing artwork based on the fairy folktales, but from a Black perspective with a modern twist. And that’s when I knew that was the new direction I was going to.

By then, I had joined the Flat Files [at Artspace] … and through Artspace’s auction, I started getting more collectors for my work. There is a little following that developed—they kind of got where I’m coming from, about the fairytale connection. I’m going to start my first volume of fairy folktales and I’m going to create the images for each story.

| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

So how do you feel like you got there?

Well, going back to how the women that were buying my notecards and my art were saying “fairies ." It kind of stuck with me. I’ve always liked fairy folktales. My favorite movie is The Company of Wolves … Angela Carter was the one that started guiding me towards fairy folktales with a modern twist. I don’t think she would have wanted to call it feminist. I think from her point of view view, it was sort of like ... just altering it in the favor of women. These stories have been told so many times, and Disneyfied, that I started doing research.

So now I’m being guided by the women who said that to them, the women looked like fairies . That’s what attracted them. And plus, they look like them. So I took their word, and that grew with me, and then I started doing other kinds of research with fairy folktales. At the same time, I noticed that the media was getting really into fairy folktales. They’re in commercials, they’re in series, they’re all over the place.

It grew into: I’m going to make this group of women, womenfolk or Black womenfolk, of the underground forest. And that was the turning point that this was going to go towards the fairy folktale level. But I wanted to do more research. I wanted to read all kinds of fairy folktales from all over the world.

When I read folktales as a kid, I didn’t see myself [Jewish and disabled], nor did I see women of color represented. You see the skinny princess with the 14-inch waist. I think for a lot of women, that is what they think of when they hear fairy folktale. So where does this come from? Like, was there an outside force that spoke to you, or is it coming from the gut and the heart?

It’s coming from me. It’s kind of this new discovery of finding this other part of myself as a woman and as an artist. It’s saying: “Well, what do you want to say out there?”

Yes. The majority of women that are interested in my work are African-American. But, I’m also pleased to say, it’s not exclusive to them. I’m just speaking for me because I happen to be African-American, and I have some Native American which I acknowledge as well. But as a woman, it’s sort of like of the same thing as Ntozake Shange. She did not want to say “for colored girls” [in her work For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf], she wanted to say “for all women.”

We’re talking about an era then when everything was revolutionary this, Black that, and Black publishing was just thriving. She was saying, "I’m talking from a Black woman’s experience but I’m sharing this with all women, it doesn’t matter what color, they’re going through the same thing." No matter where we are in this world. You know what I’m saying?

A majority of women who have bought my work are African-American. But they’re also European, and white, and that delights me because I don’t want to be categorized. I just feel like the way it was growing, I can say that I’m speaking from my point of view … but put it with a modern twist. Put it with things from African culture, but also from European culture, and also Native American culture. So many rich cultures to embody.

Sometimes, it may surprise people that I happen to be Black. That’s fine. I really don’t want to say “I’m Black this, I’m Black that.” You can see the work, and then when you meet me, of course you’ll find out. I’m coming through my work as a woman, as a Black woman, as Clymenza, and as a visual artist.

.jpg)

| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

I always think of how Zaha Hadid got really angry that people referred to her, over and over again, as a visionary woman architect. Do you feel like that extends to your work—that you’re commenting on and reclaiming these female narratives, but you don’t want gender to be a part of it?

First of all, I’m observing what’s going on with women in the world … I’ll say in this country, but it’s spreading. It’s like, nobody is comfortable being born with what they have. Everyone is altering. Everyone is taking off. Everyone is readjusting parts of their bodies to fit some kind of image that is never-ending. It’s not that it’s new. It just that it’s alarming. It’s overwhelming the culture. Young girls are looking at this at 12 or 13 saying “maybe I need to get a breast implant, or maybe a reduction.” Like, what? This is affecting the young girls.

The other thing is this #MeToo movement. Feminists and women, they will not like me. First of all, we’re not here by ourselves, one-sided. And I don’t believe in the women’s movement because I see they did not support Hillary. Regardless of whether you like her or not.

Now, I don’t know where the women’s movement is. And it’s certainly not the #MeToo movement. Because there’s some kind of hypocrisy going on there. And I don’t go into it, because my whole point is that you can’t live without having a man, no more than a man can’t live without having a woman. Yes, there’s problems, but you can’t work them all out.

