Culture & Community | Arts & Culture

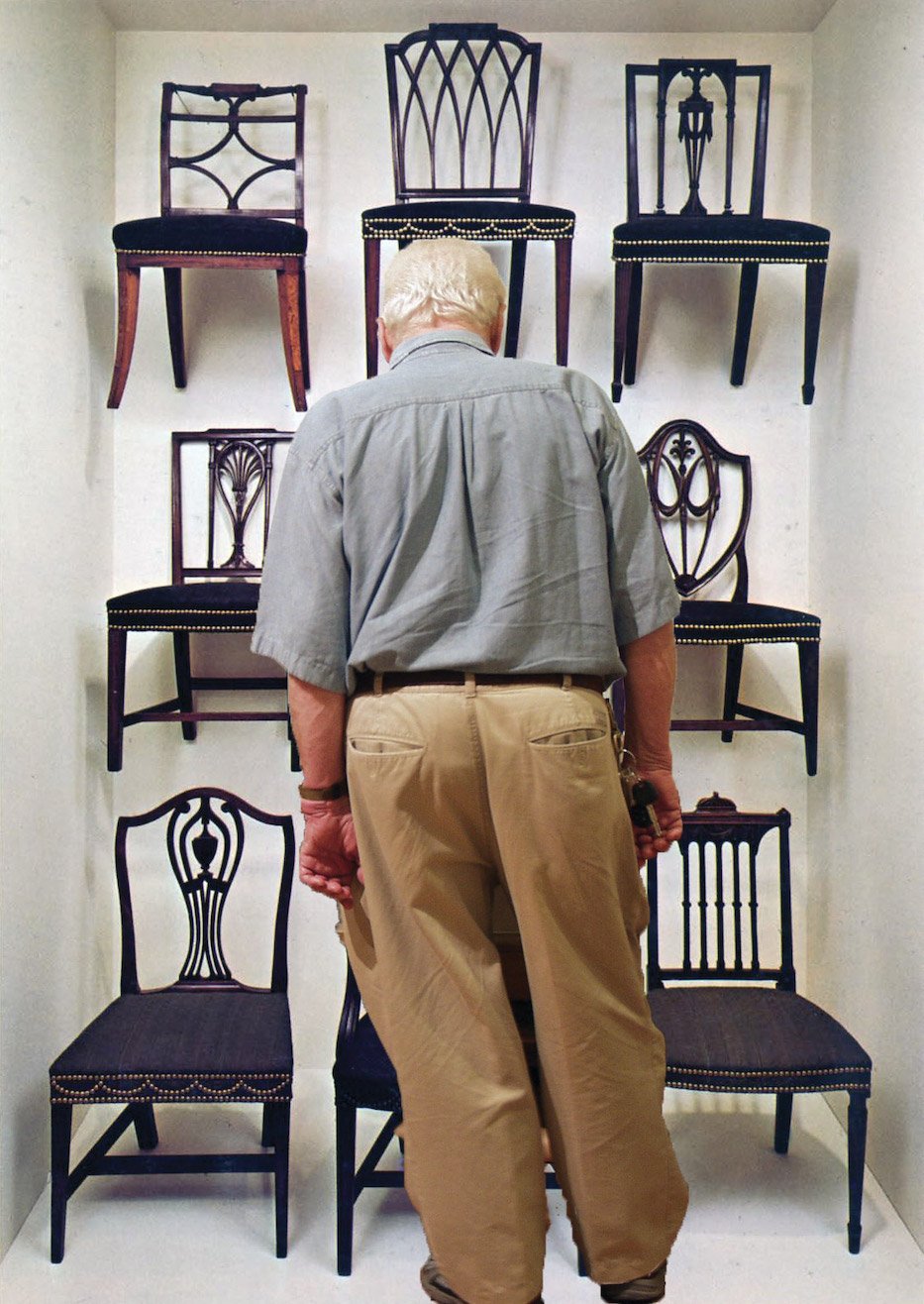

Normand Methot in 2014 at the Yale University Art Gallery Mabel Brady Garvan American Decorative Arts Collection, admiring a reinstallation using his original 1970 system for mounting the chair. The photograph lower in the story shows Methot with Nathan Coste, the first Norm Methot Design Apprentice at the Eli Whitney Museum & Workshop. Sally Hill Photos.

