Kehler Liddell Gallery | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts

| A detail of one of Martson's Photos. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

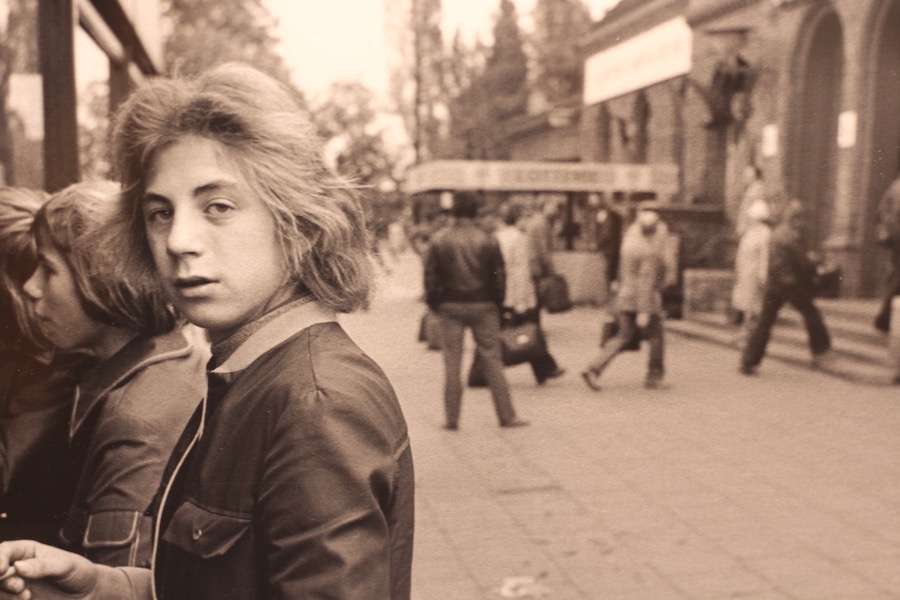

There’s a sense that the frame is in motion. At the right, a trickle of bodies heads into what looks like Berlin Schönefeld airport, the clip of feet almost audible from where they fall. A man straddles the center, unsure of where he’s going. At the left a teenager meets your eyes. He’s 13, maybe 14. A cigarette dangles from his right hand.

No one is there to tell you that this is inside the Deutsche Demokratische Republik, the oppressive government that starved, tortured, killed, and spied on citizens of East Germany from 1949 to 1990. Nobody seems to care. Across the room, a deep gray sea creature sits at attention, unaware and precarious. One end, shaped like a power drill in mid-spin, splits the air around it.

These unlikely pairings meet in TAKING SIDES — Berlin and the Wall 1974 and Canaries In A Blue Coal Mine, installed together at Kehler Liddell Gallery through Oct. 6. Worlds apart until they’re suddenly not, the two exhibitions place photography by Sven Martson alongside marine sculptures by Gar Waterman, initiating a surprising conversation between two longtime New Haven artists.

| One of Waterman's mollusks. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

At first glance, TAKING SIDES and Canaries in A Blue Coal Mine have little, or maybe nothing, in common. While Waterman’s sculptures wink out from the edges and center of the gallery, Martson’s images come from a divided Berlin that exists only in the past, taken during a month-long stay there in September 1974. The year marked the midway point in the Berlin Wall’s 38-year lifespan, splitting Communist East Germany, run by the German Democratic Republic or GDR, and ostensibly more liberated West Germany, run by the Federal Republic of Germany.

Armed with his American passport, Pentax Spotmatic and three lenses, Martson was able to pass freely between the two, a luxury not afforded to Germans themselves until the wall fell in 1989. While residents of the East risked death if they tried to escape, he found himself popping over there for cheap lunch, then spending the afternoon back in the West to take more photos.

He first travelled to Germany, he said, “with the intention of making East Germany look bad,” thinking that West Berlin would have a certain palatable sparkle and joie de vivre. Instead, he discovered citizens, torn apart by state-sanctioned barriers, that had a lot in common.

“It was a random walk around the city for a month,” he said Wednesday, finishing the install for his show. “People were living their lives. They went to work, had breakfast, had dinner, went to bed.”

| Details from the installation. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Except, a big wall cut through the city like a scar, separating families and friends for almost four decades. Several of Martson’s photographs have a sense of the lives lived in limbo: teenagers chat and smoke and have no idea that Berlin will be unified by their 30s, siblings carry each other down the street, people take the train to work and walk home from the stations. Families chat as they wait for Curry Wurst at a snack cart, residents sit back-to-back on park benches, a prostitute waits to pick someone up in a large city park.

It’s a city that looks remarkably calm for a period of immense postwar trauma, Cold War paranoia, and loss. At one end of the gallery, a mother and young daughter hug at the Schöneweide Rail Station in East Berlin, pressed up close against each other in their coats, stockings and heels. If we’re not familiar with the location—it’s only after reading an image sheet that we discover where they are—we might mistake it for any embrace, anywhere.The coats appear clean and fresh; there’s nothing knockoff or cheaply economy about the stockings. So too with siblings who walk down the street, or busy workers on their lunch breaks in a city park.

