Khamani Harrison, who arrived with literature from Hartford's Key Bookstore. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

The high ceilings at the Bradley Street Bicycle Co-Op could barely contain the pulsing of energy of the New Haven Zine Fair. Chatter and music from the Co-Op’s speaker system reverberated throughout the space. Attendees wove through the densely packed room, paging through zines and talking to the people who had created them. Over a dozen different zine displays filled the repurposed garage.

It was a high turnout for the New Haven Zine Fair, which gave “zinesters” (zine sellers) the opportunity to share their identities and connect with others through their printed material. The six-hour event brought in over six dozen people. The idea for the event came from founders of the young zine Connectic*nt, in collaboration with the New Haven-based Bridge and Tunnel Crowd.

“Something I grew up hearing a lot is ‘Connecticut has no culture, Connecticut is really boring,’” said Iyanna Crockett, a University of Connecticut grad who works on Connectic*nt. I think there’s a lot of cool people in Connecticut. It’s just like, there’s no place to convene, and now we’re trying to build that.”

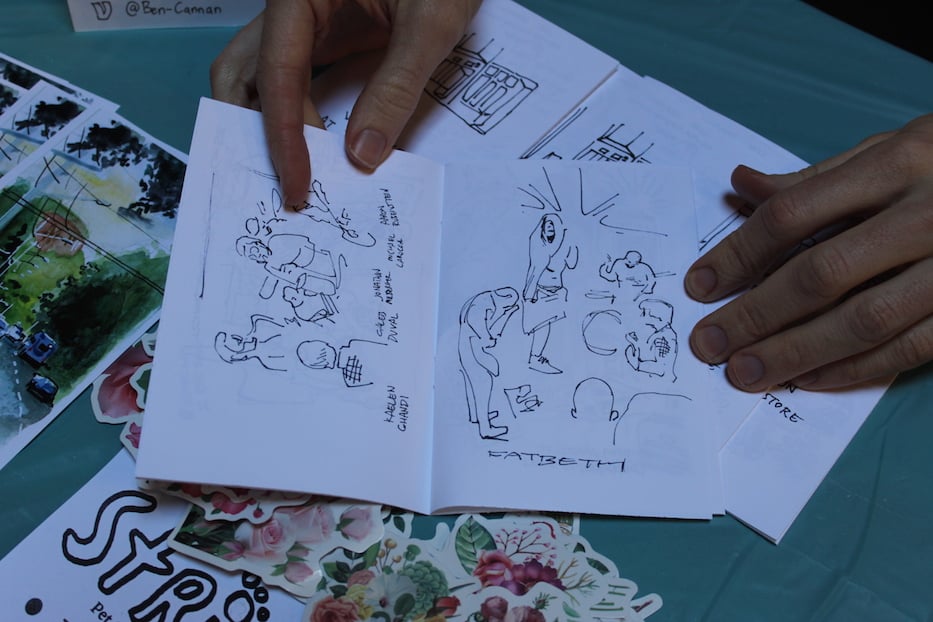

Top: Mar Pelaez and Iyanna Crockett of Connectic*nt. Bottom: Ben Cannan's zine, which he described as a love letter to Never-Ending Books in New Haven. It features live drawings of various music performances that have taken place in the bookstore. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

A zine is the term for a self-published magazine. While the first zine came about in the 1930s, zine culture hit peak popularity in the 1980s and 1990s in conjunction with punk and riot grrrl culture. Zines allow people to share their thoughts and ideas with others in a direct, community-oriented way, circumventing mainstream publishing and barriers to circulation.

Each of the zinesters at the fair were selling work that represented different identities and causes, carving out space for themselves and their communities to occupy.

Connectic*nt, for instance, has had a quick rise to success since its founder Zoe Jensen printed the first copies in Best Printing USA in Norwalk seven months ago. In every issue (there have been five so far), she’s worked closely with Crockett and Mar Pelaez. All three are current or former students at University of Connecticut.

Issue Five of the zine, for instance, celebrates Valentine’s Day. A person with an auburn mullet, bright red tights, and triple-platform adorns the cover. Their limbs are tangled around a large plush teddy bear, and they hold a lollypop to their lips. Their steady gaze at the reader–coupled with their provocative fashion choices– rebuffs the male gaze, creating a space for non-cis male readers.

Olivia Montoya and a customer. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

In a kaleidoscopic array of colors was the North Canaan-based Olivia Montoya’s spread. Montoya displayed over 35 individually packaged zines, many of which were roughly the size of a drink coaster.

The star of the show was her perzine--personal zine--called (meta)paradox, which is about the various identities she inhabits, including queer, disabled, neurodivergent, and mixed-race Latina. Before she discovered zine culture in 2014, at age 22, Montoya didn’t have a platform to discuss the topics that matter most to her.

“Zine culture is a great antidote to society’s message that you don’t have anything important to say or you haven’t done anything important enough to warrant writing yourself,” Montoya mused. “That’s ridiculous—everyone has something important to say.”

Besides giving her a platform to express her various identities, making perzines has an added benefit: emotional release.

“[Making a perzine is] like letting a stranger read your diary. It’s like how I process a lot of things—I write it for a zine and let anyone read it,” Montoya said, chuckling.

%20and%20customer.jpg?width=933&name=Aly%20Maderson%20Quinlog%20(of%20Magik%20Press)%20and%20customer.jpg)

Top: Aly Maderson Quinlog (of Magik Press) and a customer. Bottom: Olivia Montoya's zine display. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

Top: Aly Maderson Quinlog (of Magik Press) and a customer. Bottom: Olivia Montoya's zine display. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

The now 30-year-old Montoya is dedicated to teaching others how to make zines. She’s been doing so through her Let’s Make a Zine which, to maximize accessibility, she sells at the price of printing and also has made available on her website for free. To further Connecticut zine culture, in 2019, she organized the first-ever zine fair in Lichfield County.

One of the people her zine teaching has reached is her mother Connie Boje, who was stationed next to Montoya selling her own zines out of a carry-on-size rolling suitcase. The influence of Montoya was evident in Boje’s packaging; Boje’s zines were also “quarter-size” and packaged in plastic baggies. For Boje, a poet, making zines has been a way to distribute her poetry to wide audiences.

Stationed at a table by the door was the Vermont-based Katherine Leung. Arrayed before her were the fruits of two years of labor: dozens of copies of her arts zine Canto Cutie, of which she has published four issues so far. Each copy is professionally bound and contains 150 full-color pages and writing in both English and Cantonese.

Canto Cutie display. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

The zine exterior is dandelion yellow and in light magenta is the pointillist ink drawing, by Daisy Chan, of a woman holding a hand-sized mirror in the circle of her palm. Reflected back onto the viewer is the image the woman sees as she looks into the mirror: her eye, her mouth, and an expression of radiant calm.

That it seems to call out to the viewer “you see me, and I see you” encapsulates what Leung hopes to accomplish with her zine project: allowing people of common backgrounds to recognize and connect with one another across vast physical distances.

Like (meta)paradox, Leung created Canto Cutie to fill a lack. In 2020 she was living in the Bay Area, where as a Cantonese American she was an ethnic majority. Still, there was no publication that catered towards bilingual Cantonese and English speakers from the Cantonese diaspora about art. Her latest issue, issue 4, showcases work from Cantonese artists across the diaspora—including in Portugal, San Francisco, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Now based in Vermont, where her Cantonese community has shrunk, Leung has kept up her zine—and it has grown in size. She prints 200 copies per issue, which she sells on her e-commerce website. 1,400 people follow the Canto Cutie profile on Instagram.

“I continue this work because it’s necessary and it’s important to educate people about my identity,” she said.