Downtown | Ely Center of Contemporary Art | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | COVID-19

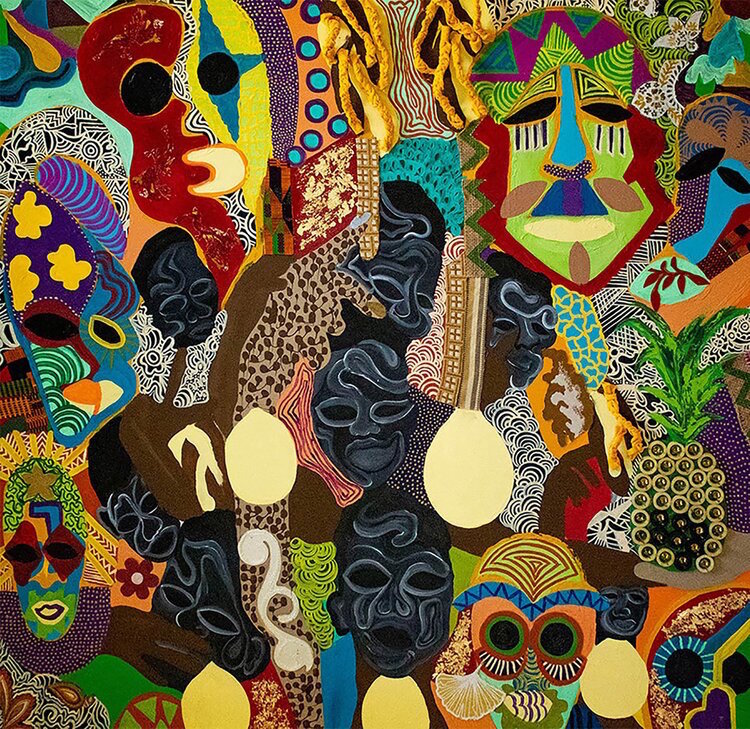

Left: Atlantic Senses, 2020. Right: Rooted Reflections, 2020. All paintings by April Fitzpatrick; photos from the exhibition.

The face looks forward in profile, eyes closed. There’s breath there, maybe prayer. Beneath a raised crown, smudges of blue, green, and red criss-cross the figure’s cheeks and forehead, migrate down their neck and back. They are land masses, bodies of water, a map unspooled. If a viewer looks closer, they can see spindly bodies, some pressed close together and others held apart.

In the background, yellow stamps vibrate up and down against a sea of black. It takes a moment to register them as pineapples.

April Fitzpatrick’s Atlantic Senses has travelled from Tallahassee to New Haven via Digital Grace, the online exhibition series at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. Her solo show, The Pineapple Metaphor: Expanding The Narrative runs there virtually through Feb. 8. For the next month, Digital Grace is also home to Urban Escapade in an accompanying virtual gallery.

The Ely Center is also holding the The Transart (notso) Short Fest and Solos 2020 through Feb. 21 at its Trumbull Street building. Hours and more information are available here.

“The Pineapple Metaphor: Expanding the Narrative is a conversation between myself, people, and place, using art as a paradoxical intervention to address racial trauma at its core,” the artist wrote in a statement that accompanies the exhibition. “I weave historical narratives of the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, and Souls Grown Deep, welcoming a critical view of one’s Lebenswelt (life-world) impacted by direct and indirect societal ills.”

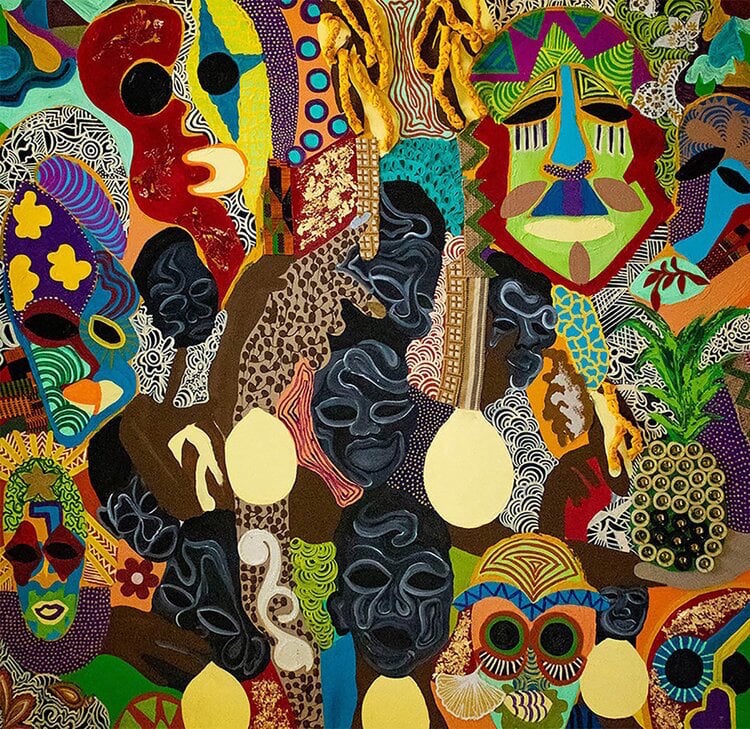

Left: America Was Never America To Me, 2020. Right: Sight, No Vision, 2020.

