Culture & Community | Faith & Spirituality | Arts & Culture | News From The Pews | COVID-19

| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

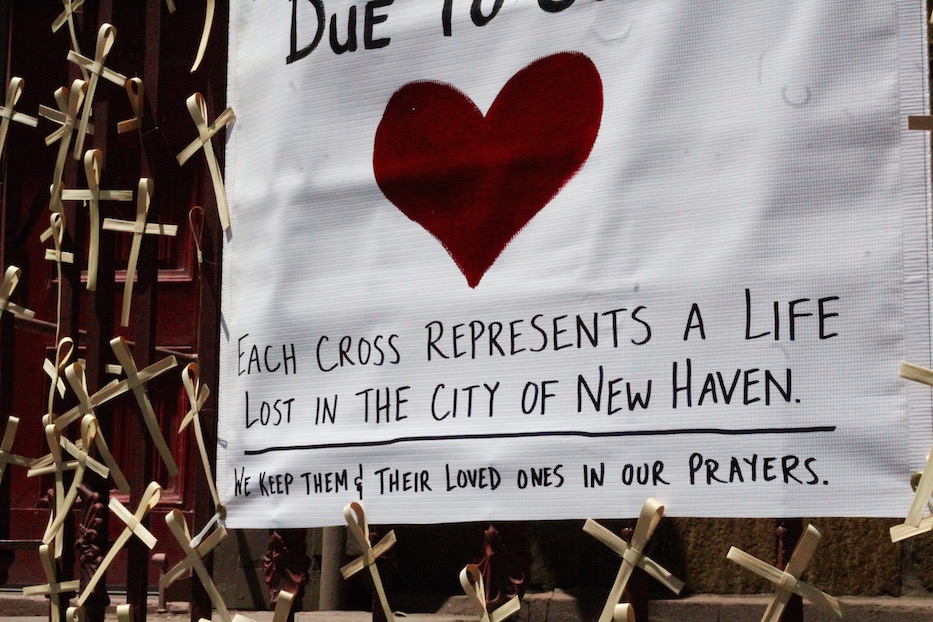

The first shape catches one’s eye from the corner of the New Haven Green, just beyond where the 265 bus comes to a rolling stop with yellow caution tape and pictures of masks on its doors. Then a second, sun bouncing off of its straw-colored body. Then a third, tied onto the fence in exactly the same style.

There are dozens and counting, tidy palm crosses for every life lost to the coronavirus in New Haven.

Last week, Trinity Church on the Green mounted 90 crosses to mark the first 90 deaths from COVID-19 in New Haven, a number that has since risen to 100. The brainchild of Assistant Rector Rev. Heidi Thorsen, they sit just outside the church’s front steps, on a black iron fence with a hand painted sign in red and black.

They are only a small part of the church’s pivot to online services, socially-distanced food distribution, phone-based spiritual support and ecumenical collaboration as New Haven reels from the virus.

“When I try to put a word to how I'm feeling, the word that I come back to is powerless,” Thorsen said in a phone call on Friday. “And I think everyone is experiencing powerlessness these days. Usually, we’re right out there with the folks on the Green, but right now I feel like we can’t be.”

Both Thorsen and Rector Rev. Luk De Volder have been thinking about a memorial for weeks, as COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths rise in New Haven. Before the virus, Trinity held “Chapel On The Green,” a weekly Sunday afternoon service on the upper New Haven Green. After the service, volunteers and church staff would serve a meal. By late March, the church had transitioned to to-go sandwiches.

| Lucy Gellman Photo. |

But the area around the sandwiches remained crowded, Thorsen recalled. She and other staff “felt like we were doing more harm than good,” and stopped distribution to stem the potential spread of coronavirus. In the weeks since, the church has reallocated resources to the Coordinated Food Assistance Network (CFAN), which actively works with soup kitchens and food pantries to get food to those who may need it most.

It has offered spiritual guidance over the phone and the internet, with varying success. Zoom, for instance, crashed in the middle of Sunday worship a few weeks ago.

The church is also working with local churches and synagogues to assemble packages with soap, socks, drinking water, items of clothing and word searches and crossword puzzles, for both the physical and emotional needs of many who are experiencing food and housing insecurity. The first of those packages, which have been assembled with the support of Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel (BEKI) in Westville, will be distributed at the Downtown Evening Soup Kitchen on Sunday.

“That is the necessary work, but is it necessary that we are in the church to do it?” Thorsen said. “No. People can call us if they want to talk, and pray over the phone. We're thinking of ways to connect.”

One of those has been the memorial. After the city’s first documented COVID-19 death in late March, De Volder began to place wooden crosses outside the church. Many of them disappeared. Thorsen’s mind went to the hundreds of palm crosses stored at the church. COVID-19 meant that Trinity was empty for Palm Sunday this year, for the first time in decades.

When they disappear—and already they have—Thorsen said she figures that people need them more than the church does. She and De Volder are working to update the memorial accordingly.

She added that the location feels fitting: the fence was once home to an LGBTQ+ pride flag that was torn off in an act of vandalism last summer. The flag was replaced by a sign that read “Hate Has No Home Here.” The fence, recessed from a bus stop and benches, has become a sort of de facto spot where the church shares its beliefs with all who pass.

“Since the churches are closed and we cannot make any verbal expressions of care, we wanted to make a visual expression that we are not forgetting this moment,” said De Volder. “Every cross is a life.”

