Faith & Spirituality | Music | Arts & Culture | Musical Theater | Community Heroes

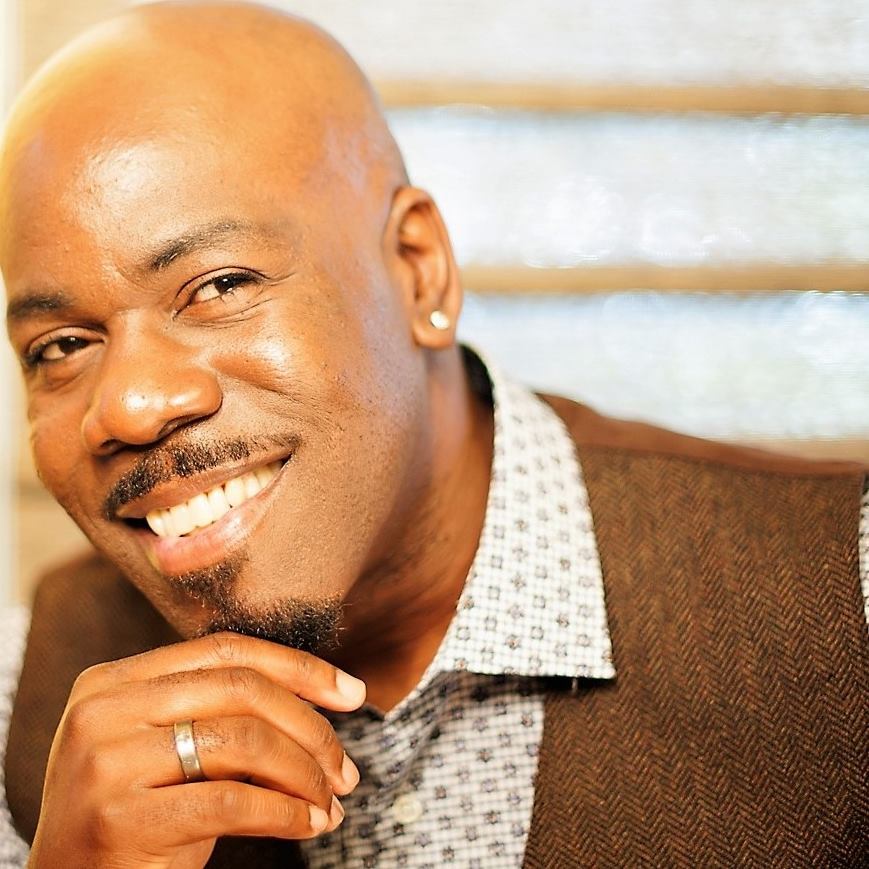

Brown in 2017. Contributed Photo.

You can’t see Charles Brown in the frame, but his voice is the first thing you hear. On the risers, members of the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers begin to sway, one foot, then the other. Piano rolls beneath them. Then the voice, like a bolt of pure silk: How to-o reach! The masses! Men of ev'ry birth/For an answer! Jesus gave the key!

The sound climbs, smooth and sweet. The choir answers in perfect harmony. Brown begins to belt, and everything but his voice fades away.

In the month that the world has kept turning without him, friends, family, and fellow vocalists have continued to keep his memory alive in fellowship and in song.

Brown was a beloved son of New Haven, triple-threat actor who graced Elm City dance studios and Broadway stages, and the first music director of the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers. He died unexpectedly at home last month in Landover, Maryland, where he was the vocal director for the five-campus, 10,000-member Zion Church.

The family does not yet know the cause of death. He was 58 years old.

“His whole life was built around the music,” said his mother Mae Gibson Brown, co-founder of the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers and an associate minister at St. Matthews Free Will Baptist Church, in a recent interview at her Orchard Place home in New Haven. “I have to believe that he was sent here for an assignment, and in some way he had finished his assignment.”

A Rising Star

Sheila Bonenberger and Mae Gibson Brown, who co-founded the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers at Gibson Brown's home in January 1985. Chuckey Brown was the music director until 1989. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Brown’s path to the arts began when he was just a baby, the youngest child of six in a Winthrop Avenue house that was always filled with music. By the time he was born in November 1963, his mother had been lifting her voice in praise for decades, from a childhood in segregated West Virginia to a move to New Haven in 1954. Even as a baby, her son made an entrance, at 23 inches and almost 10 pounds.

