Bridgeport | LGBTQ | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | City Lights Gallery

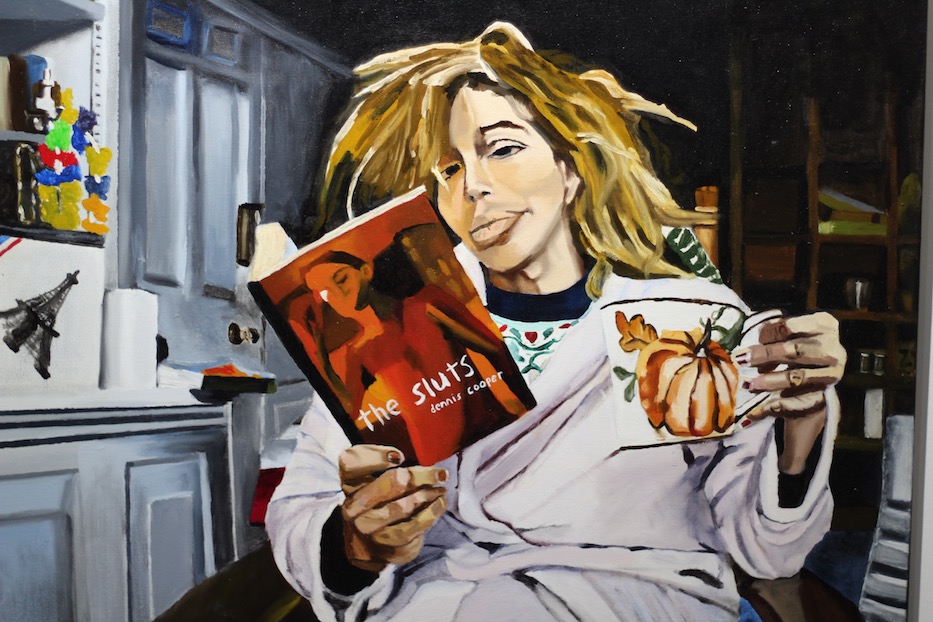

| Kevin Cox, "Daisy In Real Life" installed at City Lights Gallery. |

Daisy won’t look at the camera because she has better things to do. Between two fingers on her right hand, she tightens her grip on Dennis Cooper’s The Sluts, its orange-red cover almost enough to distract from her face. Almost. Her lips push together and relax with the words. A bathrobe hangs, belted, over her frame. In her left hand, a huge mug beckons with a pumpkin blooming across the side.

But who is Daisy? Why are we supposed to care so much about her?

Kevin Cox’s “Daisy In Real Life” is one of over 100 pieces now on view at City Lights Gallery as part of SAMESEX 2019, a group show of over 30 LGBTQIA+ artists who have come together for Bridgeport Pride celebrations. After opening July 18 as part of the ninth annual Bridgeport Pride and SAMESEX Variety Show, the exhibition runs through Aug. 30.

An artists’ talk is scheduled for Saturday July 27 at 2:30 p.m.at the gallery. Directions and more information are available here.

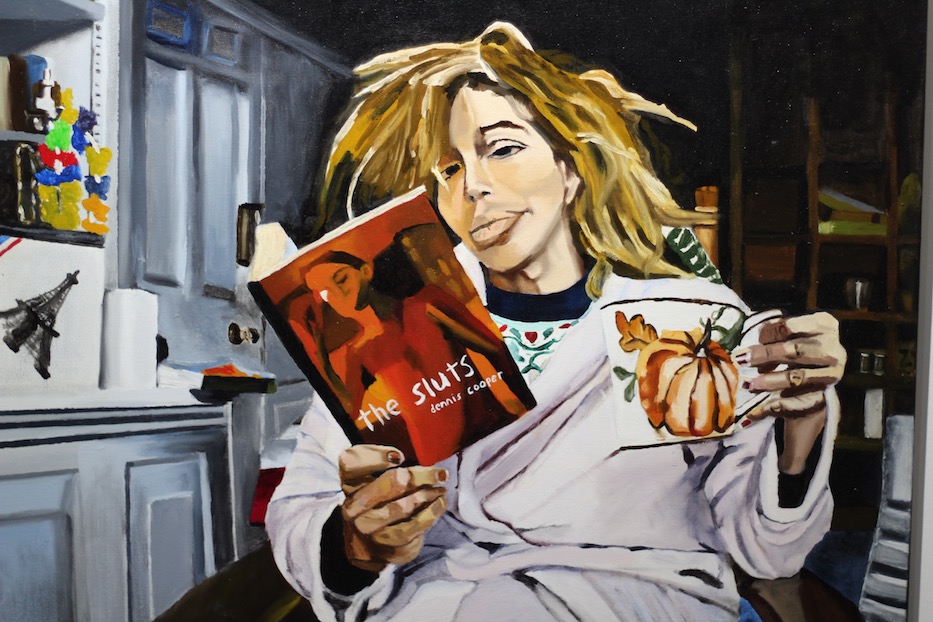

| Two of the photographs from Cassandra Mendoza's Trust Your Struggle series. |

SAMESEX pulls viewers in from the moment they enter the gallery, asking them to take a closer look at what they understand as LGBTQ+ art. On a far wall, Cassandra Mendoza’s Trust Your Struggle series looks out at the viewer, inviting them to come closer. In a photograph at the bottom right corner, the subject looks the viewer head on, eyes sliding just slightly to the right without ever drifting away. It's not a pugnacious look so much as a question, like hey, are you going to ask my name? Or maybe hey, what are you doing in my dressing room?

