Arts & Culture | Public Health | History | COVID-19

| All images from Connecticut Historical Society. |

International conflict and contentious borders. Civil unrest and mask wars. Polarized politics, and global pandemonium. The year is not 2020, but 1918.

Friday afternoon, participants joined the Connecticut Historical Society (CHS) for its weekly Coffee Hour. The online series comes in response to COVID-19 closures—CHS will bar its own facilities through Aug. 18. The organization still seeks to educate Connecticut residents about their history in the face of quarantine isolation, from The Amistad Slave Rebellion to the filmography of Katharine Hepburn.

Friday's installment, dubbed "Coffee Hour | The Flu Pandemic of 1918," was no exception. CHS Museum educators dissected the past pandemic through presentation and discussion. Participants attended sessions in smaller Zoom breakout rooms, enabling more intimate conversations throughout the featured presentation. Museum Educators Taylor McClure and Annie O' Brien headed a group of 37 attendees Friday.

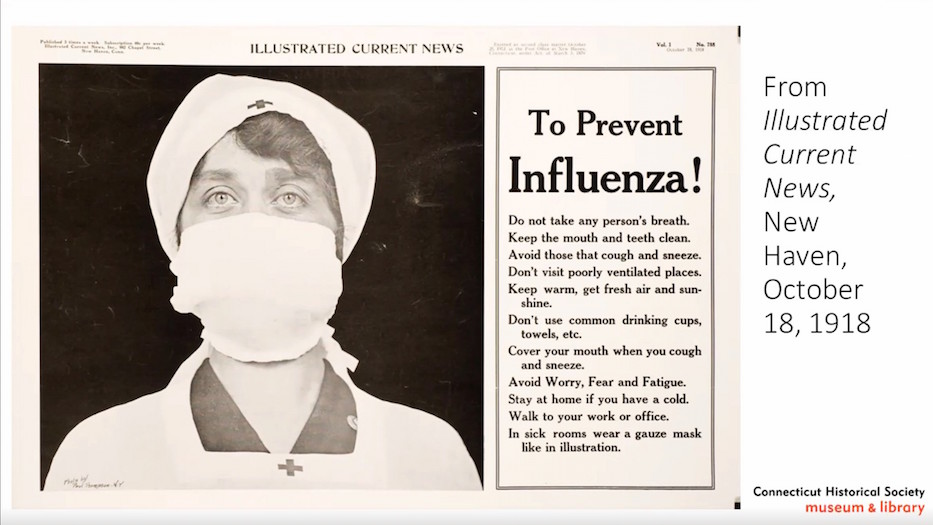

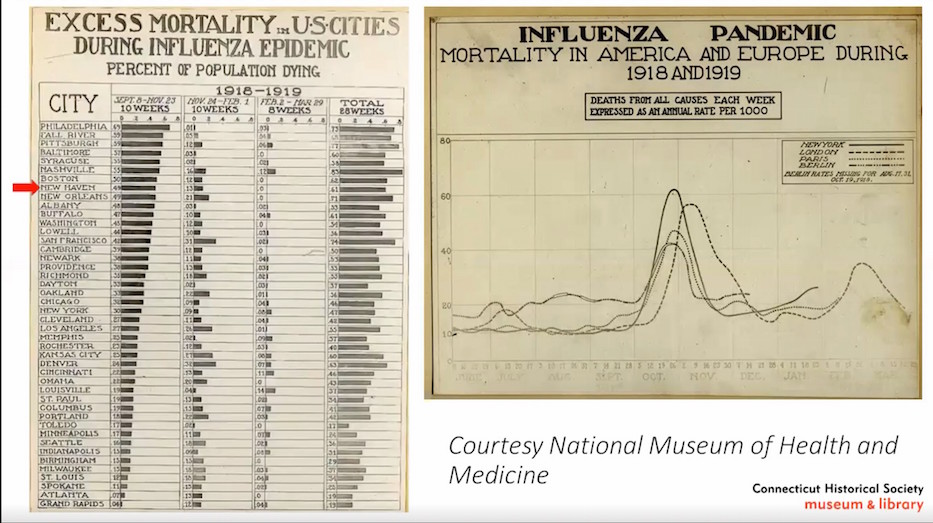

"The 1918 flu killed between 50 to 100 million people worldwide—more than the military deaths of World War I (WWI) and World War II (WWII) combined," McClure began. "It caused the average life expectancy in the United States to drop by 12 years for both men and women. By the end of 1918 alone, more than 675,000 Americans died of influenza—the equivalent of 2.16 million Americans dying today."