His mother discovered that music soothed him, and became a language between the two of them. When he cried, Gibson Brown often lifted him to her mouth and sang with her lips on his, so close he could feel the vibration of her voice. “His little eyes would light up” and he would calm down instantly, she remembered. It was the beginning of a life lived in song, often in service to a higher power.

Once he could use his voice, he didn’t stop. Even as a young student at Foote School, “he was different,” Gibson Brown remembered. "He always looked at things different than most children, I think."

Brown—or Chuckey, as most people knew him—was insatiably curious, from his insistence that Adam and Eve didn’t have belly buttons ("they were not born, they were created," he informed his mother when he was four or five) to the way he would puzzle over grammar, rearranging song titles out loud. As soon as he could walk, he was drawn to the school’s piano, on which he happily banged just to hear the sound come out. It wasn’t long before his family had one at home, too.

“His brain has always worked in a different way,” Gibson Brown said. The whole family was musical, and her baby boy happily slipped into the role of pianist when they played at home and visited churches across the city, Brown on keys and his older brother John on guitar. When he was still young, he was short enough that he had to slide his body along the piano bench, touching the pedals with his toes. He played and sang up until the week that he passed.

Wherever he went in New Haven, it seemed that his outsized and sweet personality often preceded him. At home, he and his older sister Janet (now Janet Brown-Clayton, the executive director of Highville Charter School) were inseparable. “I gave birth to Chuckey, but you would have thought he was her baby,” Gibson Brown laughed as she spooled through memories earlier this month. In elementary and middle school, the two sat for hours in Janet’s room, their French homework laid out around them as they prattled back and forth in this new, shared secret of a foreign language.

That generosity extended to his peers. As an eighth grader at the city’s Augusta Lewis Troup School, Brown helped tutor fellow students in math. Marcella Monk Flake, who attended the school during those years with Janet, remembered him during that time as “New Haven’s little brother.” It became part of a friendship with the Brown family and their matriarch, whom Monk Flake fondly calls “Ma Brown,” that would last for over four decades.

In the 1970s, Brown’s star was rising. At 14 or 15 years old, he was directing the choir at St. James Unity Holiness Church, where people would pack the Lawrence Street sanctuary on Sundays just to see him conduct and sing. During the week, he was a student at James Hillhouse High School, where he joined the school’s chorus and then-robust gospel choir, became the school’s first male cheerleader, and stepped up as drum major for All City High School Band. At night, Gibson Brown knew he was home when she heard him his voice rising in song off Whalley Avenue as he turned onto Winthrop.

Dr. Edward Joyner, who was Hillhouse’s assistant principal during the time, remembered Brown as “clearly a phenomenal talent.” Joyner first met Brown years before he graced Hillhouse’s halls and stages, first through his father John and again through several of his older sisters. Before Brown got to Hillhouse in 1977, Joyner had taught his older sister Alyson, and mentored his older sister Janet.

In Brown, he saw an artistic dynamo whose spirit glowed. During his tenure as assistant principal, Joyner “always tried to make sure the arts were front and center,” and often scheduled talent shows, class nights, fashion shows and performances for the student body. He remembered working with teachers to schedule a run of The Wiz in which Brown played the scarecrow, helping to carry the show. At another talent show, he offered to duet with Brown on “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday.” Cooley High, the film that made the song famous, was only a few years old.

It was a hit. When Brown crooned the solo from the stage, it became easy to see why his voice was later called “liquid gold” by his colleagues in Maryland. Joyner sang from the pit, so as to stay hidden. Afterwards, “the kids said: ‘How did he sing both of those parts?’” Joyner remembered with a laugh. He knew that Brown was destined for stages beyond New Haven, and later cheered him on as he landed parts in RENT, Miss Saigon, The Lion King and Starlight Express on and off Broadway.

Because their families are close—“not related by blood but they are closer than that,” he said—Joyner saw Brown and members of his family as recently as last Thanksgiving, as they ate together beneath a large tent in Joyner’s backyard. “I’ll see you at the next holiday,” he remembered saying as he and Brown embraced. It was the last time they saw each other.

“Chuck has a special place in our family’s heart,” he said in a phone call Friday afternoon. “He gave more to the world than he got out of it.”

Outside of the classroom, Brown poured himself into both choral conducting and contemporary, lyrical and African dance. He was affiliated with dancers at the now-legendary Bowen-Peters School of Dance and, after it opened on Edgewood Avenue in 1980, Dee Dee’s Dance and Fitness Center. Shari Caldwell, who taught with him at Dee Dee’s, remembered how he quickly became known as “the stallion,” for the grace with which he moved.

