Books | Education & Youth | Environment | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Public Health | COVID-19

Lucy Gellman Photo.

Sippy The Straw has drifted to the middle of the ocean, where he floats among two sea turtles in the gem-colored depths. From where he bobs back and forth, he can see their wide eyes and eager, wrinkled jaws. But he’s getting worried: it’s snack time, and the turtles are about to eat jellyfish that are not jellyfish at all. They’re plastic bags, which can cause permanent internal damage.

He opens his mouth to warn them, but he’s underwater—so only bubbles come out.

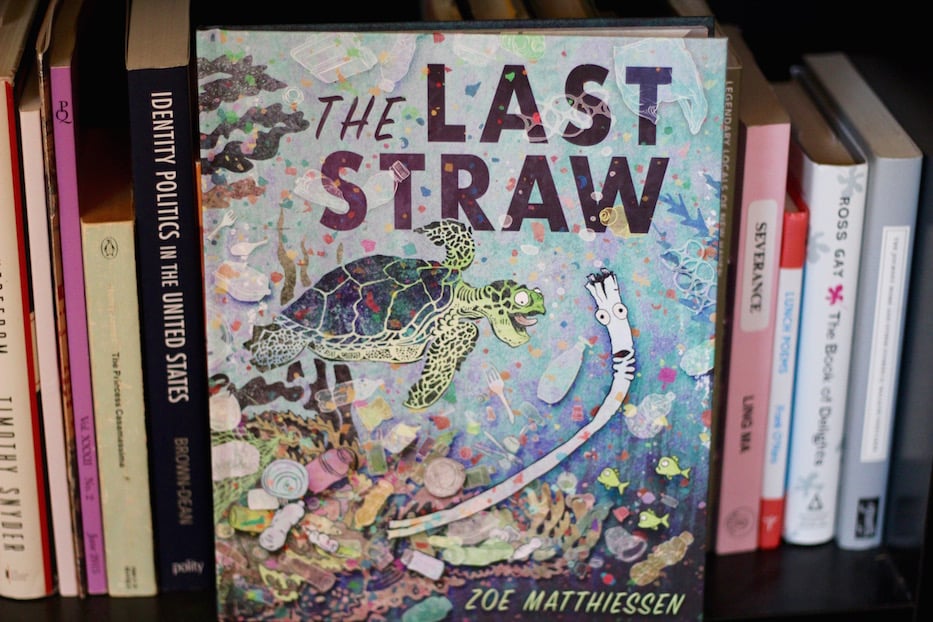

Sippy is the brainchild of illustrator Zoe Matthiessen, a local artist and environmentalist who may be best known for her cartoon series Ecocide in the New Haven Independent and more recently The Nation. This year, she wrote and illustrated her first children’s book, The Last Straw, to teach young people about the havoc that plastic waste is wreaking on the environment. The publication—which is printed on recycled paper—is available through North Atlantic Books.

“I’m Sippy, I guess,” she said in a recent Zoom call from her home in Wooster Square. “I’m the one observing the horrible situation with plastics in the environment, and its impact on everything out there. It’s bad out there. The book is based on research and photo evidence. It’s not over the top. And I just wanted to find a way to present it to a wider audience. A younger audience.”

.jpg?width=933&name=01-OPENER%20(1).jpg)

Images Courtesy of Zoe Matthiessen.

The Last Straw follows a discarded plastic straw named Sippy as he travels through the world, where he is picked up, dropped, and ingested by animals who mistake him for a part of their natural habitat. At the beginning of the book, he is snatched up in a cardinal’s yellow beak, the bird’s eyes beady as it inspects Sippy and takes flight. The straw is soon distraught: the bird’s nest is made of plastic cutlery, bits of plastic toys, bubble wrap, and bottlecaps. The bird explains that it doesn’t want to make a plastic nest—but it must work with what it has.

“I build with what I find out here!” the bird chirps in clean, rhyming prose. “These days I can’t be picky!”

The story—told in bright hues and disarming pastels—hovers between a cautionary tale and a solid punch to the gut. Sippy tries to warn birds, fish and furry friends (and by extension, his readers) of the dangers that plastic poses to life on earth, from owls entangled in plastic string to shell-bereft hermit crabs that hide inside washed up toothpaste caps. Everywhere he goes, he sees plastic, realizing that it has taken over land, sea, and sky. For young and adult readers alike, it’s a sharp reminder of one giant man-made crisis in the midst of another.

Images Courtesy of Zoe Matthiessen.

In one scene, Sippy happens upon a young owl who is alone in the woods, tangled in the strings of a crinkled, smiley-faced balloon that stares back tauntingly at him. In another, he meets a raccoon who is stuck in the plastic rings of a six pack container and can't get out. There’s a seahorse who swims through curtains of trash looking for fellow fish, and an ocean floor piled with plastic detritus where there should be coral, sand, and microscopic sea life.

Toward the end of the book, a huge blue and purple whale swims through the ocean, her mouth open wide on the hunt for dinner. But the sea is full of plastic, rather than the plankton, krill and squid she should be eating. The whale chomps on the plastic, unable to tell the difference until it is inside her. Sippy, who is swallowed in the process, pleads to be let out. When he is expelled unexpectedly from her blow hole, he vows to share his warning with the world.

