|

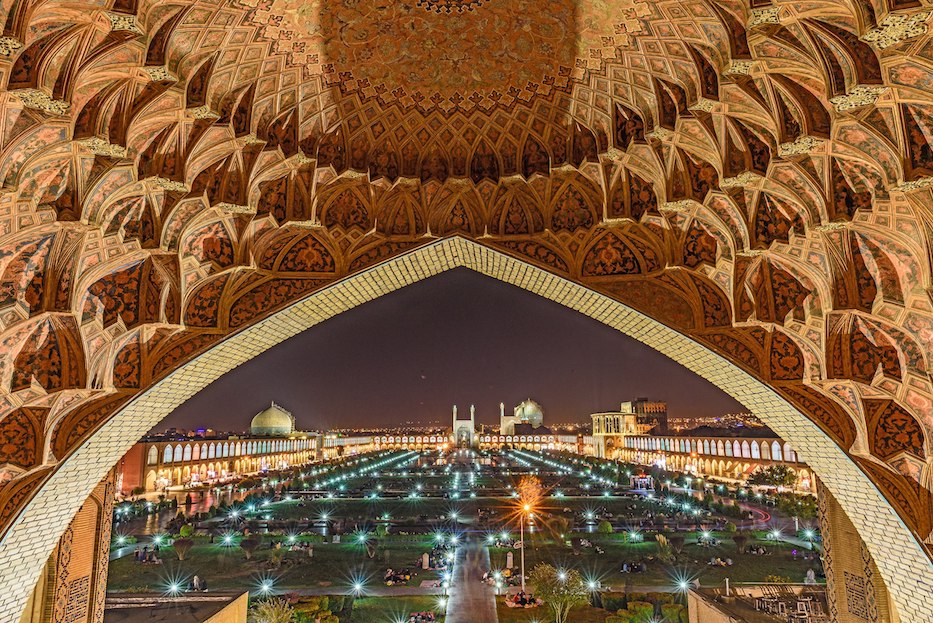

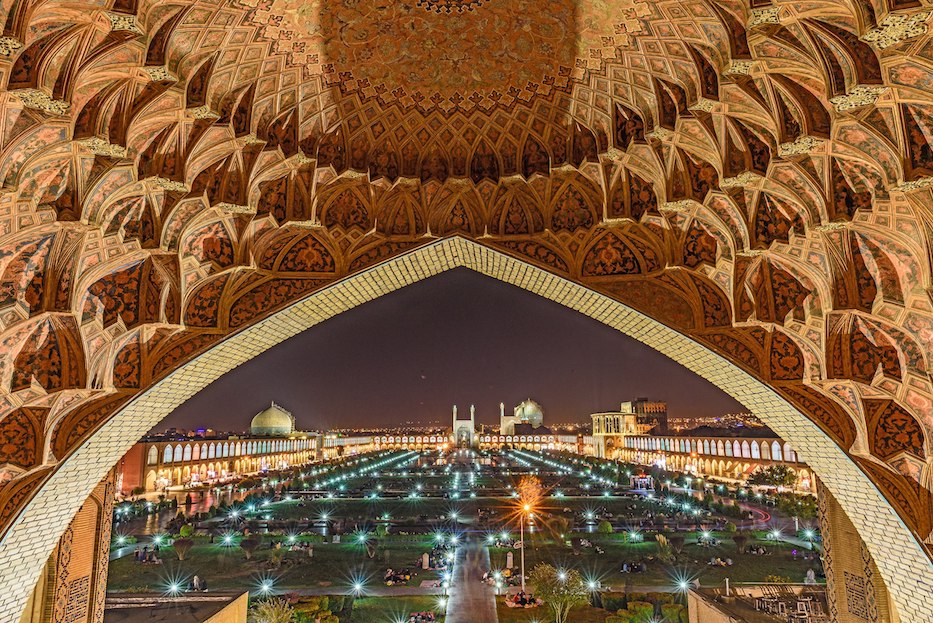

An image from Naghsh-e Jahan Square, which dates back to the early seventeenth century. Keydavoud/Wikimedia Commons Photo.

|

The first to appear was Persepolis, its columns rising from the ground with a grace that has withstood centuries. Then it was Bam, a citadel beckoning in the middle of the desert. Then the great interlocking mosques of Meidan Emam, glittering in blues and greens even from afar.