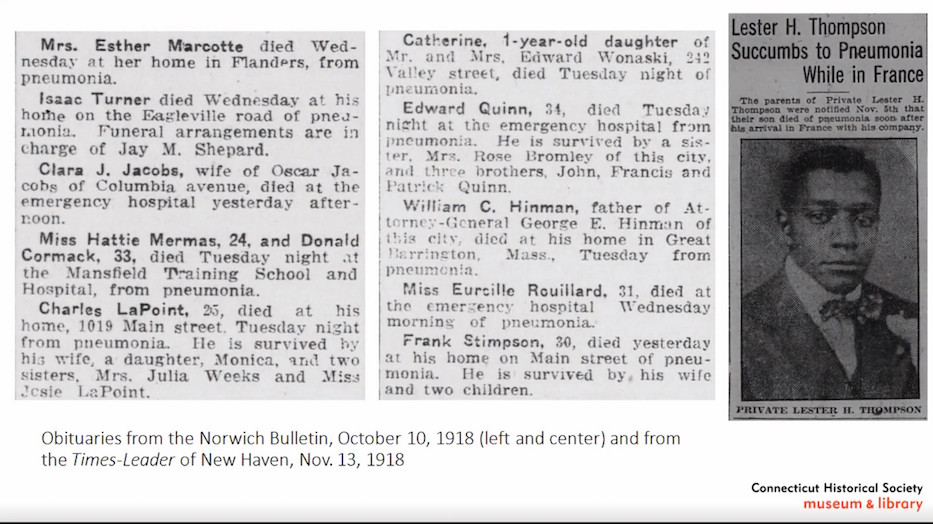

The 1918 pandemic lasted a "hellish two years" between the springs of 1918 and 1920, she added. The strain manifested from a violent mutation in the H1N1 influenza virus genome, spreading rapidly amongst the global population. The typical flu virus' most vulnerable hosts are the very young and old, or the immunosuppressed. Instead, 1918's novel contagion ravaged young adults' respiratory systems. Its average victim was 28 years old.

The medical field's limited understanding of germ theory left it woefully unprepared for a disease with no identifiable bacterium. Antibiotics to counter secondary infections wouldn't come for more than a decade. Men were off to war, children were orphaned, the economy was in recession, and racial insurrection was commonplace —1918's fear and uncertainty set the world at a standstill.

The description was chillingly familiar for many of the Zoom's participants, historic recurrence setting the conversation's tone.

"It's hard not to make comparisons between the 1918 pandemic and what's happening now," McClure said. ”Especially as we go through how people respond. Remember, regardless of time, denial is a very, very powerful thing."