If you ask 91-year-old Normand Methot if a woodworker is a cabinetmaker, a furniture maker, a joiner, a carver, or a carpenter, he’ll have one answer for you: Yes. That he, too, was and is all of those things.

His colleagues, clients, and students might give a slightly different answer—that he is an artist, polymath, philosopher-artisan, and force of nature that is not easily defined.

Methot’s 90-plus years may have dulled his hands and stride, but not his answers to important questions. A woodworker, he’d say, uses wood (over 50 native and engineered species, each with distinct properties), primitive tools and their evolved progeny, and skills to solve problems. In other words, he solves problems.

Born and raised in Fall River, Mass., Methot came to New Haven in 1963 to pursue woodworking. Long before that, his father, a handyman, kindled his love of tools in a basement workshop while he still needed to stand on a wooden crate to reach the workbench. In the town, a neighborhood settlement house’s treasury of chairs in curious styles opened his eye for design. Magazines stretched his horizons and ambition.

By high school, one-third of Methot’s peers had abandoned classroom education for Fall River’s textile mills. Methot, meanwhile, worked his way through the State Teachers College at Fitchburg and returned to Fall River determined to bring modern skills and ambition to shop classes. The timing did not work in his favor: the 1957 launch of Sputnik and ensuing space race changed American education. Investment in college degrees soared; shop classes were drained of resources and respect.

And yet, Methot never abandoned his devotion to teaching. He is a dogged optimist, a seek-and-you-shall-find pilgrim. He admired William Morris’ Arts and Crafts Movement in England, Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Movement in this country, and the Bauhaus Movement in Germany. Each anchored its creative process in handcraft traditions, devising modern designs that could be expressed in industrial production.

In 1969, Methot worked as a technician and took classes in the wood products division at the Yale School of Forestry (it is now the Yale School of the Environment). He soon realized that the creative ecosystem that surrounded the university offered learning more suitable for his temperament than Yale’s formal classrooms and laboratories. New Haven sustained artists, architects, set designers, entrepreneurs, inventors, museum curators, pipe organ wrights, and other pilgrims eager to learn outside of the education-by-degrees box.

He realized that New Haven needed a woodworker devoted to both tradition and experiment, grounded in depression-born practicality, and open to extravagant dreams.

For almost five decades, Methot’s hands built for New Haven: chairs, cabinets, tables, and desks meant to be admired; architectural restorations, furniture repairs, commercial and museum fixtures meant to be invisible. His measure of success, he would tell you if asked, was and is simple. He liked, and still likes, making people happy.

Of equal importance are the values and drive that Methot held and holds dear, which have enriched New Haven’s artisan ecosystem. Many who have never owned or seen a piece of his work have been touched by his influence. Consider, for instance, some basic rules for working and learning that he repeated often:

1. Make yourself invaluable. Methot met Charles Montgomery, a curator at the Yale University Art Gallery, just as Montgomery was preparing to exhibit pieces from The Mabel Brady Garvan American Decorative Arts Collection. Montgomery wanted to mount delicate chairs on walls—to be visible from every angle—without the distraction of infrastructure or support. Methot responded with heroic ingenuity, and Montgomery became a devoted mentor and helped send him to England to study furniture restoration.

1. Make yourself invaluable. Methot met Charles Montgomery, a curator at the Yale University Art Gallery, just as Montgomery was preparing to exhibit pieces from The Mabel Brady Garvan American Decorative Arts Collection. Montgomery wanted to mount delicate chairs on walls—to be visible from every angle—without the distraction of infrastructure or support. Methot responded with heroic ingenuity, and Montgomery became a devoted mentor and helped send him to England to study furniture restoration.

2. Cultivate allies. Methot collected finishers, electricians, plumbers, sheet metal workers, machinists, movers and cleaners whose skills and values he admired. It became a community of mutual support. He expected loyalty and reciprocated respect. Should you introduce yourself to one of his people—Norm gave me your name—even small requests got generous attention.