In another, the same face has shifted, lips somewhere between a smile and pout. Eyes travel downward, to a corner of the room we can't see. Hands rake through hair. A tattoo snakes across the collarbone with the simple direction: Trust the struggle. Viewers are left to figure out exactly what that means for the subject, and for them.

That closer look—often head on—defines many of the works in the exhibition. Not far from Mendoza’s work, Luis Lopez’ Midnight At Trevi Lounge series takes over a section of white wall with bright acrylic on board compositions, each depicting Lopez’ friends (sometimes in multiple shots and poses) during their time at Lopez’ local gay bar. They pull the viewer in with an immediate familiarity: we may not know these men but we want to, with their broad grins, laughing cheekbones and close-up, piercing eyes.

| From Luis Lopez’ Midnight At Trevi Lounge series. |

“Using portraits to bring you up close and personal with some of the people you may find there on a regular night, the intention is to trip the over-sexualized nature of bodies in order to get a more intimate conversation with these individuals, something that can be primal and sexy in its own light,” reads an accompanying label.

That’s true of Cox’s work too, hung salon-style on a nearby wall. Images from his This Is Me series are particularly intriguing: the artist has found subjects through their photographs on social media, and reimagined those same people in the real world. Gone is the schmaltzy pose and self-confidence of the selfie, replaced with how they might look if stumbled upon unexpectedly.

In “Daisy In Real Life,” that juxtaposition is front and center, placing the subject in a frumpy bathrobe as she's trying to get some reading done. Here is someone who has spent time on their appearance: nails painted, lips full, hair streaked with blonde. But the curtain has been pulled back: Daisy just wants to read her book and drink her coffee too. She’s normal, like viewers are. And she’s not actually always ready for the camera.

In another room of the gallery, Sarah Stinson-Hurwitz’s work (pictured above) beckons to the viewer with a spray or bright color, then takes their breath away with “Trying To Remember The Ones I Never Knew: A Memorial To The Lives Lost At Pulse.”

Commemorating several of the victims of the 2016 shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Flo., Stinson-Hurwitz has chosen simple materials for elegiac pieces: acrylic paint and canvas fabric, frayed at the edges like a funeral shroud. Her subjects—all of whom are so young that it is hard to imagine them not full of life—look out at the viewer. Eyes flutter wide. Lips part as if to start a sentence that viewers won’t get to hear the end of.

“This work is my general effort to place attentions on remembrance, love and support of those who lost their lives at Pulse,” she writes in an accompanying label. “Our community was attacked, and we need to continue to commemorate those who were lost.”

