Downtown | Arts & Culture | Theater | Yale Rep Theatre

| Twelfth Night runs at the Yale Repertory Theatre through April 6. Joan Marcus Photos. |

Duke Orsino is floating in space as he dreams of Olivia. Behind him, a diamond pulses with neon light, casting blue and pink shadows on the stage. Before him, a screen comes to life in brilliant color, Olivia’s face fading in and out across it. Her likeness shimmers. His chest heaves; arms flutter out like wings. In the theater, house music builds into a wild, danceable heartbeat.

“If music be the food of love/if music be the food of love/if music be the food of love,” booms a woman’s voice, echoing words the duke has just spoken. Dancers bust out with their best moves, hips shaking in a blur of bright white and pink. Everyone is wearing virtual reality glasses. And for a moment, it’s not clear whether this is Illyria or Wakanda, or just the club. Or, perhaps, whether the difference matters at all.

So begins a boisterous, sublime, and unapologetically Black production of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, running now through April 6 at the Yale Repertory Theatre. Directed by Carl Cofield and told through an Afrofuturist lens, the work both turns Shakespearian conventions on their head and does nothing of the sort, driving home the Bard’s adaptability and potential for worldbuilding four centuries after his death.

That, and it puts the Rep back in representation. Tickets and more information are available here.

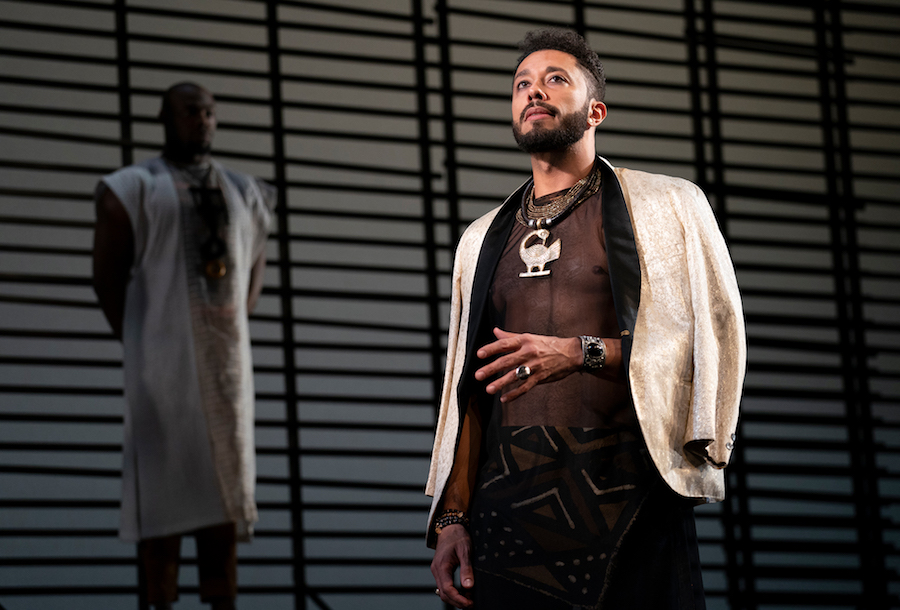

| William DeMeritt as Orsino in Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare, directed by Carl Cofield at the Yale Repertory Theatre, 2019. Joan Marcus Photo. |

Written at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Twelfth Night begins with siblings Viola (Moses Ingram) and Sebastian (Jakeem Powell) separated at sea, one washed ashore in the fantastical, fictional dukedom of Illyria while the other is rescued by benevolent sea captain Antonio (Manu Kumasi). Both, thinking the other has died, try to adapt: Viola fashions herself after her brother and becomes a gentlemanly aide to Orsino (William DeMeritt); Sebastian finds his way to Illyria, unaware that he has a doppelgänger who is actually his sister on the island.

Orsnio has love problems of his own, pining for the Lady Olivia (Tiffany Denise Hobbs) who is over him before it begins. Two love triangles, a lot of penis humor, and the inevitable complications of gender-bending ensue.

In Cofield’s hands, this Illyria is something to behold, with side-splitting humor but also the pursuit of Black love that is literally center stage. From the moment the play’s first words—”if music be the food of love, play on!”—escape from Orsino’s lips, it’s abundantly clear that the cast has been steeped in the verse, their understanding of the text making the story soar. Both lead characters and smaller roles like Maria (Ilia Isorelýs Paulino, who strikes a perfect balance between mischief and no nonsense) cue the audience into it, guides to an enthralling new-old land.

| Chivas Michael as Sir Toby, Erron Crawford as Feste, and Abubakr Ali as Sir Andrew Augecheek in Twelfth Night. Joan Marcus Photo. |

No dick joke gets beyond Sir Toby (Chivas Michael) or Feste (Erron Crawford), but it’s more than that. Cofield, with composer Frederick Kennedy, finds incredible music in the script—Feste lifts the play with a soaring and autotuned version of “O mistress mine” that channels Janelle Monae and Drexciya instead of a courtly afternoon.

