Downtown | Arts & Culture | Theater | Yale Rep Theatre | Public Health

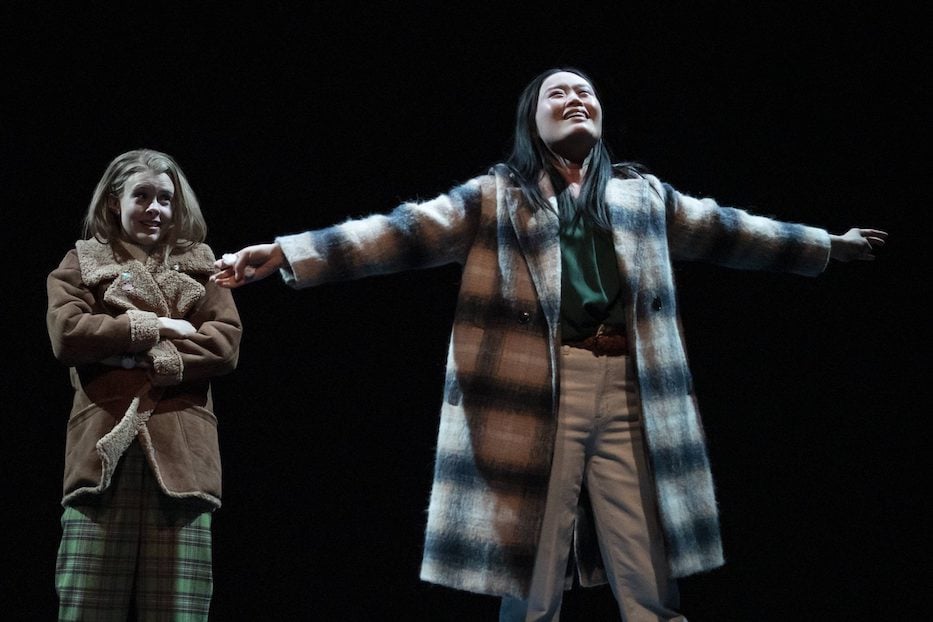

Michele Selene Ang and Katherine Romans in a scene from The Brightest Thing In The World by Leah Nanako Winkler, directed by Margot Bordelon. The show runs at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Dec. 17. Joan Marcus Photos.

Lane leans back into Steph’s arms, her face full of light. Her eyes are soft, trusting; they will themselves not to blink. Steph cradles her, looking down in awe. Around them, the whole universe has split open, and the sky is spilling stars. This is the calm before the storm, and there’s a sense that they’ll weather it together.

Will they, though? Does love ever really stay like this, in a dewy half-glow? Where do they bend, and where do they break?

That tension between dream and reality hums through The Brightest Thing In The World, now running at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Dec. 17. Written by Leah Nanako Winkler and directed by Margot Bordelon, the work takes on addiction, emotional dependency, and the complexity of human relationships all in the span of 100 minutes. By the end, it’s the mash up of Waitress, Trainspotting and The L Word that you didn’t know existed.

The show, which marks a world premiere of the work, runs at 1120 Chapel St. through December 17. Tickets and more information are available here.

Michele Selene Ang and Katherine Romans in a scene from The Brightest Thing In The World by Leah Nanako Winkler, directed by Margot Bordelon. The show runs at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Dec. 17. Joan Marcus Photos.

Set in downtown Lexington, Kentucky between 2016 and 2019, The Brightest Thing In The World follows baker/barista and aspiring MFA student Lane (Katherine Romans) and arts reporter/florist Steph (Michele Selene Ang) as they meet at the Revival Cafe, a sort of analogue to the real-life Recovery Café Lexington. The setup lends itself to a warm, sugar-glazed meet cute, where vegan cinnamon rolls come with puppy-eyed glances, witty barbs, and rambling half-critiques of NPR.

The two share a sweet, self-conscious flirtation, dipping into topics that range from body positivity (spoiler: butter is better) and righteous female rage to gun reform, pre-mittens Bernie, and their thoughts on the upcoming presidential election. “I feel optimistic about 2016,” Steph declares, and it’s a tempered, cheeky laugh line that the whole audience is in on. Winkler has a dry and offbeat sense of humor, and she’s at her best when she’s showcasing it.

But just as the audience is settling into a blessedly queer riff on Waitress, it quickly collides with the reality of living in 2016. Both Lane and Steph have baggage—opioid addiction, layers of family drama, parental relationships that teeter precariously on the edge of despair—but both endeavor to push past them. Fold in Lane’s sister Della (Megan Hill), who adds a question of which addictions are seen as acceptable and which are not, and there’s a full recipe for the show.

