Exquisite River at the Ely Center for Contemporary Art. Photos Kapp Singer.

Exquisite River at the Ely Center for Contemporary Art. Photos Kapp Singer.

A silver foil fractal snakes across a crinkled, matte black surface. Hairline tributaries merge into a thick, reflective band. Across the room, two thin glass tubes—one shaped like the Quinnipiac River, the other the Housatonic—twist and turn.

In Exquisite River, a body of water becomes a body of work. On view at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art (ECoCA) until June 2, the group show brings together a wide variety of pieces about rivers from twenty artists in the Think About Water collective.

The show’s organization was inspired by the Surrealist game exquisite corpse, a collective figure drawing exercise where participants each illustrate a section of a body without seeing the contributions of others. For the exhibition, each artist crafted a section of a river in their studio by the same method.

Paintings, prints, sculptures, photographs, textiles, and films consider the geometry of creeks, seed dispersal in waterways, sediment deposits, dams, fisherman, and more.

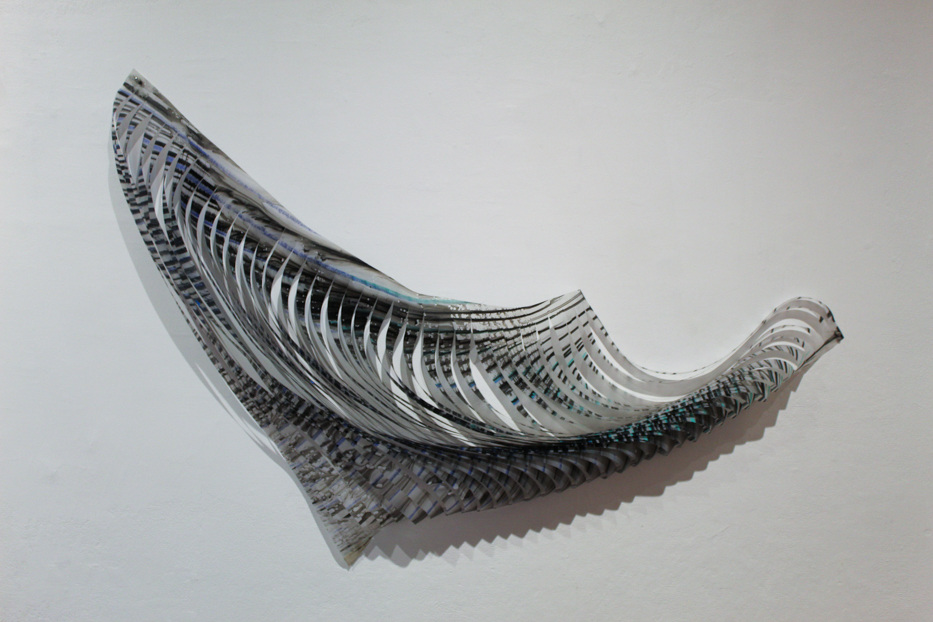

In Jaanika Peerna’s RiverFlow, a slitted piece of blue, brown, and white mylar cascades across the wall. Thin ribbons of plastic film twist and tumble, threatening to collapse into a chaotic mess before being caught by the intact edges of the sheet. The piece seems to highlight the contrast between the river’s body and its bank, that necessary tension between intractable fluid and solid ground.

Top: RiverFlow by Jaanika Peerna. Bottom: “Taroko” Liwu River, Taiwan by Doug Fogelson.

Top: RiverFlow by Jaanika Peerna. Bottom: “Taroko” Liwu River, Taiwan by Doug Fogelson.

The theme of folding continues in both Doug Fogelson’s “Taroko” Liwu River, Taiwan and Lisa Reindorf’s Mobius Strip Water. In the former, a top-down photograph of a rocky section of waterway is printed on fabric and undulates across the wall. Rapids and waves are augmented by neat corrugations. The latter similarly begins with a flat, rectangular depiction of a river. This vellum sheet, colored in oil paint, is then formed into a half-twisted loop, dissolving the distinction between inside and out.

Upstairs at ECoCA, a companion exhibition wonders what happens when rivers physically jump beyond their bounds. In the multimedia installation Flood 2.0, also open until June 2, artists Krisanne Baker, Susan Hoffman Fishman, and Leslie Sobel imagine a climate change-induced reprise of the Genesis flood (Hoffman Fishman and Sobel both also have work in Exquisite River).