“To See With The Eyes Of Our Hearts”

Thursday, the church also brought that message into a virtual sphere with its “Ascension Evening Prayer for Justice,” an Ascension Day service with Trinity, St. Thomas's Episcopal Church, St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, the Episcopal Church at Yale, and St. James Episcopal Church in Fair Haven.

The group was also joined by James Cramer of Loaves & Fishes, which is run out of the Church of St. Paul and St. James in Wooster Square. The nonprofit, which provides food pickup and pantry delivery out of its Wooster Square home, has seen a need for food grow by 300 percent during the pandemic.

Ascension Day, which takes place 40 days after Easter, marks Jesus’ ascent into heaven to sit at the right hand of God. This year, the church replaced its traditional in-person worship with Zoom, complete with congregants singing from their living rooms, in front of their home keyboards, and inside one empty church, where the organist played in a surgical mask as a single vocalist belted in the loft above.

“Let’s just pause for a moment and think about all of us gathered throughout the city of New Haven,” said Thorsen. “Across different neighborhoods and across different communities, and to think of how amazing it is that we are somehow all held together in faith. Held together by God, who calls us to be a part of something bigger than ourselves.”

Amidst a few slow internet connections, technological glitches, and muted microphones, a Zoom sermon took shape. The Rev. Kyle Pedersen focused on Jesus’ advice to his disciples: “Stay in the city, for in the city we will be filled with the holy spirit and become witnesses.”

That was thousands of years ago. Pedersen, who works at the Connecticut Mental Health Center (CMHC), pivoted to the present. He recalled a recent conversation in which a colleague told him that the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t exposed anything she already didn’t know about racial disparities and access to equitable healthcare. She is Latinx. Pedersen is white.

“COVID-19 has simply thrown gasoline on a fire that was already burning,” he said. “And in New Haven, we can see that a disproportionate number of people of color have been infected and have died, and that the city’s hotspots are low-income communities, mostly people of color.”

The data shows the same pattern. On April 20, the city released a heat map showing that Black city residents comprised 41 percent of coronavirus-related hospitalizations and 50 percent of coronavirus-related deaths. Latinx residents comprised 23 percent of coronavirus-related hospitalizations and 14 percent of coronavirus-related deaths. The city, meanwhile, is approximately one-third Black, one-third Latinx, and one-third white.

As of May 18, Black and Latinx residents still comprised the majority of documented, COVID-19 positive cases in the city. While Black city residents accounted for 28 percent of COVID-19 positive cases, they comprised 43 percent of virus-related hospitalizations and 45 percent of deaths.

Latinx residents also accounted for 28 percent of positive cases, but made up 26 percent of hospitalizations and 12 percent of deaths. A fourth “unknown” category accounted for 30 percent of COVID-19 positive cases.

Pedersen heeded words he had heard not from the Gospels, but from Wesleyan Professor Anthony Hatch, who has spoken out on the patterns of racial and socioeconomic discrimination laid bare by COVID-19. In a panel discussion on COVID-19 and health disparities, Hatch suggested that he doesn’t want to go back to normal “if normal is more inequality, more social and economic injustice, more health disparities, or any number of life draining, death dealing forces that are and have been devastating people of color.”

Pedersen urged listeners to reflect on those words—and this specific moment—as witnesses themselves. As of Monday, coronavirus had claimed 100 lives in New Haven and was still climbing. It has reached almost 1,000 people across New Haven county, and surpassed 3,600 in the state.

Meanwhile, Gov. Ned Lamont has launched a phased reopening of the state’s economy. Restaurants have started operating with access to outdoor dining and disposable silverware. Some shops have reopened their doors, with rules on how many customers can enter at a time. The grinding gears of late-stage capitalism have clicked back on.

In one universe, the disciples were still staring open-mouthed at the sky. In another, it was late May in Connecticut, and the governor had pushed the state towards a normalcy that no longer exists.

“We may be wondering along with the disciples: Is now the time?” Pedersen asked aloud. “Is now the time for the restoration of the kingdom? Is now the time for this oppression and exile to end? Is now the time that we can go back to lives that we once knew? Go back to normal?”

“To be a witness is not only to be able to see with the eyes in our heads, but also the eyes of our hearts,” he continued. “To be a witness is to be able to perceive sensual reality—what we can see, hear, smell and taste—and spiritual reality. That which touches the core of our being. To be a witness is to be fully present. Right here. Right now.”

As dozens of parishioners listened through their screens, he urged them to use that power—as “healers and witnesses for justice”—to counter the structural racism and inequality that plagues both New Haven and America.

He drew on the twelfth century medical writings of Hildegard of Bingen, who identified a kind of nature-influenced life force called viriditas that is most vibrant when it is physically sustained and free of that which binds it.

“We are healers and witnesses to justice when we see and prune away the strangling structures of racism, poverty, economic enslavement, and discrimination that lead to sickness and death,” he said. “We are healers and witnesses to justice when we acknowledge with humility our blindness, our prejudice, or failure to see and undo the hurt and harm that’s all around us.”

“Now is the time to stay in the city,” he continued. “Now is the time to open wide the eyes of our hearts. Now is the time to be filled with the holy spirit, and witness to the life force of God’s justice.”

To listen to the full sermon, click on the video above. To find out more about Trinity Church on the Green, visit them on Facebook, on YouTube, or at their website.