“He was just beautiful,” she said. “His form was just beautiful, his movement was as beautiful. He was a magnificent dancer, and he was an even better vocalist, singer.”

He and Caldwell both began to train with the dancer Paul Hall, who ran a contemporary dance company in New Haven until his own death in the late 1990s. “They were brothers with different moms,” Caldwell remembered in a phone call last Wednesday. Before he finished high school, Brown accompanied Hall to New York City, where both of them tried out for a summer institute with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. He landed a spot, one of just 15 students selected from over 1200 auditions.

By then, he was already talking about heading to Broadway. In the four years before he did, Brown continued to transform New Haven’s musical landscape. Hall and Brown joined Mikata, the Afro-Caribbean, funk, and Latin-infused brainchild of Richard Hill and Jeff McQuillan, and wrote music for one of the group’s early albums. He directed multiple church choirs around the city, including a 20-member ensemble at Varick Memorial A.M.E Zion in Dixwell.

His cousin Aleta Staton, now director of community engagement at Long Wharf Theatre, remembered being in the group, and knowing that every member was hanging on to his every word. He was exacting but also gentle, more certain of what members were capable of than they sometimes were themselves.

“He looked in my eyes and he whispered, ‘Deliver,’” she remembered of one performance at Varick. “And I did. He got work out of us. There were about 20 of us, and I was very lucky that he let me sing. I learned so much under him.”

Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers: “The Ministry Of The Music”

That time was also the beginning of the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers. In October 1984, Gibson Brown met Sheila Bonenberger at the Wightwood School in Branford, where she was an educator for 48 years. Bonenberger, who is white, had heard Gibson Brown singing with her children at a potluck. She wanted to learn how to do what she had just heard. Gibson Brown gave her a tentative “Yes."

The next time they gathered, it was at Gibson Brown’s home in Beaver Hills. Bonenberger and two fellow “salts”—that’s what the choir calls white people—listened carefully as Brown taught them the gospel standard “Encourage My Soul.” He ran through each of the parts with precision, exacting as he worked through them in real time. There was no sheet music, no anxious rustling of pages. The group learned the parts aurally—a central tenet of gospel music—and sang. In a single room, something magical happened.

“At the end of that, he looked at us, and we all looked at each other, and we were electrified,” Bonenberger said in a recent interview, sitting across the room from Gibson Brown. “And he said, ‘Let’s do this again.’ I will tell you that I have never known anyone more charismatic and more extraordinary as a musician and as a teacher than Chuck.”

The Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers started small, with just a few members and bookings at a few churches and community festivals across the greater New Haven region. In its early years, Brown became the de facto director, bouncing from the keyboard to the front of the choir at weekly rehearsals and concerts. In early videos he is trim and tall, sometimes airborne as he conducts the group. His whole body moves with the music, as if the song is inside him, crackling hotly from his feet to his head on its way out.

Multiple members saw him as a musical alchemist. Whatever people thought they could do, Bonenberger said, Brown would instantly pull out more. If he was severe—and he could be—it came from a place of trust in something bigger than the choir. As the group grew from five members to 12 to dozens, “I knew that I was in the presence of someone who was a complete musical genius,” she said.

Soon, audiences did too. In December 1986, the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers competed in the fourth annual New England Choir Festival at the Shubert Theatre and won. They went on to perform at potlucks, churches, theaters, senior centers, schools and prisons for the next three and a half decades, before Covid-19 created an unwelcome hiatus from which they are just coming back. In a recent interview, Bonenberger pulled out a 50-page archive of performances, from the New Haven Green to the Apollo Theater in Harlem.

Sometimes the choir was welcomed with open arms, Bonenberger said. Sometimes it took the audience longer to warm up. Brown and his mother always gave the choir the same direction: they were there to minister. If they did it from their hearts, nothing else mattered.

Rev. Harlon Dalton, who is still a member today, said he thinks of the group as revolutionary because it represents “racial integration on Black people’s terms.” He first heard the singers perform at a church in 1985. At the time, Dalton “had been unchurched” for roughly two decades, since leaving the home where he grew up as a Baptist. Hearing the singers stirred something deep within him.

“It served as helping me connect all parts of myself,” he said. He would go on to write a book entitled Racial Healing, in which he dedicated space to the choir, and become the missional priest at the Episcopal Church of St. Paul and St. James in Wooster Square. Once he joined—the group performed at his wedding in 1986 and the rest was history—he saw for himself the magnetism with which Brown worked.