A poem on the wall tells the story of a woman named Noa, the sole survivor of this apocalypse. “We were warned. Decades and decades ago. / There was inaction everywhere,” it reads. “I don’t have any companions two by two. / It’s just me. I am one.”

A kayak, affixed to the ceiling, is surrounded by dozens of painted paper scrolls. Everything is bathed in blue light and warbling music plays quietly. Two video projections fill the walls, playing a looping montage of footage of rushing rivers, hurricane clouds, and weather radar maps.

Flood 2.0 by Krisanne Baker, Susan Hoffman Fishman, and Leslie Sobel. Photo courtesy Susan Hoffman Fishman.

Flood 2.0 by Krisanne Baker, Susan Hoffman Fishman, and Leslie Sobel. Photo courtesy Susan Hoffman Fishman.

The installation was initially shown in 2023 in Torrington, a town with a history of flooding; here in New Haven, it seems to suggest that this city could meet the same fate as sea levels rise. On June 2, to conclude the exhibition, the artists, Dawn Henning, a city engineer, and Steve Winter, director of the city’s Office of Climate and Sustainability, will host a walking tour of the city’s flood infrastructure.

While Exquisite River and Flood 2.0 consider the role of water above the ground—and especially what happens when that water rises above normal levels—a recent exhibit at the Yale School of Architecture looks beneath the surface. Groundwater Earth: The World Before and After the Tubewell catalogs how the tubewell, a method for extracting water from underground aquifers via a pipe, has impacted urbanization and agriculture.

Curated by Anthony Acciavatti, a professor at the Yale School of Architecture, the show runs until July 6 in the school’s second floor gallery at 180 York St. It demonstrates how this modest technology has had extraordinary global implications.

Groundwater Earth: The City Before and After the Tubewell, curated by Anthony Acciavatti.

Groundwater Earth: The City Before and After the Tubewell, curated by Anthony Acciavatti.

The aquifers that the tubewell allowed humans to tap into contain up to 15 times the volume of global freshwater supply from all rivers and lakes combined. Unearthing this new source of life, the show demonstrates, entirely reshaped cities, from the design of individual houses to the layout of entire metro areas.

Its title suggests a comparative study of a pre- and post-tubewell planet, though the show primarily looks at developments after 1865, when the U.S. granted the first patent for the technology. Acciavatti, however, seems unconcerned with drawing stark chronological boundaries.

“The exhibition,” an accompanying booklet reads, “is less a biography and more an abridged travelog of the conception and global dissemination of the tubewell.” While Groundwater Earth does consider just a small sample of sites and moves relatively quickly between scales of analysis, it is not a cursory gloss. Acciavatti, who is trained as both an architect and historian of science, has been researching water infrastructure for nearly two decades. The show is the first comprehensive look at “how this technology came to allow billions of people to thrive but also threatens to bleed the earth dry.” Maps, diagrams, models, photographs, timelines, and a healthy dose of text fill the gallery.

Two specific regions are the primary focus of the exhibition: the Indo-Gangetic Plains—a fertile area covering much of northern region of the Indian subcontinent, defined by the Indus and Ganges rivers—and the Sonoran Desert—an arid expanse stretching between southern California and Arizona and the northern areas of the Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California.

The show elucidates the effect of the tubewell on life in these regions across four different modules in the center of the gallery. Each considers a different setting or scale: “House,” “Neighborhood,” “City,” and “Hinterland.” Models of “core samples”—cylindrical sections of earth—show the depth of aquifers across these conditions and how deep tubewells must reach to access water.

At the base of these columns are small dioramas showing, for instance, how the street grid of the Winterhaven neighborhood in Tuscon, Ariz. formed according to a series of shared wells; or how, in New Delhi, houses are commonly designed around a central courtyard with a hand pump.

A model of the Growing House, a typical housing typology in New Delhi—originally designed by Harold R. Hay—in which a home is laid out around a central courtyard with a hand pump.

A model of the Growing House, a typical housing typology in New Delhi—originally designed by Harold R. Hay—in which a home is laid out around a central courtyard with a hand pump.

While the Indo-Gangetic Plains and Sonoran Desert are the most extreme examples of landscapes altered by the tubewell, these are not the only areas of the planet touched by this technology. The exhibit also looks at Addis Ababa, Mexico City, and Jakarta.

But things don’t stop there. As the show’s introductory wall text strikingly points out, groundwater extraction has “altered the tilt of the earth.” In some sense, then, the tube well is beneath all of our feet.