Dr. Thomas RaShad Easley had the Whitneyville Cultural Commons at a hush. He launched into “All Eyes on We,” a song he wrote in 2013 with middle school students in North Carolina, during an outdoor education program in a southern forest.

Dr. Thomas RaShad Easley had the Whitneyville Cultural Commons at a hush. He launched into “All Eyes on We,” a song he wrote in 2013 with middle school students in North Carolina, during an outdoor education program in a southern forest.

Here is my minority report/About what’s going on with the poor.

No clean water, got liquor stores…

No banks, good housing can’t afford…

I don’t own a gun, but I am at war,

Praying ‘bout who coming after the 44th…

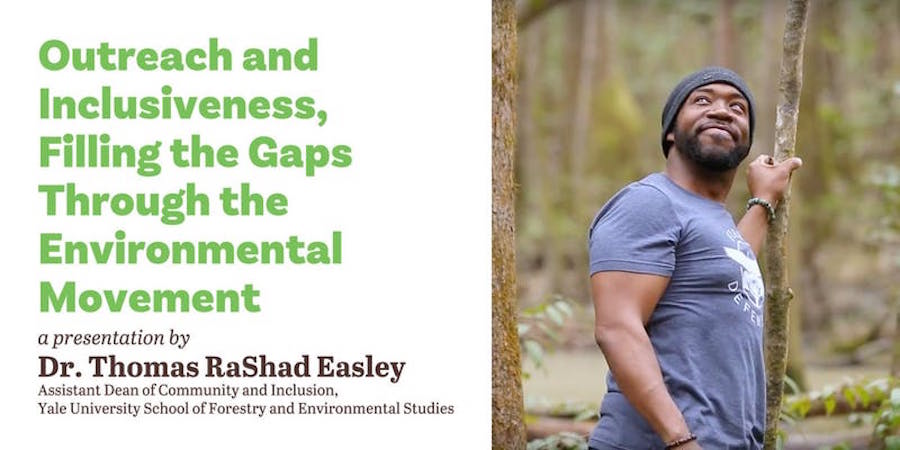

Easley is a professor, forester, diversity facilitator, minister, hip-hop artist, business owner, and community organizer who moved to New Haven from North Carolina last year. Currently, he serves as the Assistant Dean for Community and Inclusion at Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies (FES). Friday night, over 75 people gathered at the Whitneyville Cultural Commons in Hamden to hear him speak on “Outreach, Inclusiveness and Filling the Gaps Through the Environmental Movement.”

Easley’s talk was the public portion of the annual meeting for the Greater New Haven Green Fund, an organization that provides grants to community groups working to promote sustainability, advocate for equity, and fight pollution. Green Pond President Lynn Bonnet said that the group is “always trying to improve our outreach into the community.”

And in that spirit, Easley fit right in. Activism is at the core of who he is. In the 1960s, Easley’s maternal uncle was the first field lieutenant appointed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His family was, and continues to be, rooted deeply in the Civil Rights movement. Easley said that the environment is important to him because he depends on it—for water, food, oxygen, health, even his career.

“I feel like I owe the environment something,” he said in a phone conversation after the event. “I feel not just compelled, but honored to take care of it and try to give something back … There are ways that we can utilize and take from the environment and give back more than what we use at the same time.”

As he took the mic Friday, Easley said his ultimate goal for the evening was “to make a community connection and let people know we are available to help”—to define environmental justice and describe a guiding philosophy for engaging communities. In his world, that means the intersection and interplay of environment, economics, politics, racism and classism. To help everyone understand what that looks like in real life, Easley told the audience about the genesis of the environmental justice movement.

“Anyone know in what state the environmental justice movement had its origin?” he asked, turning the audience into his students for a brief moment.

One audience member shouted out “North Carolina!” Easley, who spent over a decade at North Carolina State University, broke out in a broad smile and said, “I love that state!”

But the story he told next of Afton, North Carolina sharpened the focus in the room.

In 1982, state and local officials in North Carolina were faced with cleaning up the unlawful private dumping of oil on state roads. The oil contained extremely toxic polychlorinated biphenyls, (PCBs) and officials had decided to build a landfill near Afton to dump the environmental waste.

For six weeks, 500 people protested the landfill. Easley’s slides included a striking photograph of citizens lying in the street to bar the way to trucks. He told the story of an 8-year old child determined to protest and risk arrest alongside her mother.

What stood out the most for Easley was how vulnerable the population of this community was. Afton was (and still is) home to single mothers, seniors, and a sizable Black population, many members of which were living in poverty. The town lacked basic municipal services like water and sewer connections. The citizens had to fight an uphill battle, which Easley described as a hallmark of environmental justice.

“The burden of proof is always on the victim,” he said. “The victims who are suffering pain for it, have to prove it.”

Easley’s philosophy is that the best way to engage with and help a community is to first ask community members what help they need. He elaborated during the question and answer segment, when someone asked how to have a global impact in the fight for environmental justice.

“If you want to save the world, start with your corner,” Easley said. tHe suggested that the effort starts at the grassroots—that “we need to get input from people there first.”

He said that it’s problematic when people go abroad to help others, thinking primarily of their own experience and not taking into account the needs and preferences of the very people they wish to help. “That’s walking in the wrong kind of privilege,” he said.

He also extended the conversation to how those grassroots efforts can include youth. Easley came alive telling stories about working with middle schoolers. In 2014, he and a couple of his colleagues developed the “Neighborhood Ecology Course” with youth in Raleigh.

The year before, he had been in a forest with North Carolina youth, writing hip-hop about the contrast they saw between the neighborhood they came from and the natural surroundings they were experiencing. Inspired, Easley and his colleagues worked closely with a Raleigh community center to expand this one-time experience into an annual summer program. Their approach was to get the kids talking about their own lives and then help them connect that to environmental science.

“We started with ‘Do you know where your water comes from? Do you know where your food comes from? Do you know where your trees comes from?’” Easley recalled. “We told them, ‘We want to show you where this stuff comes from and we’re going to do it in your neighborhood. And we’ll also go to the mountains and the beach and we’re going to pay you.”

Students loved the program so much they came back year after year and then took on leadership roles as high-schoolers.

Easley said that above all he wanted “to make a community connection and let people know we are available to help.” Audience members eager to collaborate with Easley and FES made that hope a reality.

The line for a few face-to-face moments with Easley wound around the room. Even more attendees were interested in talking to each other, introducing themselves and swapping knowledge about community programs, or updating a friend on the progress of their garden.

“Thank you for being awesome,” one audience member said.

To listen to "All Eyes On We," click on the audio below.