Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | Refugees | Sanctuary Kitchen | Arts & Culture | Culinary Arts | Arts & Anti-racism

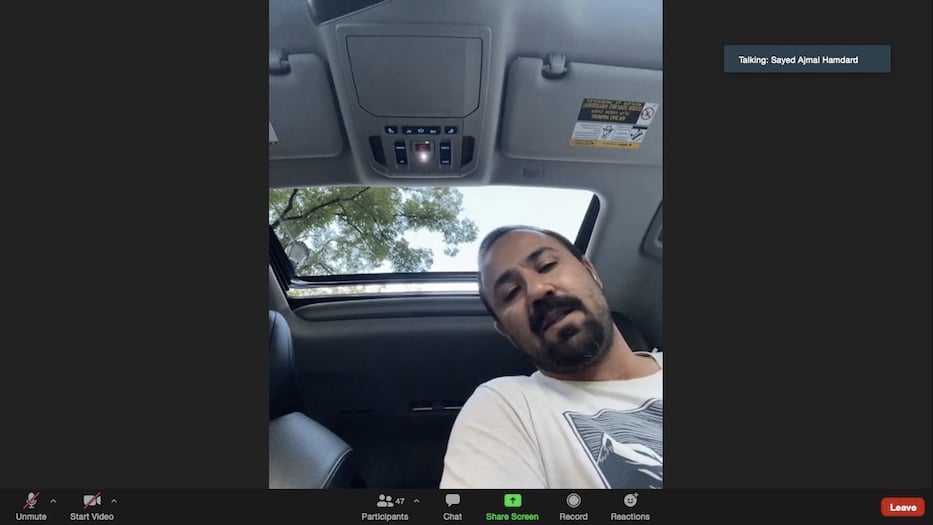

Chef Homa Friday night. Screenshots via Zoom.

In the aush reshta, yellow from fenugreek and thick with red beans, flat noodles and spiced yogurt, there is a story of a brother waiting for news at the Kabul airport. The sabzi, gem-colored spinach sautéed with kidney beans, holds the history of in-laws that have gone into hiding. The Korma Lawand, a stew of chicken with spices, onions and ground nuts, is now the taste of an evolving diaspora.

Those dishes gave New Haveners a window into Afghanistan Friday night, as refugee chefs, Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) holders, and representatives from Sanctuary Kitchen at CitySeed and Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) held an emotional and at times gut-wrenching conversation on the collapse of the Afghan government and emergency evacuation efforts from Kabul this week. Close to 50 people attended virtually on Zoom.

Last week, Sanctuary Kitchen donated a portion of its proceeds to IRIS, which it plans to again this coming Friday (order here). In just over an hour, the discussion became a testament to both the devastation of the United States’ longest war and the ability of food—even eaten at a large virtual table—to foster and catalyze understanding across borders.

Syrian hummus, Afghan spinach sabzi, and Syrian Salata Jarjeel were some of the items on the menu Friday. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Speakers included Sanctuary Kitchen chef Homa Assadi, who hails from Afghanistan’s Ghazni province; Sayed Ajmal Hamdard, who served as an interpreter with U.S. forces in Afghanistan; developer Farid Samadi, who worked for Chemonics and USAID in Afghanistan; IRIS Community Engagement Director Ann O’Brien; and Sanctuary Kitchen Program Director Quynh Tran, herself the child of Vietnamese refugees. Samadi's wife, Hosna Samadi, interpreted from Farsi for much of the event.

“Please help Afghanistan people,” said Hamdard, joining the conversation from his car. “We call out to the world, please help our people.”

The discussion came just a day after an attack outside Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport left over 90 Afghans and 13 U.S. soldiers dead and hundreds more wounded. Currently, thousands of Afghans who assisted U.S. troops are trapped in the country, desperate for SIV approval and evacuation. Earlier this month, the International Rescue Committee reported that there are over 18,000 “applicants in the pipeline” for SIV status. Meanwhile, U.S. President Joe Biden has maintained an August 31 deadline to be fully out of the country.

As dozens of one-inch boxes filled the screen, Assadi described dishes that she and fellow Afghan Sanctuary Kitchen Chef Maleka have been working to cook this week at the organization’s home on Legion Avenue. This week, she blended chicken, nuts, onions and spices and channeled a homeland where many of her relatives are now in hiding. She kneaded discs of naan, soft from milk in the dough, and baked in stories with nigella and sesame seeds on top.

In New Haven, some attendees opened their containers of aush reshta and creamy sabzi, studded with kidney beans and bits of onion, and plated them as the program began. Speaking in Farsi, Assadi wove a through line from the food back own life in Afghanistan, a culinary tradition that began with her father’s tutelage in the Jaghori district decades ago. In 2015, she came to the U.S. with her husband and three kids. Months later, she connected with Sanctuary Kitchen through ESL teacher Donna Golden, a member of IRIS’ cultural companion program.

