Photos Courtesy Yale Summer Cabaret.

m. imani west gestured toward the center of the stage, their limbs stiff, eyes glistening. Distress wracked their body. An unmade bed of all-white linens sat to their left. Aloud, they recounted a letter from an unnamed educational institution and department that claimed to help them.

“They said, you bring a lot of negativity to the room, when I was hurting,” they said. Four piles of clothes–all white–were scattered around them. “And then, you said I didn't ask for help when I cried for it.”

“But the show must go on,” a voice mocked. “You are a vessel.”

Playwright and actor m. imani west set that scene in fuckin loud, which ran at the Yale Cabaret last Thursday through Saturday night (it was originally scheduled to run through July 30; that is no longer the case). Written and performed by west and co-directed by west and Faith Zamblé, the 30-minute performance came through as an experimental, highly visual, visceral and emotional release that followed west’s time at the David Geffen School of Drama.

Photos Courtesy Yale Summer Cabaret.

west later said they plan to continue working on the show as they move beyond New Haven and on to new projects. It is the second of three plays and one film festival in the Cabaret’s summer 2022 season, all dedicated to the work of Black and queer playwrights. Tickets and more information are available here.

At its core, fuckin loud is an efficient and direct work in progress summed up by its three-line poetic synopsis: “i got / alotta shit / to get outta my head.” Like Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf, west’ poetic script is lowercase with unconventional spellings of words. Sprawling, often spare and poetic writing fills the space in between.

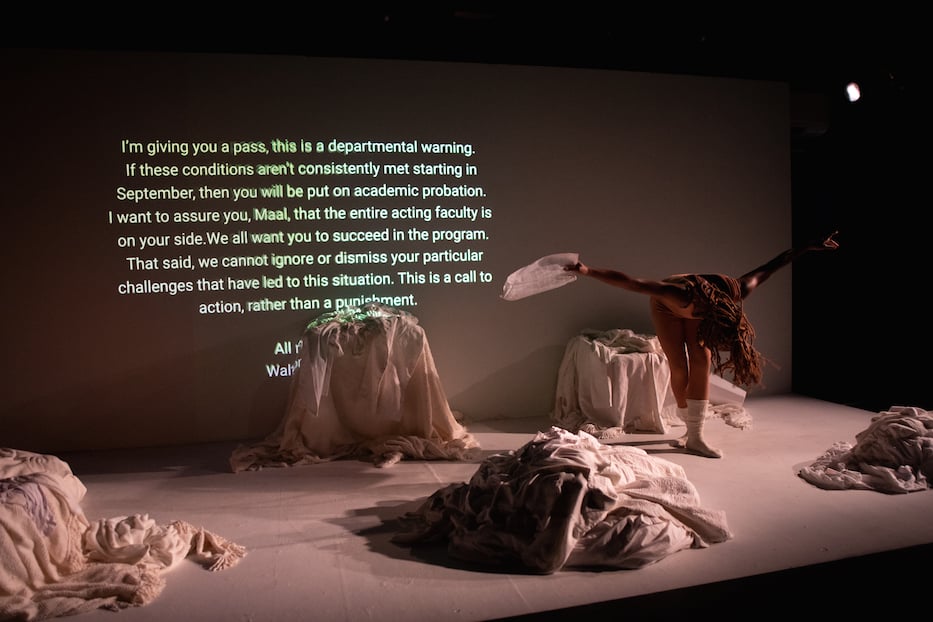

The play begins with a simple catalyst: a typed, multi-paragraph note in sans serif font that west receives from academic leadership. The institution is not named, but in the Cab’s Park Street theater, on Yale University’s neo gothic and heavily-endowed campus, with graduate performers from a school renamed after a billionaire, audience members can venture a guess.

“Your teachers are very concerned about you,” it reads. “They worry about your physical health and the amount of discomfort your body has been in … We’re also concerned about your emotional health and how that seems to affect your ability to partner with the faculty in your training and collaborate with other members of your cohort.”

Photos Courtesy Yale Summer Cabaret.

Photos Courtesy Yale Summer Cabaret.

