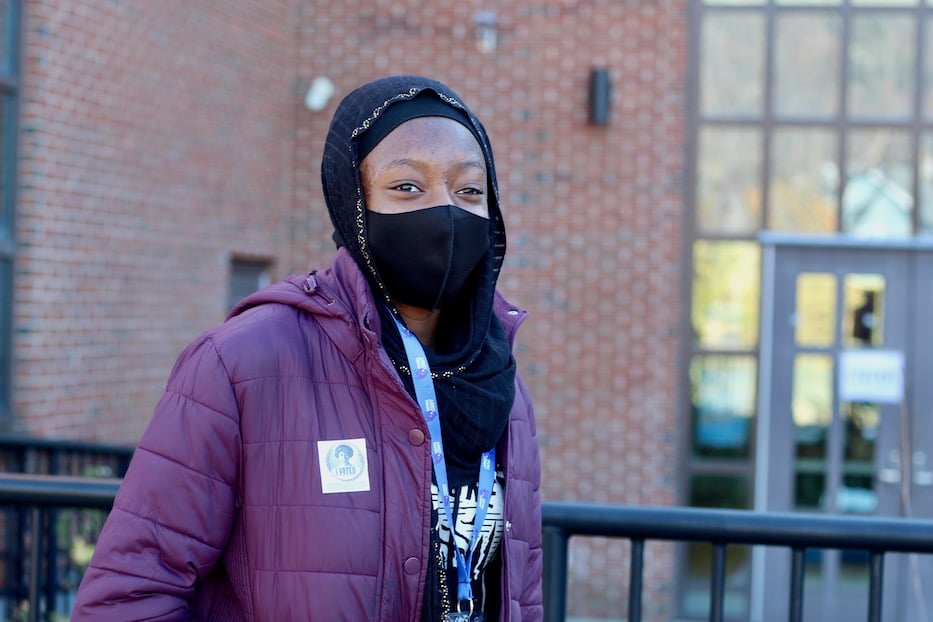

“The argument now is like, human rights are debatable. I just don’t think that’s the case," Biao said. Lucy Gellman.

Abiba Biao slipped her ballot into the voting tabulator at Mauro Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School—and became a first time New Haven voter just hours after turning 18.

As she did, she got a snapshot into some of the hurdles that stand between young, progressive voters and voting itself, from registration and voter literacy to the candidates.

“I wasn’t even gonna vote today,” said Biao, a freshman at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU) who has written for the Arts Paper and the New Haven Independent, and is leaning towards a major in public health. “I just don’t feel represented. I don’t feel like I have options. Since Connecticut’s really Democratic, I didn’t feel like my vote would really count. It would still stay the same.”

Her journey to the polls has been a long and sometimes tenuous one, where the world that exists is sometimes at odds with the world she wants to see. The eldest child of Togolese immigrants living in New Haven, she’s never thought of herself as especially political, she said.

As a kid, her studies at Barnard Environmental Magnet School instilled in her an early love for the environment—but nothing seemed divisive about the horseshoe crabs she watched scuttling through the Long Island Sound. At home, she was a doting sister to her two younger brothers. At school, she excelled in her classes. When she headed to Achievement First Amistad High School, she became a member of the New Haven Climate Movement, but didn’t think of the work as explicitly tied to voting.

Tawana Galberth explaining the voting process to Biao. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Meanwhile, she was watching as the country drifted toward two political poles, a trend that she still finds disturbing. Biao was a sophomore in high school when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, sending classes online overnight. Then that May, George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis Police, catalyzing a summer of protest across the country and in New Haven. Biao, whose parents forbade her from marching because of Covid-19, began thinking about how she could use her skill sets to fight for what she considered basic human rights.

Last year, she became the communications director for Students for Educational Justice. She watched as Amistad students protested sexual harassment with a walkout at the school, and started thinking about journalism as a way to amplify young voices. Then this March, during her senior year of high school, Biao began working on graphics for Kate Farrar, a democratic state representative who is up for reelection in West Hartford.

Watching Farrar door knock, Biao saw firsthand what it meant for a state legislator to care about their constituents, she said—but she didn’t feel like she had ever received that kind of attention in New Haven.

"I feel like the Democrats are similar to the Republicans in the sense that they are not advocating for change as well as they should be. It’s very complacent. It’s very slow,” she said.

“The argument now is like, human rights are debatable. I just don’t think that’s the case.”

Still, she wasn’t sure she would vote, she said. For months, she’s known that her 18th birthday falls on Election Day—but she didn’t register until the afternoon of Nov. 1, the deadline with the Secretary of State’s Office. She was disappointed by the lack of “alternative parties” that she saw on the ballot, she said. Even as she covered campaign events for Gov. Ned Lamont in New Haven, she remained lukewarm on the candidates. She didn’t like the vitriol she saw during campaign season, she added—and often felt that it came without substance.

But as Tuesday inched closer, she decided to come out. At SCSU, she is already interested in public health as a path to racial justice, including the recognition of racism as a public health crisis. She understands that who sits in the state legislature—and represents her in Congress—is part of that.

Biao inside with Kassandra Rowe. “You don’t vote, then technically, you’re getting these bad officials elected by your absence of voting," she said.

“You don’t vote, then technically, you’re getting these bad officials elected by your absence of voting,” she said. “Which isn’t what we want to do, but at the same time, I don’t think that Democrats are doing a good enough job. Which is why I was like, meh.”

At first, Tuesday reaffirmed that skepticism, she said. Following a sign on Mauro Sheridan’s front doors, Biao headed to a driveway on the left side of the school, where red and blue painted stars sat scattered across the pavement. But when she reached a side door, it was locked. Inside, the lights were off. So she headed to the driveway on the right side of the school, puzzled until she spotted the familiar blue-and-red sign to vote.

As she rounded the corner into the parking lot, something changed. Beneath a small tent, Ward 27 Co-Chair Andrea Downer raised her arms in a kind of greeting. Walking over to Biao with lifelong New Havener Tawana Galberth, Downer greeted her eagerly, asking where in Upper Westville and Amity Biao lived. “We’re neighbors!” she exclaimed when Biao gave her street and address.

“This is your first time coming out voting?” Galberth said as Biao nodded along. “It’s important that we feel that we make a conscious decision to who we are electing.”

She lifted a flier outlining the Democratic-endorsed candidates across the state, going one by one (“We got Gary! We gonna win with him!”) until she had reached the end of Row A. She talked Biao through question one, an amendment to the state constitution that would allow for early voting. She chatted with Board of Alders Majority Leader and Amity/Westville Alder Richard Furlow, who urged her to head into the polls. It was just after 1 p.m., and she was ready.

Inside, poll workers Kassandra Rowe and Cynthia Williams had good news for her as she fished around for her ID: her SCSU badge, which hung on a lanyard around her neck, would do. Holding her hand out, she received her first-ever ballot. Less than two minutes later, she was feeding it into the tabulator.

In an interview afterward. Biao said she's still warming to the process. As a young Black woman and an activist, she’s seen how white supremacy—and white people—work to undercut and disenfranchise Black people, and non-Black people of color in and beyond the U.S. She was excited to see people who looked like her, whose lived experience overlapped with her own.

“I thought it was just gonna be a bunch of white people, honestly," she said. "When it comes to being politically active, you don't always see BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Color] people. So it was nice—the rundown, how she was explaining everything to me. It felt familiar and it felt more comfortable."

“I feel like voting should be much more accessible than this,” she added. “I mean, would I vote two years from now? We’re gonna see about that.”