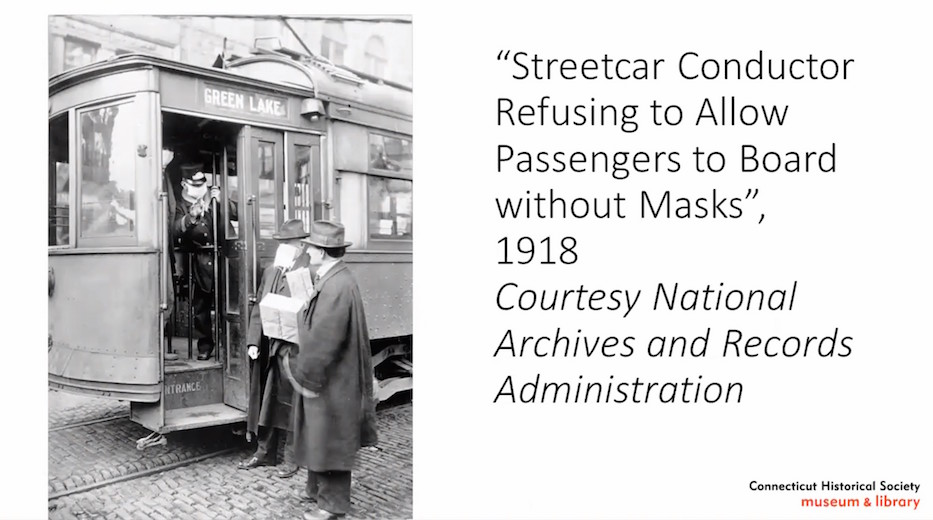

Denial took many forms during the 1918 pandemic, first in the form of xenophobia. The Flu Pandemic of 1918 was—and currently is—colloquially referred to as the "Spanish Flu" or "Spanish Lady." The slur echoes uses of "Kung Flu,” “Wuhan Virus,” and "Chinese virus" from the current administration and its supporters. Ire toward the Iberian Peninsula's citizens stemmed from misinformation. McClure noted censorship's proliferation throughout the war effort—anything denouncing WWI or lowering morale was treasonous in most nations.

Spain's neutral position in WWI granted it freedom of the press, unlike its warring counterparts. When Spain’s King Alfonso XIII fell ill, Spanish newspapers rushed to report on the destructive disease. Americans blamed the Spaniards. Ironically, historians pinpointed the virus' origin to Haskell County, Kansas.

Distaste for the Spanish grew into hatred of all European immigrants. As marginalized groups today, immigrants in 1918 were disproportionally affected by the pandemic. Rampant discrimination made it nearly impossible to gain access to medical care and secure safe housing. Immigrants were forced into squalid living conditions in crime-ridden areas. Most fell into the virus' most vulnerable age group.

Denial trudged on, digging its heels in both the home front and battlefield. Most downplayed the illness' severity. The president's assurances that the novel coronavirus will "go away," "sort of disappear," or "vanish within a couple of days" mirror 1918 national sentiments—President Woodrow Wilson, a victim of the 1918 flu, refused to acknowledge its existence in public. Today, the current occupant of the White House long denied the importance of masks and shelter-in-place orders to stem the spread of COVID-19.

Production slowed across the United States as workers collapsed from fever. Generals told their soldiers to "gargle saltwater" against a "little cold." Units were dying in droves. It was a common belief that sufferers could "will themselves better" by being joyful. A Connecticut Red Cross nurse described having the H1N1 virus as a "lovely time." To keep spirits up, the government encouraged citizens to go to the movie theatre and laugh with friends and family.

1918 Naval Nurse Josie Brown painted a much more disturbing picture many years after her service, not unlike doctors at some New York, Florida, and Arizona hospitals have done in the past four months.

“The morgues were packed almost to the ceiling with bodies stacked one on top of another. The morticians worked day and night. You could never turn around without seeing a big red truck loaded with caskets for the train station so that bodies could be sent home. We didn't have time to treat them. We didn't take temperatures. We didn't even have time to take blood pressure. We would give them a little hot whiskey toddy— that's about all we had time to do. They would have terrific nose bleeds with it—sometimes, the blood would just shoot across the room, and you had to get out of the way, or someone's nose would bleed all over you.”

As the severity of the pandemic grew, civilians turned to sham remedies in desperation. Some downed alcohol in copious amounts (the American Heart Association has recently released new warnings about excessive alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic). Others clung to newspapers, spreading misinformation and mass hysteria. Ads reported that "a few smokes" cleared the nasal passages, and "malted milk" would chase the virus out. Tastes have become more refined in the modern age— "injecting disinfectant" and unregulated "hydroxychloroquine use" are our snake oil.

