Culture & Community | Dixwell | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | History | Dixwell Community Q House | GNHAAHS

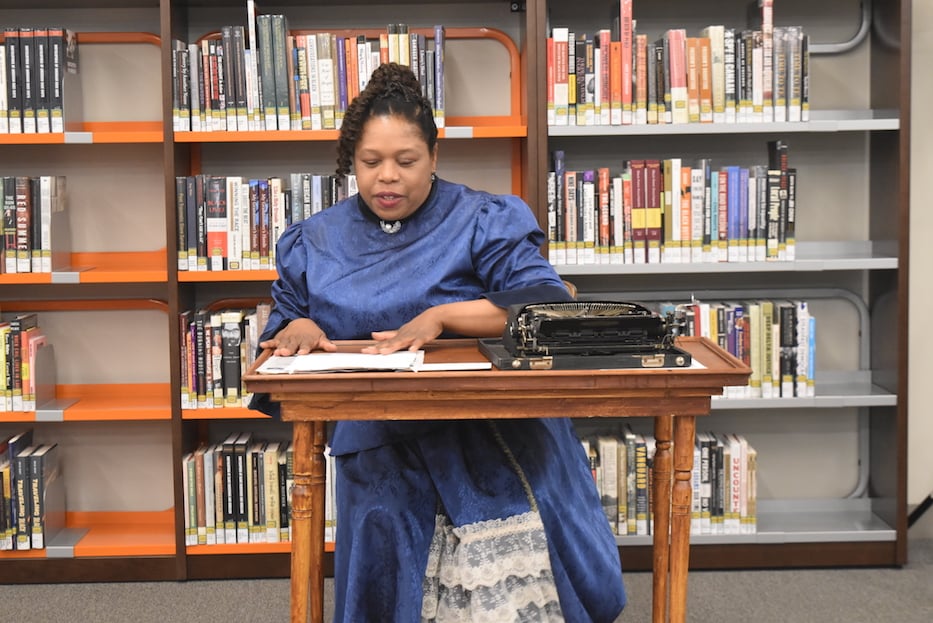

Dr. Karima Robinson as Ida B. Wells. Leah Andesmith Photos.

Standing next to the podium, Ida B. Wells wrung her hands with worry. The audience applauded as Frederick Douglass introduced the young speaker and she took the stage of New York’s Lyric Hall. She began tentatively, but quickly gained confidence, affecting both the audience and herself with the emotion behind her words.

“What America doesn’t understand is that the Negro is determined to be free and equal citizens in this country which we built with our bare hands,” she said.

This stirring moment was the climax of Karima Robinson’s performance as Ida B. Wells, held at the new Stetson Library on Sunday afternoon. “A Celebration of Women’s Voices," presented in partnership with New Haven Free Public Library and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, was the Greater New Haven African-American Historical Society’s first in person event since the pandemic began.