Currently, members of her family are in the country’s northern Baghlan Province, which Taliban forces took control of earlier this month. Her brother headed to Kabul last week, she said, and had been at the airport for about three days as of Friday night. At the time that she spoke, it was about three in the morning in Kabul.

“He doesn’t know where [to go], but he just wants to get out of Afghanistan,” she said.

Her words tumbled out in Farsi, sometimes halting only when Tran and Samadi asked for a chance to catch up. She spoke of her concern for her in-laws, who are elderly and isolated. Her husband’s brother lives in Indonesia, which means no one is there to take care of his parents.

She said that the rapid collapse of the government reminds her of the 1990s, and the years leading up to the 1996 Taliban takeover of Kabul. Six years ago, when she left Afghanistan, she feared that this would one day happen. Now, it has. She pointed to the Taliban’s persecution of women, Afghans who worked with U.S. troops, and members of the country’s religious minorities.

For months—years, even—members of Afghanistan’s Hazara population have been increasingly at risk, including nine Hazara men murdered by the Taliban in Ghazni province earlier this summer. Hazaras practice the Shia branch of Islam, putting them at risk in a majority-Sunni country now ruled by a militant Sunni group.

“Everyone knows about the Afghanistan situation,” she said in Farsi, Samadi reminding her to stop for translation every few sentences. “It’s very bad … Everyone is worried about their family. Everyone is so worried, and they are living in a very bad situation right now.”

Both Hamdard and Farid Samadi spoke about their own experience in Afghanistan and now in Connecticut, urging attendees to call their representatives and support resettlement efforts as thousands of Afghans who helped U.S. troops remain trapped. On Sunday, emergency airlifts out of the country all but ended following a U.S. drone strike in Kabul.

Hamdard, who worked with the U.S. Army in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2013, jumped into the conversation. During his time in Afghanistan, he was a translator on a base in the Logar province, which sits in the east of the country. In 2016, he came to New Haven with his wife and two children on an SIV. Many of his colleagues and family members are still in Afghanistan, desperate for a way out.

He said he is most worried about family members, including a brother who is in the country, and those who worked alongside U.S. military forces, in police and intelligence, and for the Afghan government. From friends and former colleagues, he has received firsthand reports of the Taliban going door to door, checking for and often confiscating documents that show collaboration with U.S. forces.

Of the interpreters he worked closely with, one was able to get to Dubai last week. He said that another two are in Kabul, trying to leave the country. “Yesterday thank God, two of them were far from the blast,” he said, adding that they text each other as often as they are able to.

“Whatever you see in the news that the Taliban say, it is not true,” he said. “They are getting letters, trying to kidnap people one by one. Whether they are killing [them] or whatever they do, it’s unbelievable.”

As he spoke, the grey roof of his car stretched over his head. A low-hanging New Haven sky peeked out from beyond a closed window. He described friends who were left scrambling in Logar province, and others who are in Kabul as the likelihood of emergency evacuation fades. He does not know if they will survive this chapter of Afghan history.

“And we know. The Taliban, when they take over the government, they always do whatever they like to do,” he continued. “We are right now looking to find a way to help our families. Because we know, right now, the Taliban, they will never leave those people alone.”

Samadi, who started working with U.S. forces as a developer in 2008, said he is “extremely concerned” about the August 31 deadline that Biden has set. In 2016, he received his SIV, and came to the country with Hosna and their two children that year. Because he was “extremely passionate” about his work, particularly gender equity efforts with USAID, he then returned to Afghanistan to continue working. Several months ago, he returned to the U.S. He said that the Taliban has made it likely that he will not return again for some time.

“The situation in Kabul and in Afghanistan is horrifying ,” he said. “Everyone is hopeless. People are living in fear. Those people who attach themselves to airplanes or hide themselves in a part of an airplane … that was because of the fear. In any case, they will be tortured, they will be killed. That is painful.”

He knows of 50 colleagues who have applied for the same Special Immigrant Visa status and are still awaiting approval. So far, he said, only one staff member has been able to get to Qatar with his mother. He has watched as Afghans, desperate to flee, die trying to grab onto airplanes as they are taking off.

He fears that on August 31—Tuesday of this week—they will also be completely abandoned after assisting the U.S. in a war that stretched over two decades and involved tens and thousands of his colleagues, friends, family members and fellow Afghan citizens. He worries that journalists will also stop covering the country, allowing the Taliban takeover to fade from media memory within a week.

