Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts | Yale University Art Gallery

| Bix Archer at the talk. Leah Andelsmith Photos. |

The hands and feet tell a story on their own. Light and shadow, line and form, all rendered in charcoal. Details become clear: the foot is twisted the wrong way. The object those hands are holding? It’s a rifle. The adjacent image is neither a hand nor a foot, but a short length of frayed rope knotted around a tree.

These images are part of the upcoming exhibition Reckoning with ‘The Incident’: John Wilson’s Studies for a Lynching Mural, a collaboration between Yale University, Clark Atlanta University, Grinnell College in Iowa, and the University of Maryland. Friday, curators hosted a community conversation titled “Building Dialogue around John Wilson’s ‘The Incident.’” The 20 or so people who attended contributed to the conversation and got a sneak peak of the art.

The exhibition will travel to museums at all four schools, returning to Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG) in January 2020. But more than a year before the exhibition comes back to YUAG, the museum is laying the groundwork for a successful run, starting conversations and presenting context.

Standing next to two compositional studies of “The Incident,” Curator Elisabeth Hodermarsky pointed out how Wilson’s mural (the sketch is pictured above, or featured on YUAG's website here) is conceived in two parts. On one side is a Black family taking shelter in their home: the mother holds the baby while the father stands behind them, rifle in hand. On the other is the grim scene the family is viewing: the lynched body of a Black man recently cut down from a tree.

Klu Klux Klan members crowd in white hoods and robes crowd the body. In between the two sides, there is an ambiguous piece of architecture, a window or the posts of a porch. It may be a “fragile divider not effective in creating safe space for the family,” said Hodermarsky.

| Hodermarsky: “We felt an urgency to bring this work together." |

A drawing of a woman’s face in profile, glowering with rage, appeared to stare at the two compositions Friday. In it, the marks of the charcoal crayon are soft like skin, but they capture the shadows around her eyes and the intensity behind her piercing gaze.

“You can see how he’s working out the position of the head, the lighting,” said Hodermarsky, explaining that the drawing was a study for the father’s expression of simmering fury, though the face belongs to Wilson’s wife Julie, who was white. This blurring of race and gender only adds to the message of the piece, and it’s a prime example of the way this exhibition enriches the viewer’s understanding of the mural and the artist.

Growing up in Boston in the 1920s and 30s, Wilson remembered seeing photos of lynchings almost every day in African-American newspapers like the Chicago Defender. Yale-Smithsonian Art and Social Justice Intern Bix Archer mentioned that while stories of lynchings were common, photos were actually rare.

“But the fact that they dominate his memory shows the impact the images had on him,” she said. Wilson needed an outlet, and he found it in his art.

In the early 1950s, John Wilson travelled to Mexico to join a thriving community of artists expressing social and political messages. That community included other African-American ex-pats wanting to address racism in the United States in their art, like sculptor Elizabeth Catlett and muralist Charles White. Margaret Spillane, Lecturer in English at Yale, explained to the audience what that experience meant to the Massachusetts artist.

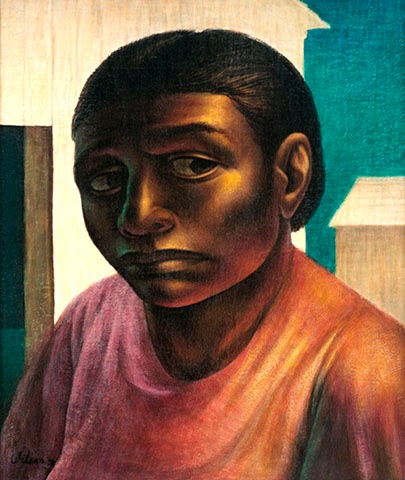

| Left: John Wilson, Negro Woman, study for The Incident, 1952. Oil on Masonite. Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta Annuals. © Estate of John Wilson. Courtesy of Clark Atlanta University Art Collection. Right: The three judges. |

The “Boston brahmins” that dominated the art world in Wilson’s time “did not look at the city they created as a source of art,” said Spillane, who was Wilson’s student when he taught at Boston University. “At BU, form was everything and narrative content was a no-no … people who couldn’t deal with the content of his work dealt with him as a master draftsman.”