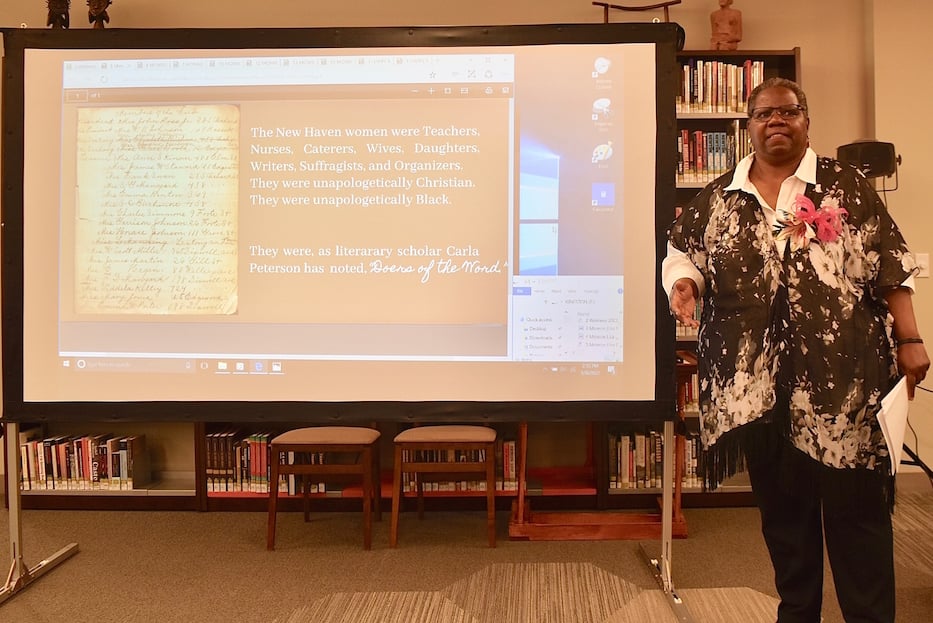

The program drew over 40 attendees and included a talk by historian Lisa Monroe, whose research centers on the minutes of the New Haven Women’s 20th Century Club between the years of 1900 and 1902. Those minutes are part of the James Weldon Johnson Collection at the Beinecke.

Lisa Monroe’s presentation. Leah Andelsmith Photos.

The Women’s 20th Century Club’s book of minutes begins with an origin story tying a group of civic-minded New Haven women to one of the foremost change-makers of the time:

March 18, 1900 Monday Afternoon

Mrs. J. Walter Steward of 65 Edgewood [Avenue] invited a number of ladies to meet Mrs. Ida B. Wells-Barnett and hear her talk on women’s club work. [After] an interesting talk of an hour it was decided to form a club…

Wells was a prominent anti-lynching activist, suffragist, journalist, and public speaker who lived and worked around the turn of the 20th century. She documented lynching cases in the South and reframed lynching as domestic terrorism used as a weapon to enforce white supremacy.

Wells believed in the importance of women’s club work to make a difference. By 1920, 50,000 African-American women were involved in women’s clubs, Monroe said. The movement may have grown out of church communities, but it offered women new opportunities for political and civic work outside of a religious context. Because of its location between Boston and New York, New Haven was a center for this kind of cultural and political activity, GNHAAHS Co-president Carolyn Brown said.

“Ida’s work put New Haven women’s club work on the map,” Monroe said. When Wells came to Mrs. Steward’s Edgewood Avenue residence to speak, she “was not someone coming for a polite tea. She was on fire.”

Meeting these New Haven women, Wells would have wanted to know: “Are you gonna be about it?”

Dr. Karima Robinson as Ida B. Wells. Leah Andesmith Photos.

The audience listened closely as Monroe read passages from the minutes. The women recorded preparing packages of necessities like firewood, coal, and groceries for families. They reported visiting the three African-American typhoid patients in the hospital and collecting donations of bed linens for them.

“Tell me what you think you hear about who they are and what they do. Put it in your own words,” she invited the audience. Local educator Arden Santana spoke right up.

“They were making sure the elderly, sick, shut-ins, and those in need weren’t forgotten and were taken care of,” Santana said. Others agreed that the women’s club “had their eyes and ears in a lot of different places,” using their social connections to find out who in the community needed assistance.

“Have you peeked at my research?” Monroe joked.

When one audience member observed how organized and professional the club was in keeping these minutes, another added that the women “were more than just organized. They were future oriented,” leaving a written legacy that we are poring over today. Still another pointed out that the club’s principles of collective work, responsibility and unity had its past in Southern Black communities.

Monroe made the work of historians accessible to everyone in the audience, and led them in doing that work right there in the moment. She made it clear how personal and present this history is for her.

“I met these women ten years ago in the Beinecke library,” Monroe said, recalling the day a professor invited her to come by and look at the minutes. “Since then I’ve been enthralled.”

Monroe remembered reading the Women’s 20th Century Club minutes at the Beinecke that first day. She followed the rules put in place to protect the materials in the collection, which can be both rare and fragile. After leaving her belongings behind and donning cotton gloves to protect the manuscript from the oils in her fingers, Monroe brought only a paper and pencil into the reading room with her.

Perhaps because she was an unfamiliar face, perhaps for other reasons, a guard stood uncomfortably close to her, watching over her shoulder as she worked. It was a situation that could have easily intimidated her, she said, but she didn’t let it. Instead, she allowed herself to become immersed in what she was reading.