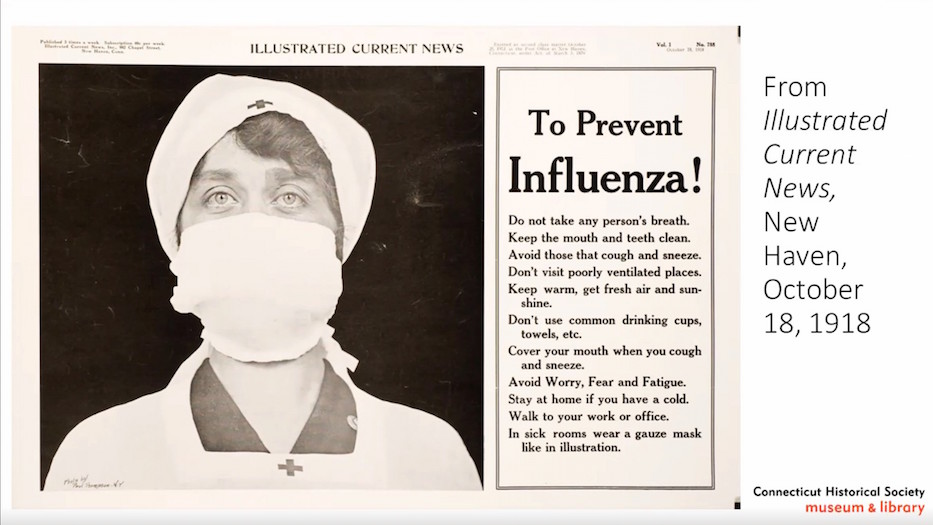

By the end of 1918, masks were mandatory, and state governments enforced widespread closures:

"Say, Frank," wrote a citizen in a letter. "This is some town—no place to go. Did you know that the town is locked up? Yes, movies, leading schools, and even churches on account of the influenza. It is in the paper that Father Crowley is going to have masses in the schoolyard—the place will be closed for two weeks."

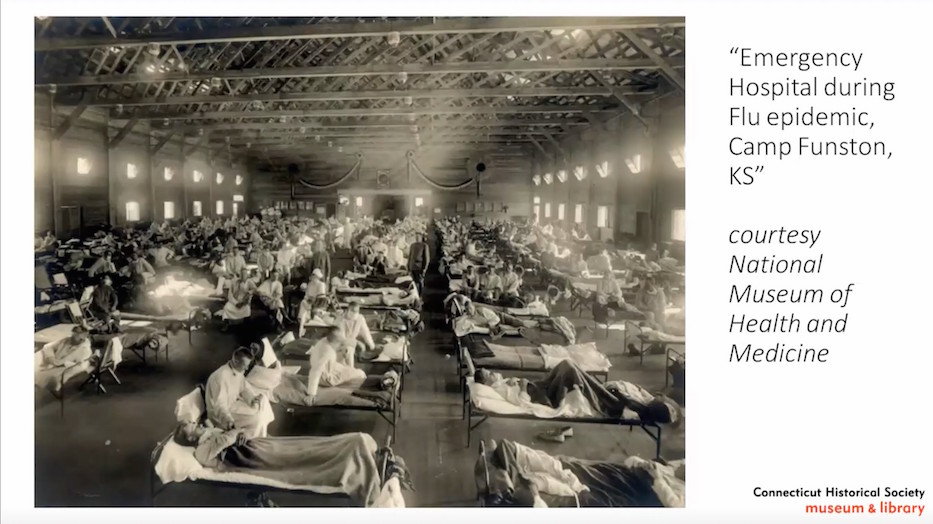

Even with limited medical knowledge, doctors insisted that residents avoid crowds and wear masks to prevent the transmission of respiratory droplets—Americans in 1918 (and 2020) found both rather difficult. Some became outraged when denied access to public transportation because they wore no masks. Others would poke holes in their masks to get "fresh air" or to smoke.

Officials encouraged citizens to rally against such slackers. Stylish women deemed masks unfashionable, instead wearing a veil of cheap gauze off their hats' brim. The smallest offenders wore their masks under their noses.

A November 1918 edition of The San Francisco Chronicle noted citizens ire towards the masks the government "idiotically forced them to wear." It documents citizens ripping the coverings off and throwing them in the air to celebrate Armistice Day.

"It's distressing from our perspective today to see that a lot of the way that it was transmitted could have been preventable or treatable,” McClure noted.

“Still, there's quite a bit to learn from if we can document these times," she added as the discussion came to a close. "We are actually asking people to document and collect memories of our current situation because this is such a life-changing event. That's something that we are asking for through our website if you're interested in documenting different parts of this particular pandemic, we would be grateful for your help."

Want to catch more Coffee Hour? Click here.