“Because the President of the United States has decided to threaten to destroy cultural landmarks in Iran (a War Crime by both International and US laws) in retaliation to any action taken by Iran in response to the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, I have decided to spend the next 22 days exploring the 22 cultural sites that are designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Iran,” wrote Patrick Dunn, director of the New Haven Pride Center.

This week, Dunn joined a robust chorus of art historians, cultural preservationists, and concerned citizens responding to President Donald Trump’s threat to target several of Iran’s cultural and World Heritage sites. While the Pentagon has since said that it will not attack the sites—which many have pointed out would be a war crime—it has left defenders of cultural heritage on edge across the globe. The threat comes in the wake of the the assassination of Qassem Soleimani by the U.S.

Some of those voices come from New Haven. Iranian author, poet, and journalist Roya Hakakian, who was one of the founding members of the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center and now lives in New Haven, was one of the first to comment on social media that the “cultural and historical centers of Iran do not belong only to the Iranian nation, but also part of the historical and cultural heritage of human beings.”

Dunn, who was raised between the U.S. and Turkey, said he chose to post one Iranian UNESCO site per day to social media as a way to teach others about the millennia of history at risk—and to learn about some of it himself. He observed a gulf between the American understanding of history and its global reality, noting that there is a distinct violence reserved for the destruction of cultural world heritage. It’s one, he said, that Americans may associate more quickly with the Islamic State than with their own country. He likened it to the targeted attacks of European cultural heritage by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini during the twentieth century.

“For me, it’s a couple of things,” he said by phone in an interview earlier this week. “As someone who grew up in a very historical part of the world, I think a lot of Americans don’t understand what really is at stake when we talk about the destruction of cultural assets in the Middle East, in Asia, in Europe, in Africa. Most of the protected sites in the U.S. are actually natural sites instead of buildings. I think it’s important for people to understand that these things exist.”

“So many images of the Middle East are about war and terrorism,” he continued. “We only talk about Africa through the lens of dictators and famine. We only talk about Asia through the lens of disease and worker conditions. These incredible sites, and yet we don't talk about them. These are the crossroads for world trade in the seventh and eleventh centuries … there are these incredible assets that are so connected to human history.”

Alexander Taubes, whose mother immigrated to the U.S. from Iran, called the threat a terrorist action and “downslide” in the country’s foreign policy. While he grew up in the U.S., Taubes visited Iran as a kid, and remained close to a maternal grandmother who died in Iran at the end of last year. Several of his cousins still live there. Reached by phone, he fondly recalled visiting the country and feeling the pulse of history almost everywhere he went.

“I remember distinctly the mosques and markets, and these incredible cultural sites that predate Islam,” he said. “It’s really disappointing that our president doesn’t share that humanity.”

Their voices are just a few of millions advocating for the preservation of cultural heritage. Earlier this week, The Association of Art Museum Curators responded swiftly to President Trump’s threat, noting that “works of art and material culture are critical to the understanding of our past, present and future.”

“The deliberate targeting of art, architectural, archaeological and cultural sites is not only deplorable, it is also against international treaties to which the United States Government is a signatory, including the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2347 (2017), and 1972 UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.”

Representatives of the Yale Program in Iranian Studies did not respond to a request for comment, but shared an article from Yale Professor Kishwar Rizvi that was published on The Conversation earlier this week.

Reached multiple times by phone and email, Yale’s Institute for Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) declined to comment. During his time at the IPCH, inaugural Director Stefan Simon was an outspoken advocate for the protection of cultural heritage, particularly in the face of rising international terrorism. Current Director Ian McClure did not weigh in. The Yale University Art Gallery, which has over 13,000 objects from the ancient world, said it would be looking into whether it had a statement.