“I wasn’t intimidated because I immediately realized there were 18 women sitting there with me. I wasn’t alone,” she said. “No one in that room knew I was sitting around the table with 18 women and we were having a club meeting.”

By the time Robinson began her performance, the audience had a rich web of context about Wells’ life and times. Robinson entered in a period costume: a blue dress with a high neckline and low hemline, a silver brooch sparkling at the base of her throat. She picked up picture frames as she talked about Wells’ parents and grandparents, then sat at a small table with a newspaper and typewriter as she described how Ida got her start in journalism. The audience followed the emotional beats of her story, laughing or giving an “mmm” of understanding, or of sadness, at just the right times.

Robinson’s play told the story of Wells’ early life and how she discovered her calling as a public speaker. Born before the end of the Civil Car, Wells was orphaned at the age of 14. As the oldest of eight, Wells lied about her age in order to work as a teacher and support the family. Later, she began a career in journalism in Memphis, becoming the first woman in the country to co-own a Black newspaper. When she spoke out about a lynching, Wells had to flee to the North for her safety. Telling her story of survival at Lyric Hall in New York was a major turning point in her activism.

Robinson’s play told the story of Wells’ early life and how she discovered her calling as a public speaker. Born before the end of the Civil Car, Wells was orphaned at the age of 14. As the oldest of eight, Wells lied about her age in order to work as a teacher and support the family. Later, she began a career in journalism in Memphis, becoming the first woman in the country to co-own a Black newspaper. When she spoke out about a lynching, Wells had to flee to the North for her safety. Telling her story of survival at Lyric Hall in New York was a major turning point in her activism.

Robinson portrays both Wells and Phillis Wheatley in her dramatic work, and she aims to develop a new scene each year, chronicling another chapter in the women’s lives. After delving into research, Robinson writes the script; gathers costumes, set pieces and props; and reaches out to other actors to portray supporting characters. She is slowly growing each woman’s story into a full-length play.

Robinson’s artistic journey with Wells began soon after the not guilty verdict was delivered in the Trayvon Martin case, a time when she felt not only heartbroken and angry, but also powerless. She thought about Rodney King, who was killed while she was in college. She thought about Emmett Till, “who was my parents’ generation.” Then she thought about Wells.

“I drew a straight line from Trayvon to Ida B. Wells. I thought, ‘If Ida were alive, she’d have a lot to say about this. We need her today.’”

That sentiment permeated the event. In Wells’ honor, Monroe made space in her presentation for audience members to say the names of Black people killed by police violence and hate crimes. Through the hundreds of lynching cases she documented, Wells was “saying their names” a hundred years ago.

Members of the Women’s 20th Century Club signed a petition in support of an anti-lynching bill that Wells organized, Monroe said. Just this past March, that same bill was finally passed, after 200 attempts and over a century of advocacy.

The 20th Century Club was active into the 1950s, and their political work often took place on the page. In addition to offering community aid, it was a literary organization, with members choosing titles to read together, and presenting literary papers to the group. Much of what they read were “items of the race,” including local Black history on topics like the Amistad case and Prudence Crandall’s school.

Monroe explained that in a world where it was common for Black people to be denigrated in print, literary circles like the Women’s 20th Century Club were central to developing agency.

“This was political. They were not reading for their entertainment. They were reading to know themselves and define themselves,” she said. “These were political acts and they knew it.”

In closing her talk, Monroe reminded the audience of the last lines of Amanda Gorman’s inaugural poem, “The Hill We Climb”:

For there is always light,

if only we’re brave enough to see it

If only we’re brave enough to be it

“The Women’s 20th Century Club members are a beacon for us,” Monroe said. “If we are brave enough, we can be that light for future generations.”

Monroe was certainly doing her part to ensure these women’s light continues to shine. She and Diane Brown, branch manager at the Stetson Branch Library, are beginning preparations to gather the literary works that the club members studied, so that modern-day readers can explore the women’s canon. In addition, Monroe said she is planning to write an article and is working on a play about the New Haven Women’s 20th Century Club. After over a decade of research, it seemed Monroe was bursting with ways to share the work of these remarkable women.

The reason is simple, she said: “They have so much to say.”