“I really watched him develop, pay attention to his craft, and help other people maximize their potential,” Dalton said in a phone call earlier this month. “He knew how to conduct a choir, and how to lead.”

Nowhere, perhaps, was that truer than the prisons in which the group performed, including several that it visited on road trips out of the state. In 1985, the choir had its first performance at Somers Prison in Enfield. A few years later, singers found themselves at York Correctional Institution, the women’s prison in Niantic. Dalton remembered watching Gibson Brown step forward to minister as the group sang.

“The spirit in the room—the small ‘s’ and the capital ‘S’—was almost overwhelming,” he said. “I don’t know if they specifically offered hands, or asked women to come forward. And the guards started to come forward, and Mae just made a gesture, and the guards, they kind of backed off. And Mae continued to put her hands on these women, and we continued singing, and it may have been the most powerful religious experience I have ever had.”

During those years, Brown shared the piano with Ronald “Ronnie” Pollard, who later became the group’s director. Pollard first heard the singers at a family reunion in New Haven in 1985, when there were only about a dozen members. He was living in West Virginia at the time, and soon moved his whole family to Connecticut. When he applied to join the group in 1987, he didn’t let on that he also knew how to play piano. “I was like, ‘I want to just sing with a group, I just don’t want to have to play,’” he said.

But Pollard's cousins liked to gossip, and word of his skill got out. After learning that he could play piano, Gibson Brown put both Pollard and Brown on keys; the two sometimes switched in the middle of a piece if the music demanded it. During a performance at Somers Prison in 1989, Brown started at the piano bench, and then stood up and let Pollard take over. It was flawless. Pollard has since directed the group for over 30 years. He sometimes shared the stage with Brown, who returned to conduct a 2017 performance of the Salt & Pepper Gospel Singers at the International Festival of Arts & Ideas.

“In all God’s wisdom and knowledge that everything happens for a reason, I just believe that he placed me in that spot at the right time,” he said. “When I’m playing for the choir, I’m not singing or playing just to try to show off. It’s the ministry of the music. You’re out singing gospel music, which is the good news of Jesus Christ.”

To Broadway, & To Zion

When Brown turned directing the choir over to Pollard in 1989, it was to pursue his own dreams as C.C. Brown on Broadway. In 1993, he went to Las Vegas to preform Starlight Express on roller skates. He moved back to New York, where in 1995 he landed the role of John in a touring cast of Miss Saigon. The following year, he landed the role of Tom Collins in the first national tour of RENT. In fuzzy, technicolor videos of him performing, he is transcendent, his voice lifting up the whole show like the whole stage belongs to him.

When the show opened at Boston’s Shubert Theatre in November 1996, Hartford Courant reporter Malcolm Johnson went to see it, and praised Brown’s solo in the reprise of “I’ll Cover You.” Brown “rocks the house,” Johnson wrote. It was a work whose gospel core seemed like it was made specifically for him. Brown himself talked about delighting in the role, in which his character meets and falls for the gender-bending Angel Dumott Schunard.

“RENT is about the power of love to right wrong and the power of friends who stick together," Brown told Chicago Tribune reporter Sid Smith when the show traveled to the Windy City in 1997. "Don't tell me it can't change people's minds or their lives."

Actor Evan D'Angeles became the first Filipino Angel during those years, when he joined the touring cast of RENT in 1998. As part of the Broadway cast of Miss Saigon in the early 1990s, he knew who Brown was—including “the richness of his baritone” that he had cultivated in New Haven’s churches and schools. D'Angeles was struck by how deeply Brown understood Collins, whose capacity for sorrow was outdone only by his ability to love.

On the road, Brown “was the poppa figure” of the bunch, D'Angeles said in a phone call Sunday night. On stage, he was a force. D'Angeles, for whom the role was his first stage kiss, remembered how Brown could envelop him at the end of “I’ll Cover You,” that bouncy, pop-flecked number in which Tom and Angel declare their love for each other. His whole body shook when Brown performed the reprise to “I’ll Cover You,” sung at Angel's funeral after she has died of complications from AIDS.

“It was a pleasure to fall in love with him every day,” he said. “It was an honor to fall in love with him daily. Every time … he just had this knowing about that character. He was so generous onstage, and there was so much of him in that character.”

“It was always such a privilege to bear the torch of Jonathan’s [Larson] legacy,” he added. Brown carried that into every show.

After RENT, Brown went on to play Mufasa in The Lion King. In 2000, he took over for Billy Porter as John in the Broadway cast of Miss Saigon. But he never stayed away from his family for long—and they never stayed far away from him.

