Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | Wilbur Cross High School | Arts & Anti-racism

.jpeg?width=933&height=622&name=ArabicFestival2023%20-%201%20(1).jpeg)

Teacher Hanan Elkamah with students at the mosaic station. Bottom: Aydin Gasimov's display. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Just beyond the doors of Wilbur Cross High School’s gym, a photograph of the Kaaba beckoned, the cube draped in black, gold, and silver silk as it stood in the heart of Mecca. Beside it, an image of Dubai’s Museum of the Future rose up from the ground, covered in larger-than-life Arabic script that glinted in the sun. Nearby, Egypt’s pyramids appeared to commune with the Kuwait Towers, separated by centuries of history.

For sophomore Aydin Gasimov, all of the images represent a chance to learn more about his own history—and pass it to his peers.

Last Friday, Gasimov was one of dozens of student presenters at Wilbur Cross’ third annual Arabic Festival, held each May to fête cross-cultural exchange and a growing interest in Arabic language and history at the school. Organized by Arabic instructor Hanan Elkamah, the festival doubled as a chance for peer-to-peer teaching and a celebration of Cross’ diverse and multilingual student body.

The festival received support from both Cross and Qatar Foundation International, which provided a $1,000 educational grant. Elkamah, who currently teaches 97 students, also raised money with a henna fundraiser during Cross’ first “International Day” in March.

“This is to bring the school together,” said Elkamah, who immigrated to the U.S. from Egypt 27 years ago, and has taught Arabic at Cross since 2018. “To celebrate Arab culture, and to celebrate our similarities rather than our differences.”

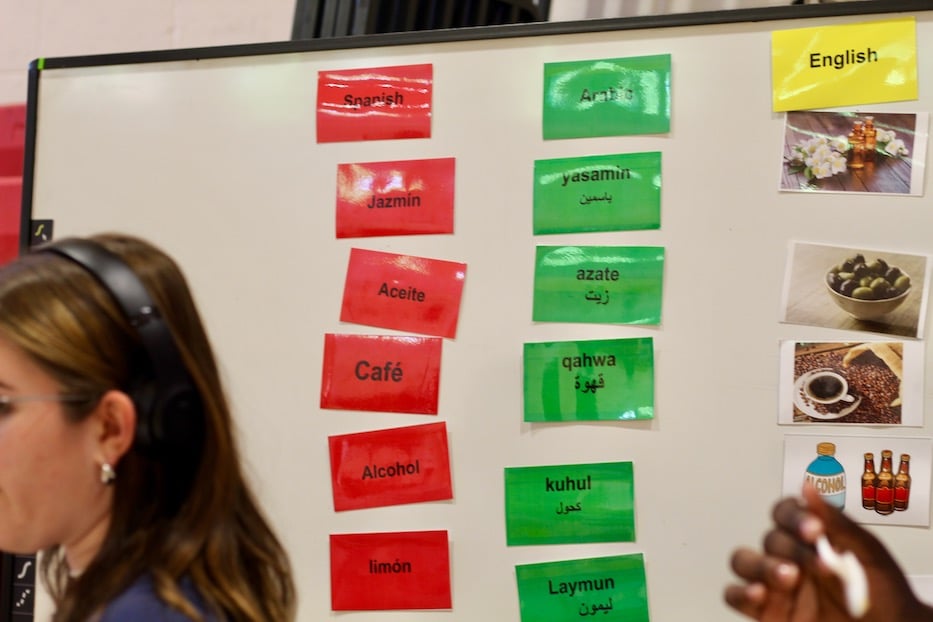

Among student posters for the 22 countries in the Arab world, the festival featured Middle Eastern cuisine, stations for hot mint tea and strong, thick black coffee, Egyptian and Levantine folk dancing, clothing displays, mosaic-making, and interactive displays that traced the origin of words in English and Spanish back to Arabic. As students milled around, strains of English, Spanish, Pashto and Arabic wafted through the air.

Near the gym’s front entrance, Gasimov chatted with his peers about the beauty and the breadth he sees in the Arab world, which he is studying as a student of Elkamah’s. Born and raised in New Haven, Gasimov is the child of immigrants from Azerbaijan, part of the former Soviet Union that sits between Europe and Asia.

Aydin Gasimov, who is a sophomore at the school. Lucy Gellman Photos.

While the country is not considered part of the Arab world, “it has a lot of Arab culture,” Gasimov said—including flowing Arabic script, centuries-old Byzantine churches and preserved palaces that he has noticed on his summer trips home to visit extended family. At home, Gasimov speaks a mix of Russian and Azarian English with his parents.

When it came time to pick a language in high school, Arabic seemed like the right fit. At school, Gasimov has noticed more newcomers to the country, some of whom come in speaking Arabic. He likes the history that Elkamah folds into her curriculum. He said that it also helps him to talk to his peers about Islam, and counter misunderstandings that they may have.

“I think people think that it’s a violent religion,” he said. “But there’s this saying in the Quran, it says, if you kill one innocent soul, it is as if you have killed all of humankind.”

A station showing the similarities between Arabic and Spanish words. Elkamah said she was inspired by the number of Hispanic/Latino students in the district, for whom Spanish is a primary or secondary language long before they reach high school. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Nearby, students Lesley Serrano and Anahy Nopal invited peers over to a new mosaic station, showing off an intricate, bright tilework star design before dipping into the rich history of mosaic art across and beyond the Arab world.

While the mosaic tradition originated in ancient Mesopotamia (now recognized as Iraq), they explained, the art form has spread across the globe. Behind them, images of Philadelphia’s Magic Garden, Barcelona’s Park Güell and Jordan Madaba Map all peeked out, taking students on a whirlwind tour without ever leaving Mitchell Drive.

