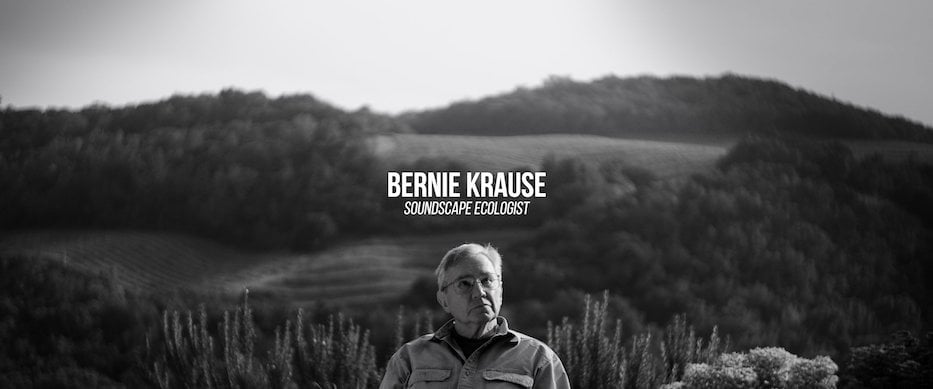

The Last of the Nightingales Photo.

If you asked Bernie Krause: "If a tree falls in the forest, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?" his answer would be an emphatic yes.

A musician and self-described “soundscape ecologist,” Krause has spent much of his life studying the unique acoustic signatures of different environments, recording thousands of hours of tape and amassing one of the largest environmental sound libraries in the world. Sound, for Krause, is an under-explored medium for thinking about how the planet is changing—to imagine a sustainable future, it’s worth just closing our eyes and just listening for a moment.

“While a picture may be worth a thousand words, a soundscape is worth a thousand pictures,” he says.

Krause’s story is told in Masha Karpoukhina’s short documentary The Last of the Nightingales, which screened at the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) on Thursday as part of NHdocs, the New Haven Documentary Film Festival. The film was shown as part of a series of five shorts on the topic of art, the environment, and sound design.

The festival runs from Oct. 12 to 22 at several locations across New Haven and Hamden, including Cafe Nine, Witch Bitch Thrift, the Stetson and Ives Branches of the NHFPL, Best Video Film & Cultural Center, and The Cannon, among others. Tickets, screening times, and more information are available here.

For Krause, the earth’s soundscape can be divided into three categories. The first, geophony, describes the sounds that emanate from abiotic features of the landscapes—the creaking of glaciers, the rushing of water, the whistle of wind. These were the first sounds to occur on our planet. The second, biophony, includes the sounds of living organisms, like the chirping of birds or the swishing of a school of fish.

Anthropophony is the final mode of landscape sounds, representing the range of human-made noises that fill the atmosphere. Airplanes roar overhead, construction equipment clanks, and refrigerators emit a low, persistent hum that is hardly even noticeable until it comes to a halt.

As we descend further and further into a warming world, Krause explains, biophany is becoming increasingly quieter while anthropophony takes its place. In the film, he draws attention to a series of soundscapes that he has revisited over the years, demonstrating the frighteningly rapid progression of this trend.

In one striking example, he plays a pair of recordings of a California forest before and after it was logged. A symphony of birdsong fades into the knocking of one lone woodpecker.

“Our planet is becoming irreversibly quiet, and this is frightening to me,” Krause says.

Filmmaker Duane Bruton in conversation with Margaux Diebold. Kapp Singer Photo.

Krause began his early career as an electronic musician and composer in Hollywood. He was prolific, writing music for over 135 movies, and laid the groundwork for the use of the synthesizer in popular music and film scores. His first experience collecting sounds of the natural world came in 1968, when he was working on the electronic music album In a Wild Sanctuary with Paul Beaver. From that moment on, he began obsessively recording in the field.

As much as The Last of the Nightingales introduces a new way of thinking about how humans confront the environment, perhaps its most compelling aspect is the deep, intimate window into the life of Krause himself. The vast majority of the film is made up of a simple, straight-on interview with Krause outside his northern California home—intercut with dramatic landscape shots and stunning 3D animations of audio waveforms—and over the 32 minutes, one feels like they really get to know him.

“If I could do one thing to get people to listen, I would tell them to just shut the fuck up,” Krause says with a chuckle at the end of film.

In fact, the strongest point of many of the shorts screened on Thursday were detailed portraits of their respective main characters. While each piece offered new perspectives on the intersection of art, the environment, and sound, none lost focus of the individuals driving each story.

Joy, directed by Aner Etxebarria Moral, tells the story of Joy Nyakagezi, a ranger in Uganda’s Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, who becomes fascinated with the social lives of a family of gorillas whom she protects from poachers. And in Island of Pete, filmmaker Duane Bruton showcased the life of Pete Raho, a weird, chaotic, and endearing Brooklyn-based artist and audio engineer whose small apartment is overflowing with his creations.

“I wanted to know what made this guy really tick,” Bruton said in a question-and-answer with the audience after the show. “There’s something underneath there that I just wanted to keep diving at.”

“I’d ask him the same thing in multiple ways, in different environments,” Bruton said of his process for making the film. “From there I took all those questions and answers and I storyboarded it and mapped it all out.”

“This story is really about a guy trying to make something in the world.”