.jpg?width=300&name=Clymenza%20-%201%20(1).jpg)

I believe like this. If you have a close relationship with a male, and you understand each other, then he can speak for me. Doesn’t mean I can’t speak for myself. He’s speaking for both of us because we’re in tune. Let him speak for me or order for me, because he knows what I want. I think he’s being a gentleman about it. If somebody can respect your space, and who you are, then there’s no war between a male and female.

There’s women who get into these women’s movements for me, and it’s more like—what’s in it for them? What can they get out of it? And then they try to stretch out that subject that is really making it kind of thin … I don’t join those kind of things. I’m not trying to say anything feminist. I think there’s a lot of artists out there who can do it better, or say it better, than I can. Past and present.

I’m trying to simplify, more in the writing, that there’s value in being independent for yourself. I see so many women scared, like they gotta have a man by their side, which has tragic endings sometimes. Because they're so afraid of being by themselves. I was celibate for like, three years. I told women, they looked at me like I was crazy. I was trying to get to know more of myself, so I won’t make any more mistakes.

I just want to put a different bent on my work. And I’m talking about just putting … I just want to present the fairy folktales with an ensemble of African-American women with a modern twist. Eventually, I will incorporate other women from other parts of the world into the ensemble. Because they are part of the underground forest.

So where does that get us?

With these stories that I’m putting together currently, it’s about how not to be afraid of yourself, how to embrace being independent. You say—me, myself and I. And once you start understanding yourself, you got to root out the bad habits. And it’s an ongoing thing, it’s an ongoing thing.

But what I’m trying to do, through the folktales that I’m doing, it’s about how to have strength and courage to be by yourself. It’s okay. Everything else will come once you understand that. I’m not sure I’m trying to change anybody’s life with that, but I figured through the folktale, it might strike a chord with some women.

I remember on the subway in New York, I was sitting on the train next to this woman. She was Indian, from India, and she was very distraught. She was really upset—she was trying to visit a guy who was avoiding her. He was seeing another woman. And she was saying: “I just don’t know what I’m going to do without him.”

And that’s when I told her. I said: “You’ll be all right. You’ll get over it. The most important thing I can tell you is [that] you shouldn’t be afraid of yourself, to be with yourself.”

And I don’t know if that will stick with her, because when you’re in that state of mind it doesn’t stick. All you can remember is “this guy is not paying attention to me, I need to see him. I need to make him pay attention to me.”

Unfortunately, I’m seeing that not only are women not comfortable with being themselves. You’ve got Black women who want to look like white women. You’ve got white women who want to look like Black women. Who knew? You got European women doing the same thing. Brazil? The most beautiful women? They’re doing the same thing.

It’s like, they’re covering up this natural beauty and they all look alike. There’s so much makeup, and it’s affecting the young girls. They’re too young to even be affected by it, but they are. I’m just seeing women making bad choices with men, with their lives, and they repeat it over and over again.

And they repeat it! Like, “if I wear longer extensions or if I wear my hair color or if I add bigger lips or thin my lips out.” I’m just amazed at what’s going on in this culture! Where is the real women’s movement behind all of this? It seems like they’re weak. I’m not saying they had to support Hillary, but look at what happened to Hillary. Who knew she was up against a rigged election by the Russians and Trump?

I understand that Nasty Women came from what he [President Donal Trump] was doing, and I thought what they did in New York was great. But it’s a bigger issue. The #MeToo movement is a bigger issue, and to me it’s going astray. Because now you got everybody coming from the past talking about #MeToo.

| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

You think that’s a problem?

I’m not saying that it’s not meant to be said out loud. But I feel like this. I have been sexually assaulted when I was young—very young—and it happened to other family members. It’s a lot to deal with. But what I’m saying is, somehow, I didn’t let it ruin my life. I didn’t let it give me a bitter aftertaste. It’s not like I’m avoiding it. It’s just that I don’t want it to run my life, or my feelings.

I know there’s a lot of women who could definitely say “Me Too,” too, but they’re not saying it because they’re saying “I’m not going to bring that past back into my life. I’ve lived my life well since then, that I don’t need to bring it up and bring somebody to justice.”

The justice, to me, is that the person survived and is able to live their life without letting it effectively ruin their life. I understand … I can never be in the place of someone where it’s so bad that psychologically, it may take years or they may never get over it. I get that. I’m just talking about the ones that were able to survive and decided not to join the #MeToo movement because they don’t need to.

They’re satisfied with their life just the way they are. They were able to survive without a #MeToo movement, and they don’t need to jump in in order to say “Me, too” as well. They’re just saying “I am.” And they’re just living on in a positive way.