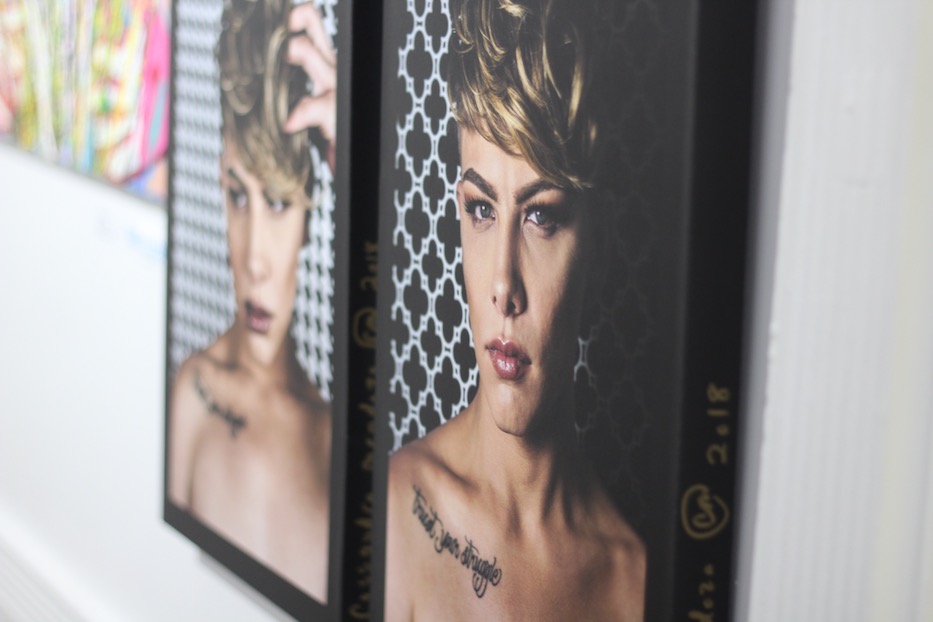

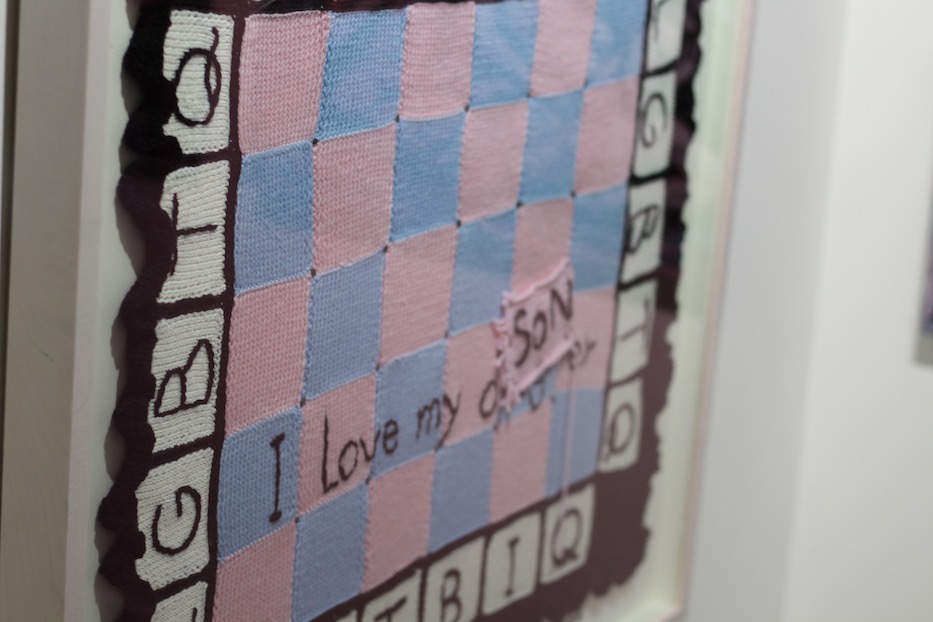

| Nancy Moore. |

Other images reference the history of craft and process, drawing from folk arts to stark, startlingly clean portraiture. On the far end of the gallery, Nancy Moore is cheeky and smart in her mixed media “Blanket Statement,” a kind of crocheted homage to LGBTQ+ and particularly trans rights that is also a literal baby blanket.

In the center of a blue-and-pink checkerboard pattern, Moore has stitched the words “I love my daughter” in black, then added a pink strip over the word “daughter” to account for the word “son.” It’s intentionally messy: black thread from the word underneath still spills out, in a seeming reference to Moore’s own best efforts and occasional missteps. As if the acceptance was always there; it was just waiting for the right time to come in and mend the ills of the past.

Photographs both channel and play with portraiture, pose, color scale and framing. Across from Stinson-Hurwitz’s work, artist Margaret Kraus has placed three arresting photographs on metal, including a portrait of her sister Vivienne in profile against a painting at the Whitney Museum of Art, as a rainbow of color arcs and explodes over her head.

| Pieces by Margaret Kraus. |

Artist Andrew Graham has taken a different approach in four calculated, carefully framed shots that play with the limits of human form and movement. In one, titled simply “The Dancer,” a man presses his head to one raised leg, knee bent and toe pointed beneath it. His back has become a thing of immense, living beauty: muscles ripple and arc, his spine rises up like a tide pulled toward the moon.

The gentle curve of it all is not sexualized, even as it dips into his smooth buttocks. Instead, it’s a body that doubles as a study in light and shadow. So too his “Ensnared,” as a model looks out at the viewer from what appears to be a fishing net. There’s no cause for alarm here, he seems to assure them: his arms are pulled calmly around his legs, feet flat on the ground.

“We live in a society where we are often discouraged from being ‘naked’ to the world around us,” the artist writes in his statement.

| Andrew Graham Photographs. |

“But is that really who we are? What about our deeper selves – our ‘naked’ selves – that which makes us weep with abandon, laugh out loud, or that which gives us reason to rise each morning? What are our passions? What is it that makes us vulnerable? Can we share these parts of us?”

Like the photographs, SAMESEX bares all without ever seeming overwrought. Its greatest strength may be its role as a group show, where voices emerge in a jumble, and get behind a narrative of acceptance and visibility. Each offers something slightly different: a reframed viewpoint, a personal anecdote put to paper or canvas, a vignette or five that dive into love, sex, joy, and beauty. As they whisper and chatter with each other and with viewers from the walls, City Lights seems to speak with a united voice too.

Welcome, the gallery says from every single vantage point. We’re so glad you’re here. Come exactly as you are.

SAMESEX 2019 runs through August 30 at City Lights Gallery, 265 Golden Hill St., Bridgeport. Visit them online for hours, directions or more information.