Serrano pointed to images that showed off the complexity of mosaic work, the designs often laid in delicate and painstaking detail. Even as a printout flattened the Madaba Map to two dimensions, it traced the contours of sixth-century Jerusalem, with tiny homes, deep blue ceramic bodies of water, and bobbing boats with deep, strong oars slicing through the water.

Top: Shantasia Hayes. Bottom: Students doing the dabke dance. Lucy Gellman Photos.

For both Nopal and Serrano, taking Arabic classes at Cross represented the chance to learn about a new culture. Serrano, whose family hails from Puebla, Mexico, said she knows firsthand how language can open a door to new customs and traditions, and make it easier to relate to people on their own terms, rather than asking them to assimilate. Because she already speaks English and Spanish, Arabic appealed to her; she said she finds it “really pretty” to speak and to listen to.

“It’s pretty nice,” she said. Across the gym, students held up a series of thick, brightly embroidered thobes, carefully stitched in gold and metallic thread. “The culture is different—the food, the art. Honestly, I just want to know more about Arabic arts and culture.”

Shantasia Hayes and Janae Nelson. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Across the gym, students Shantasia Hayes and Janae Nelson ran over the steps of an Arabic folk dance one last time before hitting the floor, shaking off their nerves as they prepared to perform for the student body. For Hayes, who is a senior, Arabic classes were a lifeline after she struggled in Spanish.

“The way Ms. Hanan teaches, you want to learn,” she said. “I just love the Arabic language and people. I feel like their culture is really welcoming.”

“And she makes the class fun!” Nelson added, with such enthusiasm that the silver coins across her waist and skirt seemed to nod in agreement.

When Elkamah asked if the two were interested in learning a dance for the festival earlier this year, the answer was an immediate yes from both of them. In the two weeks leading up to the event, both students worked with expert dancer Kelvia Mitri-Meda, founder and director of the Middle Eastern Dance Academy of Connecticut.

In previous interviews with the Arts Paper, Mitri-Meda—who is proudly Puerto Rican—has said it was Middle Eastern dance that helped her ultimately feel comfortable with her body. As the two prepared to move across the floor to blasting music, they said she'd helped them feel that way, too. Nelson, who is a junior at the school, added that she sees her peers who are newly from the Arab World—mostly Afghanistan and Syria—as “honestly more accepting than we are.”

“This is like, pure energy,” Nelson said. “It’s definitely a workout. You see how much they [dancers] put into it.”

“I love it,” Hayes added as the music crackled over the speakers, and she and Nelson headed to the center of the floor. “I feel like it’s outside of my comfort zone.”

FAME eighth grader Rosa Gonzalez and Arabic teacher Soha Osman, who also teaches at Celentano Biotech, Health and Medical Magnet School. Lucy Gellman Photos.

As she lifted her phone to record a video of them from where she stood, attendee Rosa Gonzalez scanned the room, watching as new and familiar faces from the Family Academy of Multilingual Exploration (FAME) and Engineering and Science University Magnet School (ESUMS) poured in for a visit. They gathered at the edges of the gym, some nibbling pita and hummus as they watched Hayes and Nelson float across the floor.

Now an eighth grader at FAME, Rosa started taking Arabic when she was in sixth grade, her third language after Spanish and English. For her whole life, she said, she’s seen language as a portal—first to communicate with her family from Chiapas, Mexico, and now to learn about countries that are half a world away.

If she could go anywhere, she said, it would be to Jerusalem, where Arabic is spoken alongside modern Hebrew, Russian, Yiddish, French and English. For her, she said, it would be meaningful both as a Christian and as a way to flex her language skills.

“When you learn new languages, you get to learn [about] other places,” she said. “You can actually travel.”

Reem Saood and Kelvia Mitri-Meda, founder and director of the Middle Eastern Dance Academy of Connecticut. Lucy Gellman Photos.

She turned back to the still-rolling camera on her phone, where Mitri-Meda had taken the floor, and was dancing with a long, curved sword in one hand. When Mitri-Meda beckoned to the young, mouths-agape crowd, Reem Saood stepped forward, and stood patiently as she balanced a sword atop her head.

A junior at Cross, Saood came to the U.S. as a refugee from Basrah, Iraq in 2004, when she was a very small child. She remembered how new New Haven seemed as Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) helped her family settle into their new home. Almost two decades later, she’s getting ready to apply to college with an interest in immigration law and human rights.

Taking Arabic and learning about her culture at Cross “has made me proud of myself,” she said. In and outside of school “I think people think of us [Iraqis, Muslims] as cold-blooded,” because what they primarily see in the mainstream media is war and conflict. “But our religion is very peaceful.” Taking Arabic, and learning from Elkamah, has helped her sort through some of those feelings.

Back inside the gym, a group of students came down from their performance of the dabke, a type of Levantine folk dance that has criss-crossed several countries in the Arab World. Farhad Maiwand, who came to New Haven from Afghanistan as a refugee in 2019, said that he was inspired to take Arabic after arriving in the U.S. with Pashto as his first language.

“It’s good,” he said, gesturing to activity stations as they unfolded across the gym. “We can share about our culture.”

Beside him, senior Murtaza Shahnan praised the festival as a way to connect fellow students with Arabic culture in a way that isn’t just about conflict. As an Afghan student who arrived in the U.S. as a refugee two years ago, he’s seen that students either don’t know what’s happening in Afghanistan, or only know about the Taliban’s abuse of power in the country. When it comes to Afghan history, most students draw a blank.

“This means connecting with our culture,” he said.