In her work, the pineapples are a healing device: they temper the bitterness and weight of history with an explosion of sun-colored sweet. They appear where a viewer may least expect them, woven tightly into a work or waiting to be noticed in shades of butter and canary yellow in the background. They show, in just a dozen works, how richly complex both the fruit and the artist are.

In Sight, No Vision, for instance, they blend coyly into the background, a quiet presence until suddenly they’re not. At first glance, a viewer may not see them at all: there are four large, unblinking eyes at the center of the piece. Each becomes a face, staring out at the viewer as they try to arrange this mix of eyes, limbs, and noses into a body that they can recognize. When the pineapples emerge, scored neatly and orbiting the figure, they become impossible to un-see.

Fitzpatrick also isn’t afraid to let viewers wrestle with her power of suggestion. In her America Was Never America To Me, she folds a reference to Langston Hughes’ “Let America Be America Again” into something entirely of her own creation, letting the poet speak both to and through her work. In the painting, a figure looks out to the viewer, their eyes half-closed as they open their mouth. Their hands, brown and outstretched, fill the foreground.

Something has caused a schism here: their face splits into sections of brown, yellow, blue, green and red. It’s not clear if the viewer is hearing a scream or a wail or something else, but the sound nearly makes it off the canvas. Each nail is painted with a silhouette in black, in what feels like a love letter to the artist Kara Walker.

Around the figure, the painting bursts into bright, cacophonous color, as if calling in Hughes’ own cry “O, let America be America again—/The land that never has been yet—/And yet must be—the land where every man is free.” A bright, heavy pineapple floats in the background, its crown severed from its body by the figure’s head.

Left: Behind The Flag, 2020. Right: Hidden From View, 2020.

The exhibition, in turn, feels like a history lesson, a call to liberation, and a balm rolled into one. In Atlantic Senses, Fitzpatrick’s layering of acrylic paint, fabric, and found objects gives the work a sort of haptic quality even through a screen (the actual canvas is 20 x 24 inches; the image on a screen is much smaller). On the figure’s neck, paint the colors of turmeric and red earth runs along either side of a raised round gold barrier, spikes sticking out in each direction. There’s a desire to spend time with the piece, teasing out each mark the artist has made.

So too in Behind The Flag, in which the American flag appears in the upper half of a canvas, partially covered by a collaged face. Fitzpatrick has pulled from the history of quilting—a scrap of kente cloth runs down one cheek, as tidy, geometric quilting squares appear in the figure’s left and right eyes. Two pineapples sit tidily where dangly earrings might in another world. Below, rolled and stacked newsprint runs alongside collaged news photographs and clippings, as if spelling out some of what the flag could not say on its own. Two daisies bloom defiantly in the chaos, rising from the canvas.

In this work and others, Fitzpatrick marries venerated craft and tradition with searing social commentary. The face, like the flag, looks as if it is on the precipice of unraveling: its forehead cracks as smears of bright yellow show through on the cheeks. It’s particularly striking as it comes to the Ely Center this month, in the midst of discussions, debates, and divisive partisan violence around who gets to represent America—or at the very least, the idea of America—and how.

While works in the exhibition were completed last year, their collective nod to the breadth of a diaspora defies any sort of timestamp. In one moment, a viewer may hear echoes of music, poetry, and scripture flowing through the canvases. In another, they may catch a glimpse of contemporary artists Joscelyn Gardner, Kehinde Wiley, or Wangechi Mutu. There’s a synergy with New Haven’s own Shaunda Holloway, whose solo work ran through Digital Grace last year.

It’s also a reminder of the multiple, layered traumas that Fitzpatrick—and artists who have tread the same path or now follow in her footsteps—is working through in a world turned completely upside down. There is the COVID-19 pandemic, which has proved far deadlier for Black Americans than their white peers. But there is also a much deeper trauma—that of stolen people forced to cultivate stolen land.

April Fitzpatrick, Lamp To My Feet, Light To My Path, 2020.

In her work, a viewer can trace echoes of enslavement and economic deprivation from the seventeenth century through the present. Without ever using words, she looks unflinchingly at the never-ending loop of white supremacy that is the foundation of this country, and most recently drove domestic terrorists, QAnon supporters, and Nazi sympathizers to the U.S. Capitol Building last week.

But The Pineapple Metaphor is ultimately hopeful: it presents viewers with pain and its root causes, but also with the antidote. In so doing, Fitzpatrick depicts a personal pathway to healing. At the Ely Center, it warrants a second, and third, and fifth close look.

“The fruit’s vibrancy urges viewers to create a new memory; that of the pineapple, a positive memory not bound by trauma,” she wrote. “I want my audience to see my use of symbolism as a way to capture a snapshot of their own individual trauma and marry it with healing. I use the collective nature of the pineapple to help us reframe our memories, reclaim our narrative and tell our story our way.”

Find out more about online and in-house exhibitions at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art here. The center has rolled out public health guidelines that all in-person visitors must follow due to the COVID-19 pandemic.