Or at least, the semblance of one, as if Winkler is cooking with flax and aquafaba even though there’s a carton of farm fresh eggs in the fridge. As a fumbling, then smitten couple, Ang and Hill are fun to watch. They orbit each other like excited electrons, then get heated and hurt just as quickly. Winkler mines the script for humor, and it comes in delightful, sometimes unexpected fits and starts.

Katherine Romans and Megan Hill in a scene from The Brightest Thing In The World by Leah Nanako Winkler, directed by Margot Bordelon. The show runs at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Dec. 17. Joan Marcus Photos.

Lane gets wonky and sharp-tongued around white male violence, and can pivot just as quickly to the intricacies of baking. Steph nails her self-conscious sexual hangups, which come out as halting innuendo. For a while, the flow of dialogue feels natural, if still closer to a rom-com than real life.

It’s when Winkler strikes a choppier rhythm that things get interesting, and sometimes messy too. Scenes are swallowed up in dream-like sequences that turn to cooling nightmares. Whole blocks of time disappear—first days, then weeks, then months, then a year—largely unaccounted for. It mirrors, with stage direction and speech alike, the very real rollercoaster of substance use disorder and addiction, where time becomes fungible and slippery.

Some of these tears in the play’s temporal fabric work—they unfix an audience in time and space. Bordelon is a nimble director, and crew members Cat Raynor (scenic design), Graham Zellers (lighting design), and Emily Duncan Wilson (sound design) turn the stage into their playground, telegraphing with the tools at their disposal the physical significance of touch, of sex, of feeling in one’s body, or not in it at all.

It is often a visually sumptuous work: set pieces move and glow, bouquets of flowers spring up and fall from the sky, fireworks stretch and sing across the stage, and whole universes reveal themselves one at a time. The production team plays off the trio's discordance of light and dark, of recovery and addiction, of steps forward and steps back, all through set dressing. Nowhere is it clearer than in Della’s apartment, one hub of recovery where it looks like Santa threw up on the furniture.

Katherine Romans and Michele Selene Ang in a scene from The Brightest Thing In The World by Leah Nanako Winkler, directed by Margot Bordelon. The show runs at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Dec. 17. Joan Marcus Photos.

But if an attendee is hoping for something that feels new or teachable, this play isn’t it. Opioid abuse is never a not timely topic—it killed a recorded 1,219 Kentuckians in 2015, and that number has continued to rise in the years since, according to the Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center. Many in the audience can likely name at least one friend or family member that has battled substance use disorder and specifically opioid addiction; some may even be that person.

And yet, there’s something about this play—the translation and delivery of that message—that doesn’t quite stick the landing. When Winkler writes about addiction and recovery, the language often veers into lyrical territory, as if her characters have suddenly found themselves at the College Unions National Poetry Slam. Lane, for whom pain meds opened a familiar gateway to heroin, seeks to blur the line between craving, being high, crashing, and entering recovery, but doesn’t always get there because she’s too busy getting lost in how lovely it sounds. Della, who is never far from a fog of grief, never graduates from the realm of sketch to fully-formed character.

At least once, fellow addicts become laugh lines. As she leans back into Della’s embrace, Lane mentions “Fingerless Frida,” an opioid addict whose plight is delivered as the butt of a joke. Romans knows it’s not entirely funny—maybe that’s supposed to be the point—but eggs the audience on anyway with a series of sharp, pregnant pauses. In a play that is supposed to eliminate the emotional distance between a viewer and their subject, it suddenly widens the gap.

“Her nubs are etched in my brain forever,” Romans said to a wave of laughter on opening night last week. And then as if an afterthought: “Opiates fuck up so much shit. I’m so lucky I still have my hands. And my teeth. Wish I could share them with Frida.”

It doesn’t entirely work half a mile from the Green (or, for that matter, a mile from the APT Foundation), where the city saw over 100 K2 overdoses in under 48 hours in 2018. In fact, it kind of smarts in New Haven, where seeing and interacting with opioid addiction is a part of existing in the city, and it doesn't look like this at all. Bordelon has described the show as a pre-pandemic time capsule, but if this show is a recent period piece, a quaint museum of where we were six years ago, how much has changed?

Instead, there’s this question that lingers in the air long after the lights have come down. Who is this play for (likely not Fingerless Frida)? People who will pay up to $65 a ticket to watch a play about opioid addiction, but have never taken the Congress Avenue bus? The riders on that bus, who might see glimpses of themselves in Lane and Steph, but still feel eons away? The New Haveners, and the Lexingtonians, and the people all over this country, who are the caretakers, the lovers, the people precariously in recovery?

Will they see themselves reflected on this stage? What do they do to numb themselves when the lights go down, and the world is still not what it could be?