After several years on Broadway, Brown returned to New Haven for a short time, then moved out to Maryland 13 years ago. Before he left the city, Staton remembered bringing him in to work with her students at the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA) on Audubon Street, where she was teaching. By then, the two had grown very close, including a period during which Brown lived with her.

When he walked into the school and began to sing with his mother and siblings Janet and John, “those kids were sitting there with their jaws open,” she remembered. Staton later “begged him” to return from Maryland for performances of Black Nativity, which she directed for four years starting in 2013. He always did, reprising the role of the Angel Gabriel with cast members from his family, members of the Monk family, and the historic Vernon Jones singers.

When he performed, there wasn’t a dry eye in the room.

“He took a voice with him I don’t think I’ll ever see again,” Staton said. She last saw him a few years ago, when she was visiting Maryland.

In Maryland, Brown became the vocal music director for all five branches of Zion Church and a founding member of Restored Vocal Band, which had plans to visit New Haven this year. Each week, he designed the music program that welcomed Zion’s 10,000 parishioners and kept them coming back. In the weeks before his death, he had just finished two major projects including “A Miracle On Z Street,” a church-wide Christmas extravaganza held outdoors at Six Flags America.

Keith Battle, founder and senior pastor at the church, remembered Brown for his honesty and ability to keep friends accountable. He saw Brown as personifying Proverbs 27:6: “Faithful are the wounds of a friend.” At a homegoing service last month, he praised Brown for the kind of gentle, sometimes side-splittingly funny and sometimes wounding frankness with which he lived his life.

“He was always gonna tell you the truth,” he said. “He was always gonna be up front with you. And that’s what Charles would do … he showed up as a friend. Even when he knew your flaws or your family's flaws, it didn’t change his love or support for you one iota. He was a great friend.”

It was at Zion that Brown reconnected with Caldwell in 2018, after she had gotten married and moved to Maryland. From where she was sitting at the back of the church during services a few years ago, she couldn’t see Brown. But she could hear him. She started to jump up and down, trying to get a glimpse of the friend she loved so much. After the service, she tracked down a friend of his who got him on the phone.

When Brown found out that she was there after the service—she remembered him screaming her name joyously into the phone—he turned his car around and headed right back to the church. The two embraced and sat in the lobby catching up. The last time she saw him was during one of Gibson Brown’s visits to Maryland.

“He was whole,” she said. “He was whole. There were things that were missing when he was younger, and he filled those beautifully.”

“Serving Something Bigger Than Himself”

Brown was that kind of friend—an uncle, godfather, and father figure—to dozens of people he met in Maryland, and to New Haven friends with whom he stayed in touch. Years ago, he became an adoptive father to William Charles Brown, a son who now lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. At a memorial service at Zion last month, Restored member Jeffrey Hill remembered Brown as not only a friend and spiritual guide, but a loving confidant who showed up in his moments of greatest need.

When Hill’s father died a few years ago, Brown was the first person he thought to call. When Brown walked in, Hill was lying on the floor beside his father’s body. Brown laid down with him. He later became the beloved godfather to Hill’s six-year-old son William, whom he referred to as “Uncle Charles.” When the two were together—whether in song or in fellowship, or both at the same time—they were unstoppable. Members of Restored referred to Brown as "fire," because “he could just set the stage ablaze."

"Every time he touched the mic, he was blessin' lives," Hill said. “I know the same God that Charles worshiped is the same God that Charles saw when he opened his eyes Friday morning ... If we continue to live the life that Charles lived, if we continue to serve the God that Charles served, if we continue to do and act and treat people the way that Charles acted and treated people—we gon’ see him again.”

In the wake of his death, Gibson Brown said she has heard from dozens of people her son touched. One of Brown’s fellow choir members at Zion Church told her that he had shown up at the hospital when her own sister was dying, and she couldn’t get there fast enough. Josh Davies, speaking at his Maryland homegoing, told a story of how Brown had set the phone down after a conversation, and started singing. He didn’t realize that his colleague was still on the other line. Davies listened to him sing for three minutes, stunned and delighted.

“He was serving something bigger than himself,” he said.

Brown was buried at Evergreen Cemetery last month, after services at both Zion Church and at St. Matthews Free Will Baptist Church on Dixwell Avenue.

“He was phenomenal,” she said. “We need to be careful how we handle what God loans us. Because one day, He’s gonna come back to get it. And I have to remember that He only loaned Chuck to me. And so when He was ready, He came back and got it.”