3. Collect tradition—boldly. Methot’s shop evolved in and around an 1895 Carriage House on Elm Street. The actual work area was well equipped, but small. Adjacent barns and basements accommodated his extravagant passion for collecting history: boats to be rebuilt, disassembled barns, chair relics rescued on bulk trash days, myriad abandoned doors that documented a century of style and construction, and countless picture frames.

The improbable certainty that his collection would have a desperately-needed-thing was legendary. He would explain to the incredulous: You wonder why I collect? Because you are here for it! If you need it, it's valuable. The usual, informal price: a six pack of beer.

4. Collect with honor and respect. Methot insisted that collecting required sensitivity and discipline. “When a widow offers you the contents of her husband’s workshop, don't grab what you need,” he would say. “Take what she needs—take everything. She wants to believe that every jar of mixed bolts had meaning and value. She wants to remember your respect.”

5. Manage your shop. Don’t let your shop manage you. Workshops crave organization, reorganization and cleaning. Remind yourself daily that the primary obligation of a shop is to get billable projects out the door. Structure your maintenance projects and time strategically—more as a reward for finishing a project than a condition for getting started. Otherwise you’ll never get started.

6. Embrace new tools across boundaries. Methot was born less than a year after Thomas Edison died. Electric tools came to the trades in his lifetime. The first cordless tools arrived in 1978. Some traditional artisans were skeptical. Methot saw the agility that battery-powered drills gave to the early-adopter set builders at the Yale Repertory Theatre and asked, “Why not?” The lesson? Expect and celebrate change.

7. Share knowledge. Before the internet and forwardable links and videos, countless trade magazines explored every facet of the built environment. Think: Fence and Gate Builder, or Custom Door Construction. Methot devoured these. He scribbled page numbers of relevant articles or ads on their glossy covers with a black sharpie, then dropped them into mail boxes or truck cabs on his early morning route to work. He knew what people needed to know.

8. Speak your piece. Before email, most evenings Methot clacked away at a manual typewriter. He was a snail mail influencer. He wrote to politicians, customers, suppliers, and colleagues—with congratulations and complaints, questions and suggestions. Because a letter puts your thoughts in their hands, he might say. To his less forthright peers he would say: If you do not speak, you cannot complain that they do not listen.

9. Show up. Normand attended art openings, lectures, concerts, and Yale opera recitals, often in workshop attire. His belief, I like people to notice my work – it seems only fair to applaud the work of others. He prodded colleagues to join him.

10. Experiment beyond horizons. In I976, University of Illinois-Champlain researchers designed a super-insulated house that provided year-round comfort with no furnace. For recreation and curiosity, Norm bought two dilapidated cabins in Vermont and reconstructed them to test the designs' effectiveness … because 1980 seemed a good time to begin doing something about climate change. His report? “Well, they kept me warm.”

11. Give back. You don’t have to be rich to be a philanthropist. For many years, Methot traveled with other artisans to Haiti to spend a week restoring or building community infrastructure. They sent a shipping container of tools and materials in advance to support the work. His report: Sharing your skills and sweat is giving that is easily received.

12. Invest in others as others have invested in you. Methot was a creative and proactive mentor—an elder statesman in the New Haven trades, a coach for young entrepreneurs, a matchmaker who launched productive partnerships, an advocate for emerging artists.

He shared his experience as a case study that there are many ways to build a career which is useful, satisfying, challenging and rewarding. He has been known to say to an engineering student desperately restless in calculus classes – Have you got a couple of hours? Get in my truck. I know a boat building school in Rhode Island that just might be the place you need. It was the right place.

13. Take Notes. Life is complicated. Norm carried 3x5 cards and a pencil—always. And he expected others to be equally prepared.

On August 18th, to celebrate Norm’s 91st birthday, his daughter Nicole, Peg and John Sancomb, Sally and I, shared his favorite coffee ice cream cake with him. As we sat down, reflexively, John and I put our 3x5 cards on the table. Norm smiled. We took notes.

Bill Brown directed the Eli Whitney Museum from 1988 to 2020. He considers the core of the Museum’ work – its Apprentice program and 600 Apprentices – a direct extension of Norm’s teaching. The Norm Methot Design Internship honors his devotion to teaching. Mr Methot still sits on the Museum’s Board of Directors.