Last week, the words were projected on the back wall of the Cab’s Park Street blackbox theater, laying bare the propulsive and unsettling force behind the play. As the words appeared, m. clutched the printed note in their quivering hands, while a robotic, artificial intelligence-esque voice read the note aloud over the speakers. Its tone was flat and cold.

west absorbed this information and began to pace the stage (designed by Anna Grigo), which doubled as both a physical (a bedroom) and psychic (the interior space of the character’s mind) setting. A voice boomed over the room, daring them to step beyond their interior hell. When they inched their tube sock-covered feet beyond the boundary, the voice cackled, bellowed, went into a full body mock.

They were trapped, isolated, and physically and mentally alone.

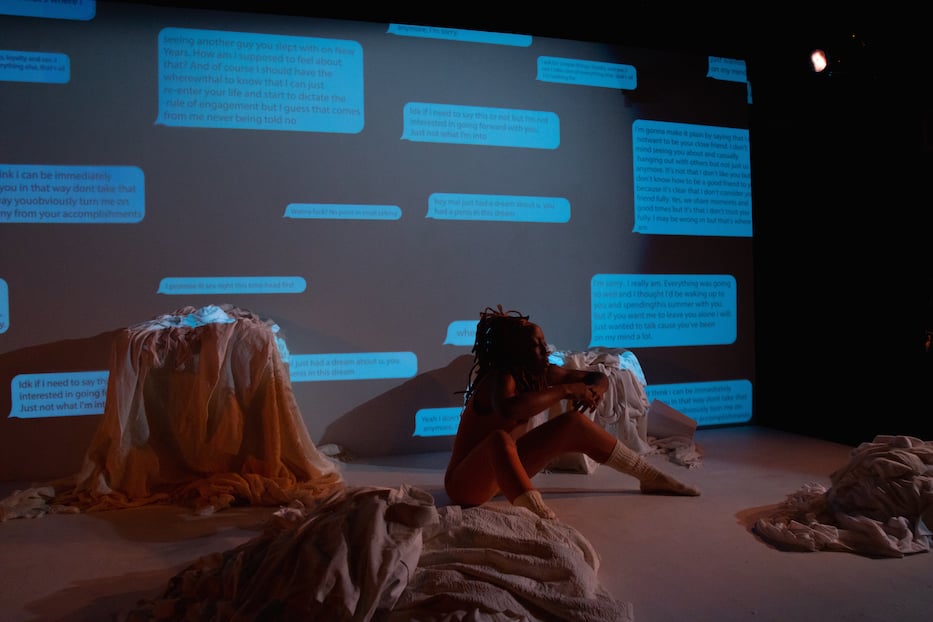

As the play progressed, the interjecting media—skillfully designed by Bailey Trieweiler and his associate designer Stan Mathabane—seemed to increase in severity. Text messages, accompanied by the familiar ding of a phone notification, zipped onto the screen. Voices boomed through speakers. m.'s interior space was flooded with noise—and was, indeed, fucking loud.

Photos Courtesy Yale Summer Cabaret.

Photos Courtesy Yale Summer Cabaret.

The narrative structure worked. With the absence of other characters, the performance rested on west’s shoulders, and they conveyed their experiences through expressive gestures and physical performance (Dava Huesca directed movement). They paced around the room, the tears coming. They tossed themselves across the space and landed on their bed. They shouted, moaned, and expelled air. At the climax, they began a poetic monologue.

“I gonna find good love,” they said at one point. “And I want it to find me and then find me again. In everything. In every form.”

This was their main tool of salvation; working through their obstacles, limitations, desires, and dreams with an audience taking it all in. Trapped in this black box theater, viewers just inches from the fourth wall of their bedroom, they got to tell their story.

Emotional, poetic, and daring in its New Havaen debut, fukin loud came across as a first-person reckoning of a Black, nonbinary character’s survival of and in educational institutions that weren’t made to hold people like them. Rather than drape itself in plot, a cast of physically present characters, or a three-act structure, it privileged the protagonist’s embodied experience.

west has, in this sense, very much succeeded: the protagonist’s unhinging was visually and physically evident and devastating. By the end of the short play, west’s corporeal-focused approach left the viewer physically shaken.

Learn more about the Yale Summer Cabaret here, or call the box office at (203) 432-0863.