It was formative, crucial even, for Wilson to study in Mexico with other artists who had something to say. At La Esmeralda—The National School of Painting, Sculpture and Printmaking in Mexico City—Archer explained that Wilson created his mural “with the understanding that at the end of the semester, the wall would be whitewashed and given to another student,” just as it had been given to him. Fellow muralist and government employee David Alfaro Siqueiros immediately recognized the importance of “The Incident” and was able to have it preserved for a time. But eventually it was painted over and lost for good.

What remains are studies Wilson completed while designing the mural—drawings, oil paintings, and two renderings of the complete composition, as well as several lithographs that are related to the mural, but came after it. They are signs that Wilson spent years working through these themes.

In one of those lithographs, three judges crowd behind a bench. Their faces are distorted like masks, with dark eyes, sharp noses, and lips sternly pressed together. A black man, dwarfed by the bench, stares up at them with tension in his body. A fourth warped face—a woman, perhaps on the witness stand—is elevated like the judges. Though we cannot see his face, the man is the only figure drawn in a natural, fully-human manner. The composition takes the power away from the Black man, but Wilson’s rendering leaves him his dignity.

| John Wilson, Study for The Incident, 1952. Crayon and charcoal. Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College Art Collection, Iowa, Estate of Clinton A. Rehling, class of 1939, by exchange. © Estate of John Wilson. Courtesy Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College Art Collection. |

Archer invited the audience to “do some close-looking” at the studies Wilson made of the mother and child in the mural. The mother sits on a chair, holding her baby in her lap and wrapping her arms around him. Her face tight with feeling, each version casts her emotions in a slightly different light: fear, worry, anger.

Nathalie Miraval, a PhD student in the History of Art and African-American Studies, spoke up with her observations. “In one of the prints, her brow is more furrowed and it’s darker, which is much more expressive,” she said. Then she drew attention to how the mother is not just holding the child, but using her body to shield him or her from the lynching.

Spillane was in agreement: “She has to shield him, but her body is not rigid, so the child won’t cry out while they hide.”

Alexandra Thomas, a PhD student in the History of Art and African-American Studies as well as a K-12 educator at YUAG, offered a bit of historical context from a different angle. Just a few decades after this mural was made, the Reagan era was beginning. With it came the idea of the welfare queen, and “a rise in media that said that an image like this of Black motherhood is not accurate .”

“But there’s a risk because images do wound,” Thomas continued. “Not everyone needs to see these images to start a conversation, because some are experiencing it..” She referenced racially-motivated violence, noting that “there’s a lot of risk in visibility."

YUAG has already been thinking about how to protect viewers, said Hodermarsky. The exhibition will be held in the Rick and Jane Levin Study Gallery, which is tucked away on a mezzanine over the fourth floor and only accessible by elevator and a single, light-filled staircase. An explanation of the show will be posted at each of the two entry points. In other words, “it’s the one gallery you can’t just happen upon,” Hodermarsky said.

On one hand, putting the exhibition in an out-of-the-way gallery feels like hiding it away. But Hodermarsky said the aim is to ensure that viewers are prepared for the strong and sensitive content they will see. The gallery’s small size and cozy nature might aid YUAG in creating her so-called “safe space” for the exhibition. The museum is also considering posting a trauma counsellor in the gallery during opening hours, someone who can help visitors process the exhibit.

Wall text for the exhibition will be minimal. “We don’t want to interpret for people,” Hodermarsky said. The curators also plan to include a life-sized photo of Wilson standing next to his completed mural in Mexico City. Though the photo is black-and-white, it will allow viewers to experience the scale of the work.

The object of the exhibit is to examine one black artist’s reckoning with racism in America, added Hodermarsky. “We felt an urgency to bring this work together,” she said. “In the current social and political climate, with so much aggression against people of color playing out in really horrific ways, we thought this could be a ‘way in’ to address these issues.”

“We’re really happy to have you all in this space today,” she added.

YUAG will host another iteration of “Building Dialogue around John Wilson’s ‘The Incident’” on Thursday Nov. 29, at 5:30 p.m.