There’s (blessedly) no lyre here, but a razor scooter that doubles as part air guitar, part-remote. Around him, characters have fun with the text: Abubakr Ali’s sense of the language has allowed him to turn Sir Andrew Augecheek into a mix of Louis Philippe and appropriator-in-chief Katy Perry circa “Dark Horse,” while Crawford’s Sir Topas masters the preacher’s whoop to exorcise a character who doesn’t need it.

It’s a take on the text that gives Viola all the agency and due she deserves. In the role, Ingram lets the words envelop her; she finds old comfort and new richness in their context. By the time she is describing the difference between male and female love her whole body has slipped into it, acutely aware of how physical her character’s humor can be.

When she realizes that Olivia (a dynamic Tiffany Denise Hobbs) loves Cesario—who is Viola, dressed as Sebastian—it has all the halted breath, humor and revelation the words (“She loves me, sure!/the cunning of her passion invites me in this churlish messenger”) have been waiting for. Other characters follow: Maria is clownish but also smart and no-nonsense, willing to play dirty when she can’t play fair anymore.

Olivia is aware of her power and uses it, her every entrance and exit bringing glimpses of a world we want to see. She stands on sturdy ground until love sweeps her unexpectedly off it, and this melty, whiny, just-slightly-vulnerable version is just as much fun to watch.

| Tiffany Denise Hobbs as Olivia and and Moses Ingram as Viola in Twelfth Night. Joan Marcus Photo. |

On one hand, that’s the point of Shakespeare: the text is timeless. We should be able to find Illyria in antiquity or in the seventeenth century, in Ingrid LaFleur’s real-life vision for Detroit or in Wakanda. But on the other, it is also a reclamation: Shakespeare has been claimed unfairly by the white canon and been a participant in its toxicity (The Tempest, anyone?). A cast composed entirely of people of color takes him back. These actors say, with equal parts humor and beauty, “this belongs to us too. It always has.”

All of a sudden, there’s an added layer to lines that praise complexion, or to characters who play into stereotypes, particularly those who make themselves pliant and overly accommodating in their own subservience. When Malvolio (a winning and intensely physical Allen Gilmore) states “Not black in my mind/though yellow in my legs,” he takes a minute to chew on the first part of the sentence.

Beyond that, it’s a celebration—of Black bodies existing in space, of their pursuit of love and also laughter. Because the language is there, everything else falls into place. On Illyria’s blank slate, scenic designer Riw Rakkulchon has found his inner vibranium and run with it, with a set that marries rising platforms, minimalist palaces, and a techno dreamscape from the near future. It comes to life with the help of Brittany Bland and Samuel Kwan Chi Chan, projection and lighting designers who have fused visions of a tech utopia with simple, slick choices that pitch the audience into a future that seems not so far away.

| The cast of Twelfth Night at the Yale Repertory Theatre. Joan Marcus Photo. |

With flair and literal shine, costume design from Mika Eubanks pulls from high fashion, minimalism, and bright batik, wax and kente fabrics to give a sense of royalty and magic. When we meet Olivia, she wears a glinting, beaded collar and glittering hair wrap that marks her as close to a literal queen. Her ladies-in-waiting are other worldly, in bright blue lipstick and turquoise platform sandals that somehow look good with white socks. Eubanks speaks the language of costume and comedy too: the audience learns that Malvolio sleeps in both a bow-tie and do-rag, which fits the fret and fuss of his character.

Against it, kinetic choreography from Byron Easley turns this Illyria vibrant and raucous, a place that needs to exist in the real world, but still feels aspirational in a country where white nationalism goes largely unchecked. In a final number that blends elements of waltz and African dance, Easley cracks the whole thing open, characters’ joy slowed down and dripping off the stage before it picks up, and the lights go down for the night.

This is the Shakespeare that New Haven, two-thirds of which is not white, has deserved for years. It goes beyond representation, and into the realm of possibility and best outcomes. It is belly laugh funny and full of heart, with lines that hang in the air long after the final bow is over. No wonder, than, that an opening night performance last week included multiple shouts of “Yasssss Queen!” several deep, rolling mmmms and an unplanned tambourine accompaniment from Row E.

Indeed, it channels the words of the play itself. No one in the cast needs to have greatness thrust upon them. They are great to begin with. They were born great. All they ever needed was a stage.