For Matthiessen, who went through several storyboards for the book, that ending ultimately felt right for Sippy’s non-recyclable fate. She and the publisher decided that it was also the most realistic outcome—Sippy may dream of being recycled, but that isn’t in the cards for him. Matthiessen kept that in mind as she hand drew each distinct piece of plastic that Sippy comes across in his journey.

.jpg?width=933&name=13_WHALE%20(1).jpg)

Images Courtesy of Zoe Matthiessen.

“I was like, am I supposed to end with him lying in a landfill or going up in smoke?” she remembered. “There’s really no happy ending in this world for a plastic straw. So we talked about it, and we decided that he never dies. He just keeps floating around and telling his tale and that is his purpose. To tell his story. He’s immortal. He’s plastic. He’s always going to be with us—but at least he can educate kids and adults along the way.”

She landed the book deal last year, after a friend connected her with a colleague at North Atlantic Books and the publisher gave her two days to prepare a pitch. The story was easy, she said: Matthiessen looked to the illustrations she’d churned out for Ecocide, which began with a duck trapped by a plastic trail mix bag over its head. She decided to build the images into a plot meant for both young readers and their parents. The cartoon has been running for years, which gave her plenty to work with.

She called herself “totally indebted to” New Haven Independent Editor Paul Bass, who first spotted her illustrations in a small window on Broadway Avenue and York Street four years ago, when he was waiting for the bus home. At the time, she was living there and using a street-facing window of her apartment building as a sort of rotating gallery space.

Images Courtesy of Zoe Matthiessen.

Bass saw the images and offered her a weekly spot for Ecocide. She sometimes stayed up all night to finish the cartoons in time for his 7 a.m. deadline. During those years, she also sent viewers on scavenger hunts, where she left drawings hidden in East Rock Park with clues to find them.

“I think that graphic art often presents an issue in a way that makes you feel the impact of the issue, rather than have it be a dry set of words that you can see on the page,” Bass said in a phone call Wednesday morning. “An image can sear itself into your mind.”

He added that there’s something succinct and disturbing about seeing an animal caught in an unintended plastic trap. A news article or opinion piece, however well-written, is not going to pack the same punch. He pointed to work by Art Spiegelman and Sonny Liew that have left him equally thoughtful about events in political and global history.

“With environmental issues, you can easily descend into the fog of polysyllables,” he said. “She gets you to care. Graphic art gets you to care … the power of a great cartoon cannot be matched by any number of op-ed words. And it's a reason that art is an essential part of politics, and politics is an essential part of art.”

Like the series, each illustration is inspired by real-life news coverage and data collection that shows a global epidemic of plastic pollution. The sea turtles, for instance, are based on the 52 percent of turtles worldwide that have now eaten plastic. It’s a number that becomes more horrifying when paired with the 90 percent of seabirds that are also facing plastic waste in their food.

For those animals, plastic causes internal blockages that lead to exploded stomachs and irreversible intestinal damage. That’s also true for whales that have been found across the globe with over 80 pounds of plastic in their bellies.

Matthiessen during a recent conversation on Zoom. "I think people are really in denial about how bad it is," she said.

Matthiessen’s own environmentalism was born when she was a kid, growing up in Versailles, Kentucky. At 12 years old, she went vegan after thinking about how her warm hamburger had once been a living, breathing cow. In those years, “there was no tofu” in the American South, she remembered with a laugh. She made do with what she had, and then expanded her repertoire when she moved to New York and New Haven. She now makes vegan cheese in her spare time.

In New Haven, she’s nurtured her love of the natural world in the city’s parks. For years, she loved drawing trees in the woods around East Rock, where she would stay for hours before biking home. A decade or so ago, she heard the sound of something rustling and ripping that wouldn’t stop. It upended her afternoon.

“So I’m sketching this beautiful tree, listening to the birds, the fish are leaping, the bubbles are popping in the waterfall, and then I hear this,” she said, crumpling paper until it crackled and squeaked over Zoom. “And so I look up, and there’s this plastic bag hanging from a tree branch. I couldn’t get away from that. It made me so angry that it would be there.”

When she got home, she started Googling plastic pollution. There were images of animals choking on plastic and stuck inside plastic bags. She saw plastic tubing that caused ducks to starve when it got caught on their beaks. There were beaches covered in plastic and children swimming in and through floating mountains of waste. She made her first environmental cartoon, for which she now has a small and growing archive.

Matthiessen is quick to add that her advice is to both avoid plastic and “reuse, reuse, reuse” wherever possible. She seeks out refillable pens instead of single-use plastic ones. She washes and reuses Ziploc bags when they come into her possession. The netted bags that carry garlic and onions have become her soap containers. She buys most of her clothes at thrift stores to avoid new fabrics, which contain microplastics and synthetics made from fossil fuels. Her favorite shirt is a thrift store turtleneck that she’s had for over 10 years.

In the back of The Last Straw, there are also suggestions for easy ways to reduce plastic waste, such as carrying cutlery and keeping glass and metal containers on hand for leftovers. She said that she thinks of herself not as a children’s book author, but an artist who happened to put her message in a book for kids. She has started including eco-friendly coloring book pages when people buy a signed copy, inspired by a young reader who sent her a letter dedicated to reducing waste in his own life.

“I think people are really in denial about how bad it is,” she said. “Anytime you are faced with a piece of plastic, ask yourself if it is necessary or can it be avoided? There may not be a solution every time, but it is always good to get in the habit of asking: Do I need this?”

Find out more about The Last Straw here.