Until it isn’t anywhere, of course. For almost four decades, citizens of East Germany were plagued with starvation, poverty, and the psychological stress of secret surveillance under the state. If you know to look for it, there are signs that not all is well in this divided land: sleek mannequins pose with flashy clothes in the West, replaced by law enforcement officials and tight-lipped, baby-faced border guards in the East. In one particularly chilling photograph, Martson has focused on the ominous, unmistakable outline of an occupied watchtower in East Berlin, from which guards would shoot and kill or imprison anyone trying to get over the wall.

| Sven Marson Photo. |

There are subtle references, too. In one image, a Barbie doll waves out of a car’s dashboard, as if saluting a world of material goods and discretionary spending that can only exist on one side of the wall. In another, a woman leans her head on the U-Bahn’s rumbling siding, her eyes looking out the window as the train barrels on. Maybe she’s just had a long day, you reason. But there’s a creeping feeling she’s in the East—she looks exhausted, her face criss-crossed with worry and premature age. And indeed, an accompanying label sheet reveals that she is, a sort of close-up, twentieth century rendition of Honoré Daumier’s The Third-Class Carriage.

Martson said he wants to be clear about the show’s personal, documentary quality. The images reflect his experience of the city at a specific moment, as an American visitor with cashflow to offer in return for his freedom to stroll. These photographs fall into the rich tradition of street photography, not meant to replace any historical truth or act as photojournalism, so much as to archive a moment for the artist.

But as our guide, he’s an ever-curious one. Martson has his own experience with divided lands: he was born in Germany and spent the first years of his life in a displaced persons camp before coming to the United States in the early 1950s. Before taking up photography, he studied architecture and painting. So it makes sense, in a way, that he would focus on not just a structure splitting the city, but the people living their lives around it. And 44 years after the photographs were first taken, he said it feels timely to have it displayed in one place for the first time.

| Details from the installation. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

“This whole idea of the wall on the south end of our country strikes me as really bizarre,” he said, noting the number of deaths that sprang from the wall’s existence. “Did the Great Wall of China really work? Did Hadrian’s Wall really work? It’s the same dumb idea.”

It’s one that also ties in, if unexpectedly, with Waterman’s sculptures, dazzling marine specimens that dot the walls and center of the gallery. While Martson’s two-dimensional humans may be frozen in time, something about these shiny shells, sea stars and soft-bodied fish is urgent, a ticking clock almost audible in the background. With each grouping, Waterman introduces us to a different species, a label explaining how it has become endangered by global warming.

There are Waterman’s signature nudibranchs, whose bright appendages seem to sway from the center of the gallery. These creatures, we learn, are not of another world but ours, soft-bodied and sleek as they make their way through the seas. But not all is well in this world either: rising ocean temperatures, chemical pollution, and ocean acidification are putting the creatures’ delicate ecosystems at risk, as the coral reefs on which they settle and flourish are destroyed.

| Waterman's nudibranchs in the gallery. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

As Waterman’s label explains, scientists have seen a sharp drop in larval settlement on some reefs, because of lower pH in the oceans. And meanwhile, on land, humans aren’t stopping a global warming crisis that they still have power to halt.

You still can save me! two large, sleek sculptures at the center of the gallery seem to cry out. But are you willing to?

It’s an approach to these creatures, beautiful and alien, that demands a closer look. Near the front of the gallery, we meet wide-eyed cephalopods, a sort of cheeky pendant to three large photographs of border guards in the same corner. Beside the label, Waterman’s rendering of a Humboldt Squid looks out on the viewer, its long body ready to slip off the pedestal and swim off, cutting through the water with its massive body.

Like a citizen thrown into a new regime, it too is facing a changing world. As we learn, cephalopods may not be immediately threatened by climate change, but their patterns of migration are changing, and so too their lifespan.

| A giant Humboldt Squid by Waterman. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Take the Humboldt Squid, Waterman suggests. As temperatures fluctuate more wildly from hot to cold, squid populations have migrated, grown in size and been able to live longer, communities establishing new livelihoods around them. But just as easily as temperatures have created this trend, they could take it away. Across the gallery, an endangered, garnet echinoderm (starfish) lifts one tentacle just slightly, as if to agree.

If the pairing is an odd combination of colors and textures, it works to drive home a common message. Patterns of migration might change, but we have the power to react to them more kindly this time. Walls may be proposed, but we can protest them before they are built, or call for their removal. Temperatures are shifting, but we are still within a window where we can turn global warming around.

It’s not, in other words, all doom and gloom. There is an end to the pain we inflict on each other, and on our planet, because it is wholly preventable in the first place. It always was.

Sven Martson's TAKING SIDES —Berlin and the Wall, 1974 and Gar Waterman's Canaries in a Blue Coal Mine run Sept. 6 to Oct. 6 at Kehler Liddell, 873 Whalley Ave. The gallery is open Thursday and Friday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., Saturday & Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., or by appointment.