“What I’m trying to say is that August 31 will not be the end of the game,” he said. “We need to organize. We need to advocate. We need to go to the politicians … to make sure that they are not forgotten.”

“I hope the United States will pay attention to the priorities list and get out those people who worked for them,” he added.

Golden, a founding member of Sanctuary Kitchen who is still with the group, asked Samadi if he could shed light on the evolving situation for women and girls in the country. Among stories of female soccer players, girls’ robotics teams and pioneering women journalists who made it out, there have been harrowing accounts of women beaten, kidnapped, and turned away from their workplaces and classrooms by the Taliban.

He said he does not yet know what the future will hold for them. Currently, the Taliban has said that girls will be able to return to the classroom—a promise that he thinks will last only “if the world recognizes them as a legitimate state.” He recalled being a university student in 1996, and watching as women were thrown out of and then barred from their workplaces.

“If the international community does not recognize them, human rights, minority rights, education, free media” are all endangered, he said. “At least publicly, it seems that they are open to discussion. Let’s see.”

In part, Tran said, the event spoke to the core of Sanctuary Kitchen’s mission. Members of CitySeed founded the organization in 2017, months after President Donald Trump sought to stoke fear through a restrictive ban on refugees from majority-Muslim countries. Four years and one presidential administration later, Sanctuary Kitchen has grown to over a dozen refugee chefs from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, Mauritius, and Democratic Republic of Congo.

“We were founded based on this idea that sharing a meal and sharing personal stories fosters an environment where people can really come together and develop a sense of welcoming and acceptance,” Tran said. “Because it quite literally brings people to the table.”

From Afghanistan To Aid In New Haven

The dinner conversation also gave New Haveners a glimpse into the rapidly changing situation on the ground, and a look at how they can help from the U.S. Representing IRIS, O’Brien said that staff members have been working around the clock as Afghan families arrive in unprecedented numbers. The organization has been on 24-hour notice since August 4, when the U.S. State Department notified them that families could be arriving at any time.

Since August 6—when they were notified that two families were on their way—IRIS has helped resettle five families, for a total of 32 people. Another is expected this week. After August 31, O’Brien said IRIS then expects “large numbers in a short period of time,” including those who may have to work with legal help to ensure refugee status in the U.S. She does not yet know how many arrivals that means, she said—nor does anyone at IRIS.

She did say that the U.S. State Department has notified IRIS that it needs to say how many families it can take in the coming months. Many are SIV holders; others are coming with a government program called Humanitarian Parole.

So far, families have arrived so quickly that IRIS has housed them temporarily in hotels. In a rental market that is more expensive than it was 16 months ago, the organization is struggling to find safe and affordable housing for refugee families, the upper end of which is $1,500 for a three-bedroom apartment. She asked those on the call to be in touch with housing leads, for which IRIS is constantly searching.

“One of the things that we are grappling with is that the housing market is incredibly tight,” she said. “There are very few apartments available, and the ones that are available are more expensive than pre-pandemic by a couple hundred dollars a month, which could make or break a refugee family’s budget.”

The situation is also complicated by IRIS’ attempt to stay in touch with roughly 100 clients who returned to the country to see family earlier this summer, when the government seemed stable enough to do so. In early August, IRIS learned that clients would have to submit a federal document called a Citizen Repatriation Form to get back into the U.S.

“We knew that our clients would not know what that form was, because we had never even known it existed,” O'Brien said.

Immediately, the organization started working with clients to fill it out across the distance. O’Brien said that all staff members, including ESL teachers, have pivoted to assisting with the repatriation form process and staying in contact with the families.

Fighting back tears, she said that 50 clients are in transit back to the U.S., while another 50 are currently in Afghanistan, some outside of Kabul, or have crossed into other countries. Many have asked the organization if they should risk the trip to Kabul or try to flee elsewhere, a decision that O’Brien called incredibly difficult as news changes not by the day or the hour, but by the minute.

“Everything that you’re seeing in the news is absolutely accurate,” she said, her voice catching as she spoke. “Whatever the Taliban is saying through their public spokesperson is not how they are acting on the ground. They are going door to door and they are asking for documents and they are taking them away. Our folks are either staying in hiding or staying with military that they have stayed with before.”

She added that the organization needs help as it adjusts to a new normal for refugee resettlement. On its website, IRIS asks its supporters to call their representatives, connect with regional resettlement groups and agencies, collect school supplies, backpacks, and winter clothes and donate to the organization if they are able to.

They are in particular need of winter coats, O’Brien said. In addition, the organization will be opening a satellite office in Hartford, where many refugee families have been resettled, this fall.

Sanctuary Kitchen will be donating a portion of its proceeds to IRIS this week. Order here or donate directly to IRIS here.